Levi Strauss created the first pair1 of blue jeans in 1873. He went to San Francisco to make his money in the gold rush but found more success using denim and rivets to make pants that would last longer. They were actually called waist overalls until 1960 when baby boomers began calling them jeans.

In a world full of innovation and creative destruction it’s impressive the company has lasted as long as it has.

Yesterday the Levi Strauss & Co. went public by raising more than $600 million in an IPO which saw the stock price shoot up 30% or so on the first day of trading. The company is now valued at almost $9 billion. Levi’s was a public company in the 1970s and 1980s until going private in 1985.

CNBC reported the IPO was ten times oversubscribed.

It doesn’t seem to make much sense that IPOs are so often oversubscribed when the research shows they tend to underperform the market over the long haul.

There are plenty of behavioral biases at play when this happens. People prefer lottery-like payouts in hopes they can strike it rich. Everyone has heard stories of people investing money in the IPOs of Apple, Microsoft or Amazon and striking it rich.

But this also has to do with the fact that the majority of the returns for IPOs tend to come on the first day of trading.

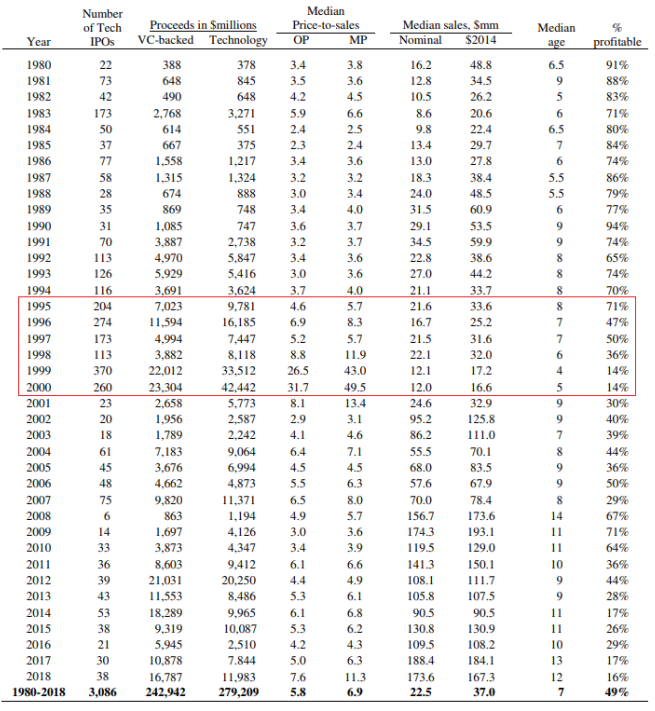

Jay Ritter, a professor at the University of Florida, and an expert on IPOs has a treasure trove of data on initial public offerings that he updates annually on his website.

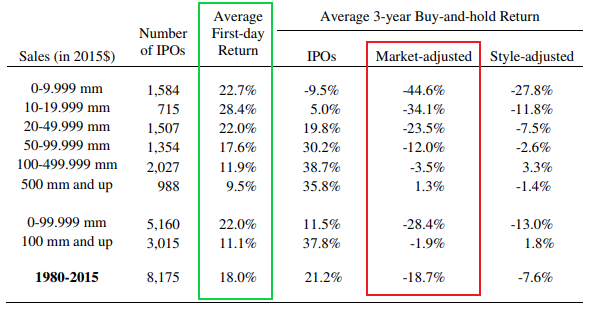

Here you can see the average first-day return for IPOs by different revenue levels from 1980-2015:

The average first-day return is quite large while the average three-year returns tend to lag the market.

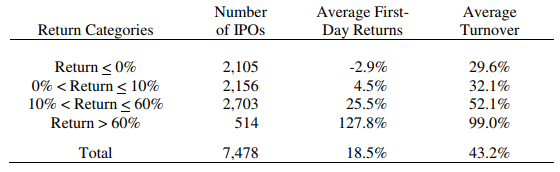

The distribution of those first-day returns is also instructive as to why IPOs tend to be oversubscribed:

More than 36% of IPO names since 1980 have seen a big pop on the first day in the range of 10%-60%. Nearly 7% of the time that first-day return is more than 60% right out of the gate. Returns are positive more than 70% of the time on the first day of the IPO.2

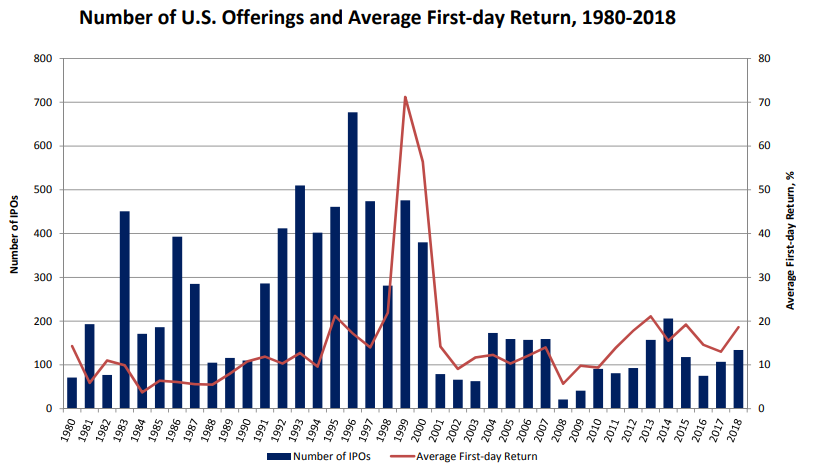

Those average first-day returns may be skewed by the 1990s dot-com bubble:

But it would be impossible for the numbers to not be skewed by the dot-com bubble. Just look at how many IPOs there were:

People worry about the fact that the number of public companies in the U.S. has fallen by about half since 1997 (from roughly 7,000 to 3,400) but the 1990s is more of an outlier than today.

There may be a ton of irrational investors scratching and clawing for shares of new IPOs like Levi Strauss (and just wait for the Lyft and Uber offerings later this year). But there also may be plenty of investors who are simply hoping to get a piece of a first-day bounce and flip it for a quick profit.

So buying shares of an IPO could be rational or irrational depending on your time horizon…and how lucky you are with what happens on the first day of trading.

Further Reading:

Supply & Demand in the Stock Market

Now here’s what I’ve been reading:

- How to sidestep lifestyle creep (Betterment)

- The investor’s cheat sheet (Bps & Pieces)

- What happens to funds after you sell them (Morningstar)

- Why the 4% rule doesn’t work (Monevator)

- The phantom gambler (Paris Review)

- How to blow it (Humble Dollar)

- Is your home an investment? (Abnormal Returns)

1I’ll never understand why it’s called a pair of pants. It’s one pant with two legs.

2Which makes sense from a career risk perspective for the investment banks. Some people think they’re leaving money on the table but they like to see big up days on the initial trading day.