There a plenty of topics that seem to get investors all worked up — active vs. passive, individual bonds vs. bond funds, and of course, shareholder buybacks. Depending on who you ask, buybacks are either a signal that capitalism has gone too far or the greatest thing to ever happen to investors. As with most debates, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. This piece I wrote for Bloomberg puts the buyback debate into perspective to help understand how these things really work. The U.S. senator I wrote about in this piece even gave a response after seeing this one (see my follow-up here).

*******

Share buybacks are a hotly debated topic during this economic expansion and bull market. Many are worried that the Republican tax cuts will further exacerbate growing wealth inequality, particularly as the majority of the benefits will be returned to shareholders in the form of increased stock repurchases.

This has led Democrats in Congress to introduce a bill that would prohibit corporations from buying back their own shares. Senator Tammy Baldwin, the Wisconsin Democrat who introduced the bill, said, “The very partisan corporate tax bill has fueled a surge in stock buybacks that is hurting economic growth and shared prosperity for workers.”

This line of thinking misrepresents how share buybacks work and the impact they have on the stock market. You would never hear politicians complain about corporations paying out dividends but, in many ways, share buybacks are simply dividends in disguise. When dividends are paid out, investors are receiving their share of corporate profits in the form of a cash payment.

The idea behind share buybacks is that by eliminating the number of shares available on the open market, the remaining investors will earn a larger piece of corporate profits. Buybacks are simply increasing the amount of profits per share available to the investor.1 With dividends, investors are able to allocate cash flows as they see fit but those payouts are also subject to double taxation. 2 Because investors can always create their own dividends by selling shares, they should generally not care whether a company decides to pay a dividend or buy back its own shares.

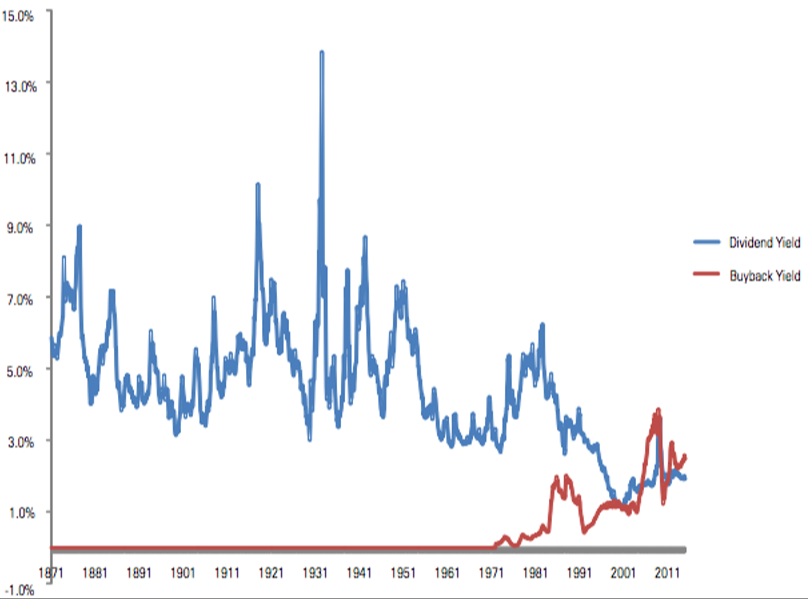

Before the early 1980s, share buybacks were rarely used by corporations. Dividends were the main tool for returning money to shareholders. Then in 1982, the Securities and Exchange Commission created rules that made it easier for corporations to buy back their own shares without the fear that they would be subject to regulations that would charge them with manipulating their own stock price. A study from Roger Ibbotson and Philip Straehl showed that this really opened up the floodgates for buybacks:

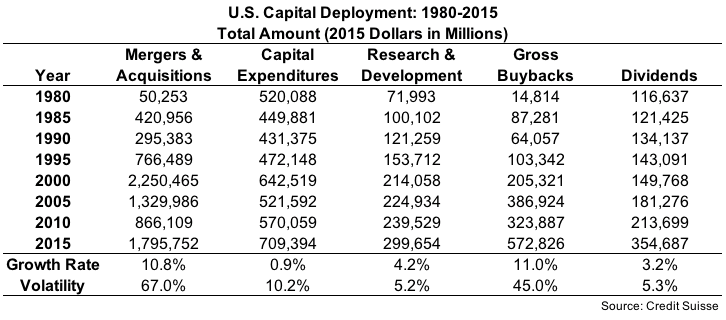

This graph shows the historical dividend and share buyback yields going back to the late 1800s. Dividend yields have fallen dramatically in this period, but buyback yields had huge gains after being nonexistent for the majority of the market’s history. Still, there are other options when it comes capital allocation decisions made by corporate management that can have an impact beyond dividends and buybacks. Capital can also be used to invest in future projects, research and development or mergers and acquisitions. If you look at the data, M&A activity dwarfs both buybacks and dividends, as do capital expenditures. Research from Credit Suisse shows the growth or each of these categories going back to 1980:

Dividends, R&D and capital expenditures are much more stable over time, while M&A activity and share repurchases tend to be more cyclical and volatile in nature. Most critics of share buybacks would prefer to see corporations invest more for the future of their business rather than repurchasing their own shares in the market. This would seem to make sense on the surface but the stock market provides a high hurdle rate in terms of assessing capital allocation decisions.

In a basic sense, the capital allocators have two choices about where to deploy their cash — return money to shareholders or make investments in their assets or technology for the future. The research shows that companies that buy back their shares actually outperform companies that have a higher share of investment for the future. On average, firms that invest a higher proportion of their capital underperform firms that invest a lower proportion. The companies that invest more underperform those that invest less, on average, by nearly 0.5 percent per month.

So for every Amazon that is successful in its long-term investment initiatives there are far more corporations that don’t earn high returns on their internal investments. In most cases, CEOs would see better stock performance by returning capital to their investors. The stock market is hard to beat over the long term.

If Congress really wants to help working Americans, lawmakers should encourage more people to invest in the stock market to take advantage of corporations returning money to shareholders, whether that’s in the form of buybacks, dividends or any other number of capital-allocation decisions. The stock market remains the easiest way for individuals of all shapes and sizes to earn a piece of corporate profits and take advantage of technological advances and innovation.

There are companies that only issue share buybacks to avoid diluting shareholders because of stock options granted to management, but the net number of buybacks of the entire market tends to benefit investors overall.

At the corporate and individual investor levels.

Originally published on Bloomberg View in 2018. Reprinted with permission. The opinions expressed are those of the author.