Capital allocation is one of the most important decisions management has to make for corporations. Changes in regulations have made it more important over the years for investors to pay attention to not only dividend yields, but also share buybacks, debt repayment and M&A. This piece I wrote for Bloomberg goes over how things have changed in recent decades in capital allocation decisions and what it means for shareholder yields.

*******

One of the reasons many investors are forecasting lower returns in the stock market is simply that dividend yields are much lower than they have been historically.

The expected returns formula for the stock market looks something like this:

Expected Stock Market Returns = Dividend Yield + Earnings Growth +/- Change in P/E Ratio

Earnings growth and the change in price/earnings ratio are tough to pin down because one depends on how profitable corporations are in the future while the other boils down to how much investors are willing to pay for stocks at any given point in time. But the other component is very straightforward. Dividends yields are a known commodity.

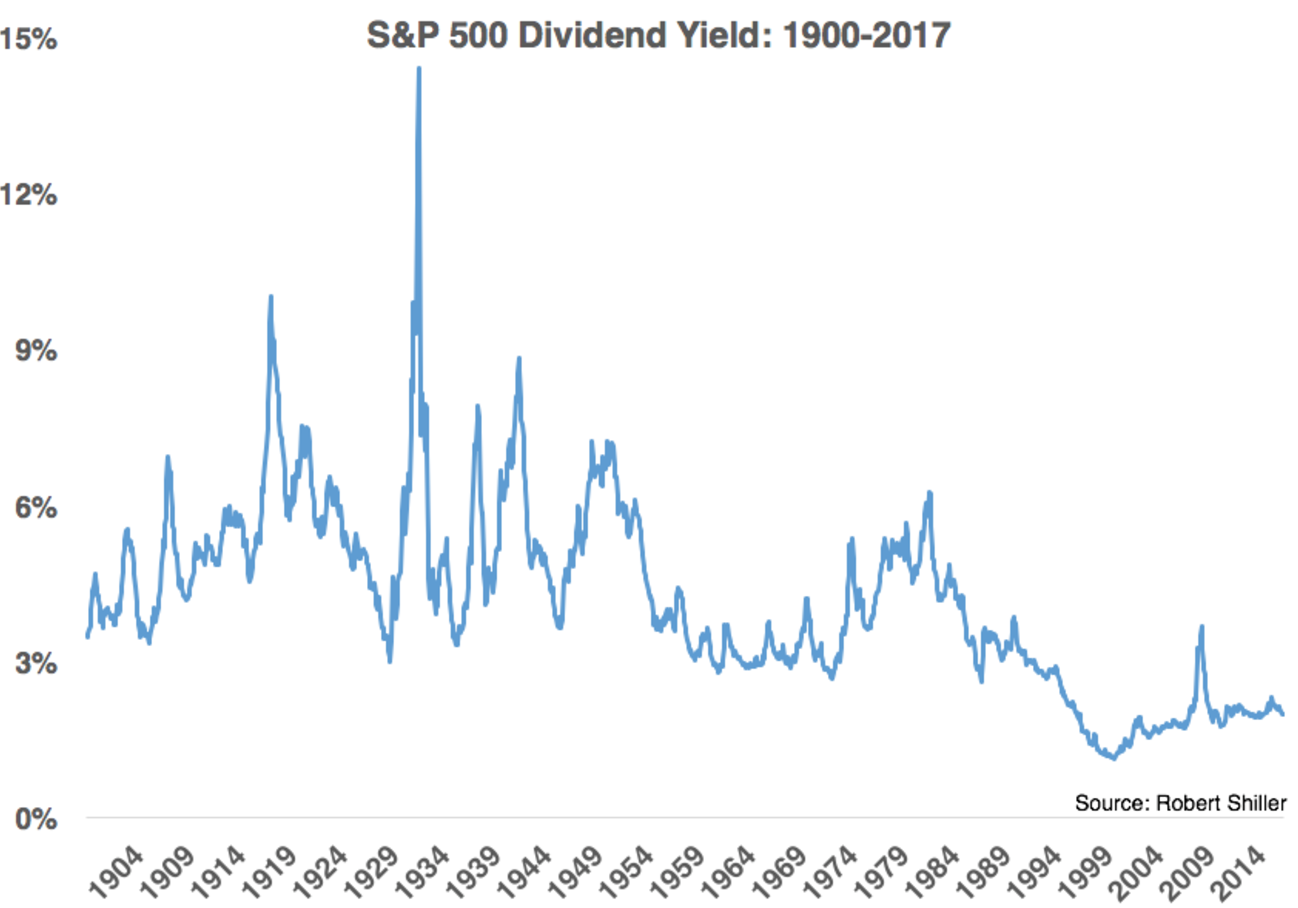

Here is the dividend yield on the S&P 500 going back to 1900:

Over this period the average dividend yield was almost 4.2 percent. The current 2 percent yield pales in comparison.

So do these lower dividend yields mean lower future returns for stocks?

Not necessarily. Investors need to look beyond simple income numbers when thinking about how much their stocks yield these days.

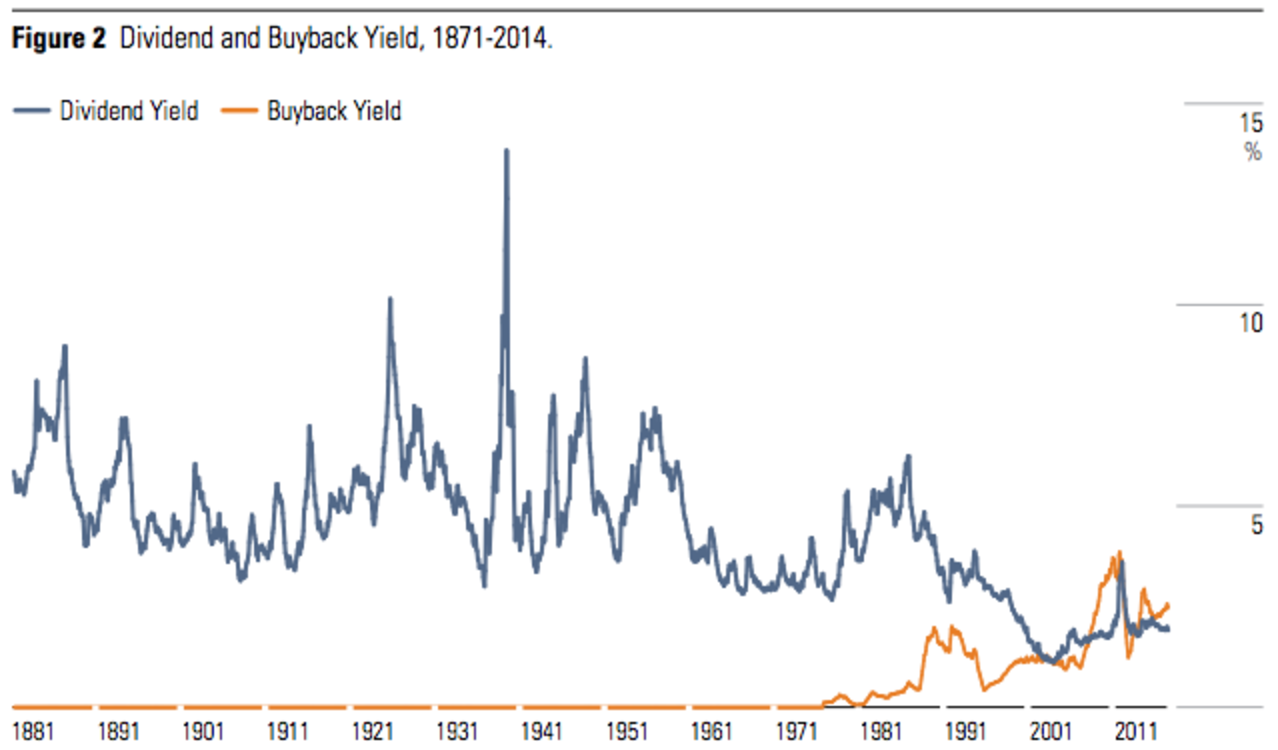

The reason stocks have gained so much during the current bull market has a lot to do with the lower yields. But that doesn’t tell the whole story. In the early 1980s, the Securities and Exchange Commission instituted a new regulation that gave corporations incentives to repurchase their own shares. Before then, it was much easier for companies to simply distribute cash back to shareholders via dividends.

This has completely changed how chief executives allocate capital. The researchers Roger Ibbotson and Philip Straehl looked back at how this relationship has affected market yields. The following graph shows how share buybacks took off during the 1980s and now account for a larger proportion of overall yield than dividends:

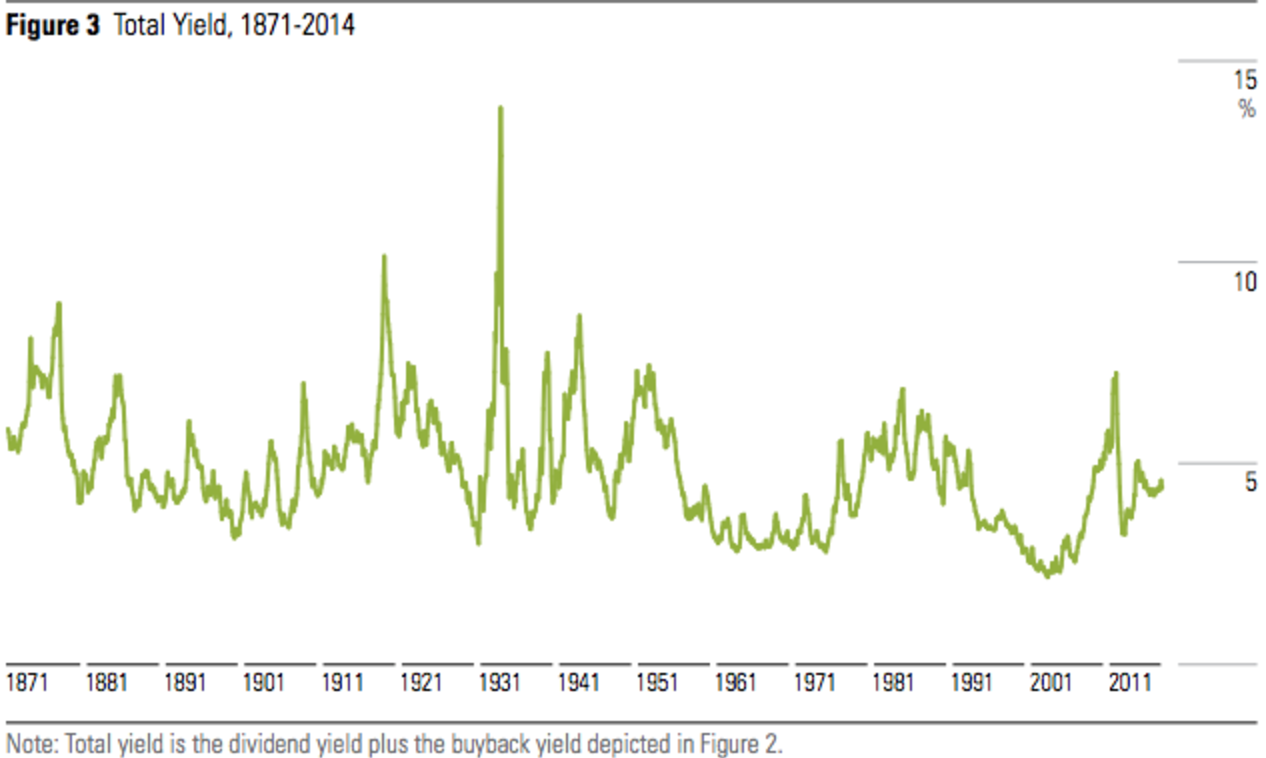

Combining the dividend yield and the buyback yield gives us total shareholder yield. And if you look at things from the latter’s perspective, today’s yields don’t look quite as poor as many investors assume:

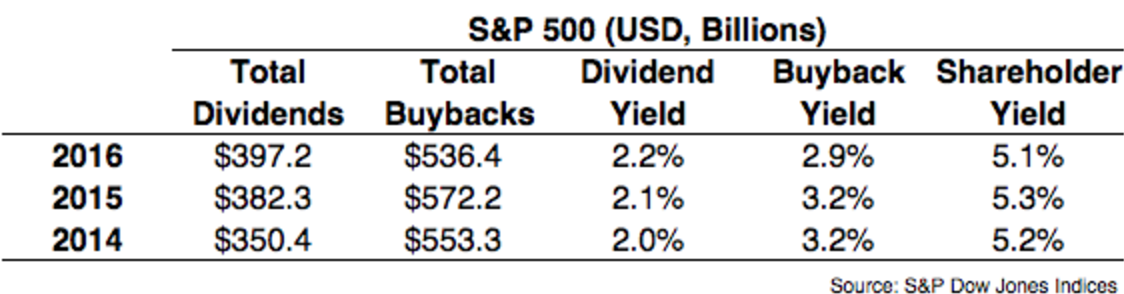

Ibbotson and Straehl’s study only goes through 2014, but Howard Silverblatt from S&P Dow Jones Indices recently updated this data through the end of 2016:

Much like the performance of the market itself, the number of share buybacks is concentrated in the largest names in the index. Silverblatt noted in his report that the top 20 companies in terms of buybacks accounted for almost 50 percent of total expenditures. Aided by the huge buyback program from Apple, information technology as an industry has repurchased more than $622 billion in stock over the past five years, well over $220 billion more than the next highest spending sector, consumer discretionary.

From the end of 2012 through the end of 2016, total dividends and share buybacks on the S&P 500 are up 42 percent and 35 percent, respectively. These numbers haven’t kept up with the almost 70 percent total return on the stock market in this time, but there are cash flows backing up this rally.

Investors have a strong attachment to dividends because that income in the form of cash flow can feel comforting when it shows up on a regular basis. But from a total return perspective, investors should be indifferent to the capital allocation decision between dividends and share buybacks. 2 In the grand scheme of things, buybacks and dividends are basically identical to the end investor. With dividends, investors are receiving their share of earnings from the company. With buybacks, they are also receiving their share of earnings from the company but it’s just coming from an increase in earnings per share.

Investors can create their own dividends by simply selling shares in stocks that have increased in value from higher earnings results.

In recent years there have been a lot of headlines about how share buybacks have been propping up the stock market. You never see the same headlines talk about how dividends are propping up the market, but they achieve the same result. Both dividends and share buybacks are indications that corporations are seeing an uptick in fundamentals through an increase in cash flows. While it’s true that dividends and buybacks are often funded through borrowed funds, the fact that the yield has remained relatively stable in a rising market environment means that there are positive fundamental underpinnings to this market rally.

Shareholder yields are higher than most investors appreciate but that doesn’t mean they can keep the market rising forever. In 2016, total outlays to dividends and buybacks declined by more than 2 percent. Investors could certainly decide they no longer wish to grant the market a premium P/E ratio if interest rates were to rise substantially or CEOs were to continue cutting back the amount of money they’re returning to shareholders.

Originally published on Bloomberg View in 2017. Reprinted with permission. The opinions expressed are those of the author.