Every year the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) puts out a study on the investment performance of college endowment funds. It’s a comprehensive report that goes through the asset allocations and performance numbers of funds ranging from a few million dollars to funds with many billions of dollars (in the latest report there were over 800 funds in total).

Institutional investors are obsessed peer comparisons so they all eagerly await these performance numbers to see how they stacked up against the competition.

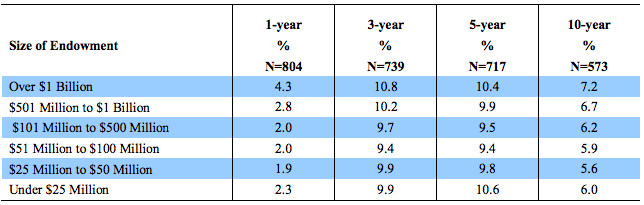

Here’s the latest batch through June 30, 2015:

In the hierarchy of institutional investors you won’t find a more competitive group than college endowments. They’re in constant competition with not only trying to beat the market, but also beat each other. It’s almost like a bizarre finance version of a heated college football or basketball rivalry.

Endowment funds are constantly looking for the best money managers — utilizing both the public and private markets — to find the best investment opportunities. They’re well-staffed and well-educated. They have access to the best and brightest minds in finance and are able to invest in funds that are reserved only for those with many millions of dollars. I decided to see how these endowment funds matched up with one of the simplest, low-cost portfolios out there today — the Vanguard Three Fund Portfolio.

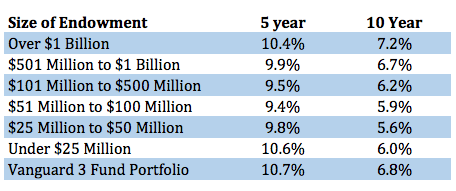

For a total cost of just 0.19% (even less if you used the ETF versions of these mutual funds) you can put together a broadly diversified portfolio the John Bogle way. This portfolio consists of 40% in the Vanguard Total U.S. Stock Market Index Fund, 20% in the Vanguard Total International Stock Market Fund and 40% in the Vanguard Total Bond Market Fund (basically a traditional 60/40 fund). Here’s how the Bogle portfolio stacks up against the endowment funds over the past 5 and 10 years (1 and 3 years returns are mostly noise):

Vanguard beat the average over the past 5 years for every endowment size and came up just shy of the $1 billion and over group over 10 years while besting the rest of the group averages. Think about these results for a minute — these endowment funds hire the biggest investment consultants, have huge investment committees, connections with alumni at some of the best money managers in the world and fully-staffed investment offices in many cases. All that work, all of those due diligence trips, all of those extra fees paid to money managers and the majority of these funds still couldn’t beat a low-cost Vanguard index portfolio that was simply rebalanced once a year.

And that’s not to mention the risk that these funds tend to take in more private, highly levered, illiquid securities and fund structures. The Vanguard funds have full transparency, daily liquidity and employ no leverage, performance fees or lock-ups. It’s a far more operationally efficient portfolio with no headline risk to speak of.

A few thoughts on these numbers and what they may mean:

- It’s becoming harder to outperform. The early adopters in many of the more illiquid alternative asset classes earned a huge first mover advantage in those markets and were paid handsomely as a result. Private equity, real assets and hedge funds are now extremely competitive with a late push from sovereign wealth funds, large pensions and the rest of the endowment and foundation community scouring these markets for investment opportunities. Premiums in these markets have all but vanished save for a handful of the top funds in each category.

- These numbers show the average returns so there were obviously some endowments that outperformed. In the past these outperformers were basically same schools year in and year out. My guess is the competition and copycat nature of the industry means that, while there will still be certain funds that outperform, the roster will likely change from year to year and the amount of outperformance will compress versus historical averages. There’s an old saying that, “nothing fails on Wall Street like success.” The Yale Model may be a victim of its own success.

- Passive investing has had a pretty nice run in the past few years. That could have some bearing on these numbers. Active management has struggled mightily, especially of the hedge fund variety, and endowments have a higher allocation to hedge funds than anyone. It’s possible there could be a reversal of this relationship at some point in the future, but time will tell how long that would last.

- Costs and behavior matter. You don’t always get what you pay for in life and that’s more true in the financial markets than anywhere. The high fees that endowments are willing to pay their alternative money managers had to take a toll eventually. And when many of these funds failed them during the financial crisis, instead of changing course many simply doubled down and invested even more in the space. They lost in both directions.

- These endowments would be much better off if they spent more time focusing on organizational alpha than trying to outperform their peers. A focus on governance — lowering costs, decreasing complexity, making better long-term decisions, documenting their investment process, defining their goals, focusing on asset allocation instead of money manager due diligence, matching their investments with their longer-than-average time horizons and ensuring they have enough liquidity to meet short- and intermediate-term spending needs — would pay better dividends than peer performance reviews.

There’s a ton of ego involved in the college endowment world. No one wants to admit that there’s a much simpler way to be better than average.

Source:

NACUBO Endowment Study

Further Reading:

Goals-Based Investing

Any prediction on whether any big name endowment will ever announce that they are going bare bones, so to speak? If so, how long before it happens? It would seem to me that at some point someone who makes decisions at a high level would analyze performance in the same way you did and and decide “enough is enough.” That would have to be someone who puts the purpose of the institution (educating students) over ego, so maybe such a person will never exist…

See here:

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/26/business/in-college-endowment-returns-davids-beat-the-goliaths.html?_r=0

My guess is very few large funds (>$1 billion) will ever adopt a simpler approach. There are a couple pensions I know that do this but no endowments I’m aware of.

What about the volatility of these returns? Endowments are generally seeking significantly lower risk profiles with more predictable cash flows. The 60/40 portfolio’s volatility may be too much for vehicles that have a more consistent withdrawal schedules like endowments.

Volatility is just one risk and most focus too much on volatility and miss the other risks they are taking to get that lower vol. 40% in high quality bonds have basically no vol whatsoever. Why focus so much on vol when you have a new-endless time horizon. More here:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2016/01/short-term-decisions-with-long-term-capital/

Well, they have a quasi-endless time horizon. On one hand, they have a very long investment horizon and theoretically should be able to stomach huge drawdowns in favor of higher returns. On the other hand, they generally have very strict withdrawal schedules that do not vary as much as the markets.

I think it’s a misconception that hedge funds are inherently riskier than equities or a 60/40 portfolio. Hedge funds are as risky as you tell them to be, since you’re the institutional investor. And from what I’ve seen, most PEFs ask for lower risk and lower return (except in Private Equity), since that more closely fits their investment mandate. Family offices and private individuals usually have the higher risk tolerance, since there’s not as much career risk there. That’s also why I think you’ve seen more pensions than endowments or foundations shun the hedge fund industry; their job is generally more political and paying no fees is the politically “in” thing to do right now.

I agree that volatility isn’t the best measurement for “risk”, but it’s probably one of the easiest ones to measure. Thanks for the response.

yeah it’s just really hard to make an apple-to-apples comparison but I agree that these funds basically are a perpetuity

Endowments seemingly have a different “generational” time horizon than individual’s that follow a 60/40 split…what would the returns have been on an 80/20 or 90/10?

True and most of those bigger funds only have 10-15% in bonds. Here are the numbers:

90/10: 5 yr +14.0%, 10 yr: 7.6%

80/20: 5 yr +12.9%, 10 yr 7.4%

This is like comparing Derek Jeter’s batting average to the league-wide batting average. Of course it’ll be better! You’re talking about the *average* of 800 funds of which there are bound to be many really bad losers bringing it down.

If you look at the top 13 Ivy + Alt Ivy endowment average returns, based on 2014 data, they outperform the Bogle portfolio on 5-year (13%) and 10-year returns (9.78%).

Sure, but those places also have something like 10% in fixed income. Have to change the comparison in that case. And my point was that it’s very difficult to emulate those top fund’s success

Very interesting. It truly is amazing (except perhaps to Bogleheads) that these very smart people with all their resources end up basically the same as the simplest of index portfolios. It would be great to see 20 year numbers – 10 years is kinda short for a definative answer.

True. Some longer-term returns in here:

https://institutional.vanguard.com/VGApp/iip/site/institutional/researchcommentary/article/InvResEndowPerf

From Jan 2000 through Jan 2016, your reference portfolio (40% VBMFX, 40% VTSMX and 20% VGTSX) had an annualized return of 4.65%, standard deviation of 9.54%, Sharpe ratio of 0.34, and maximum drawdown of 34%. At the end of Feb 2009, the *cumulative* total return of this portfolio was all of 0.93%! How do these numbers (incl. the volatility and Sharpe ratio that you gloss over) compare to the concrete figures for endowment funds that also invested in other asset classes over the same period? (BTW, at 3.53%, the standard deviation of VBMFX over the same interval was far from “basically no vol whatsoever,” as you stated below.)

longer-term numbers in here https://institutional.vanguard.com/VGApp/iip/site/institutional/researchcommentary/article/InvResEndowPerf

of course you could pick many times where this or any portfolio performed terrible. so it goes…

longer-term numbers in here https://institutional.vanguard.com/VGApp/iip/site/institutional/researchcommentary/article/InvResEndowPerf

of course you could pick many times where this or any portfolio performed terrible. so it goes…

The reason why I picked that 16+ year time frame was because I wanted to see the longer-term performance over a period whose start well predated the financial crisis. This is where alternative investments preferred by many endowments, incl. the small ones, would come into play. Again, without adjusting for risk, even with the simplest metric of the Sharpe ratio, comparisons of pure returns are not very meaningful. The Vanguard paper only states a higher SR of the balanced portfolio over 25 years against small and medium endowments (not large ones), but it does not say by how much.

From Jan 2000 through Jan 2016, your reference portfolio (40% VBMFX, 40% VTSMX and 20% VGTSX) had an annualized return of 4.65%, standard deviation of 9.54%, Sharpe ratio of 0.34, and maximum drawdown of 34%. At the end of Feb 2009, the *cumulative* total return of this portfolio was all of 0.93%! How do these numbers (incl. the volatility and Sharpe ratio that you gloss over) compare to the concrete figures for endowment funds that also invested in other asset classes over the same period? (BTW, at 3.53%, the standard deviation of VBMFX over the same interval was far from “basically no vol whatsoever,” as you stated below.)

> Here’s how the Bogle portfolio stacks up against the endowment funds over the *past 5 and 10 years*…

You need to use precisely the same time frame of analysis: for 10 years, from July 2005 through Jun 2015, and not (presumably) from CY2006 through CY2015. Over the former period, the Bogle portfolio of 40% VBMFX, 40% VTSMX and 20% VGTSX, had an annualized total return of 6.59% (when rebalanced quarterly) and 6.48% (when rebalanced monthly). So, it did NOT return more than an average endowment fund over $500M. Similarly, over the 5-year period through Jun 2015, the Bogle portfolio returned 10.05% (with quarterly rebalancing) and 9.96% (with monthly rebalancing), not outperforming an average endowment fund over $1B or under $25M.