The latest SPIVA mutual fund scorecard was released last week and it was more of the same from the past few reports — the majority of active mutual funds underperformed their respective benchmarks over the past 1, 3, 5 and 10 year periods.

These numbers are well-documented at this point so I’ll spare you the details. It can be difficult to keep up during a relentless bull market, so many active fund managers are hanging their hat on the fact that they can make up for this underperformance once the next bear market hits. This makes sense in theory and is one of the more appealing sales pitches for active management. Let’s see if this claim has any validity.

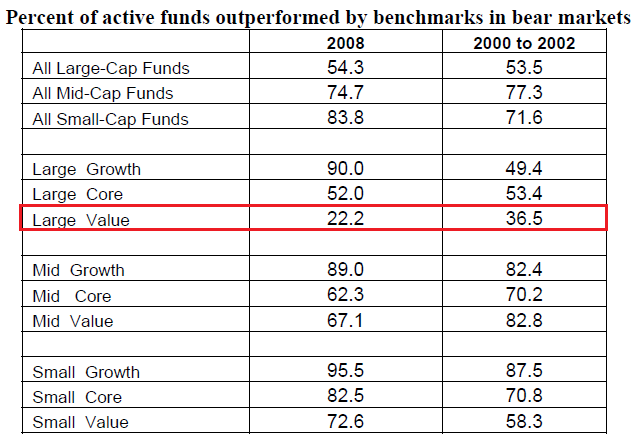

The following table comes from the 2008 SPIVA scorecard following the bloodbath that saw broad-based U.S. stock indexes fall anywhere from 31% to 44% in 2008 alone:

You can see that the majority of active mutual funds underperformed in the two previous bear markets. There was, however, a lone exception in both downturns — larger cap value funds. In 2008, nearly 80% of large cap value funds outperformed their benchmark while almost 65% outperformed in the 2000-2002 bear market.

This makes sense when you consider that most true value investors require a margin of safety when making a purchase. They don’t chase and overpay for expensive growth stocks. This type of a disciplined approach can pay off when other investors loosen up their risk management during a bull market. This is one of the reasons that value stocks are lagging behind growth stocks right now.

But investors can’t expect to outperform during every phase of the market cycle. As an extreme example, according to the 2009 SPIVA report, the top-performing U.S. equity mutual fund in 2008 ended up performing dead last in 2009 once the recovery took hold. This fund literally went from first to worst.

Obviously, actively-managed mutual funds don’t constitute the entirety of active portfolio management strategies and decisions. There are other ways of managing risk, including tactical asset allocation. Tactical asset allocation involves changing your asset class weights over time to account for the current environment, while a static asset allocation approach relies on sticking with a set target to each asset class with a rebalancing process to stay within the stated targets.

If you’re going to go down the tactical path you just have to ask yourself a few questions in advance:

- Is my personality well-suited for a tactical asset allocation approach or is a static allocation better for my needs?

- Do I have the requisite skills and knowledge to be able to accurately judge a tactical process?

- Do I have the patience and discipline to actually follow and implement a tactical process?

- Does the process in question rely a systematic rule-based strategy or is it based on the intuition of a professional investor?

There are no easy answers to these questions, but I would be skeptical of any advisor or portfolio manager that makes promises that they can get you out of the market before trouble hits and back in at the bottom with perfect timing. It’s possible to manage risk with your asset class exposures, but you can’t expect to fully sidestep all losses and fully participate in all gains.

Think about all of the people that called the financial crisis. Many pundits and investors who anticipated the real estate bust were heralded as geniuses by the media and investors alike. How many of those people have been completely wrong about the ensuing rally and economic recovery? Has anyone proven themselves completely reliable on both sides of the cycle?

All of which is to say that it’s never going to be easy. You can’t expect to have it all. Every investment style or strategy has its flaws. The trick is to find the one that you understand that gives you the best chance of minimizing your own flaws.

Source:

SPIVA 2008

Further Reading:

How to Preserve Capital During a Bear Market

Not All Active Funds Consistently Underperform

Why Value Investing Works

Why do you personally think this anomaly only presents itself for large-cap value funds, as opposed to mid-cap or small-cap funds? That seems contrary to what you’d expect.

Good question. Not sure on the exact reason, but my guess would be that the large cap value benchmark is actually easier to beat than the small & mid value based on the construction of the indexes. Being more broad-based in small & mid can actually be a positive while value can be added by being selective in large caps.

Pure speculation on my part, but that’s my best guess. The returns in the small & mid indexes have been pretty great since inception.

[…] I saw this Barron’s article (pay-walled) and decided to see what all the fuss is about in the active manager comeback story. It seems every few months there are press articles or analyst research pieces that proclaim the beginning of “the stock picker’s market”. There was one in Financial Times in January 2014 or one here in August 2013. In the blogosphere, Josh Brown and Ben Carlson have chronicled this game nicely here, here, here and here. […]