“Early adopters reap the initial high returns and low correlations of a novel asset class; then one or more multiple academic and trade journal articles will describe those benefits, always accompanied by plump, curvaceous two-dimensional mean-variance plots. Last come Readers Digest versions in the mass media.” – William Bernstein

The common refrain from many financial advisors is that you should allocate 5-10% of your portfolio to commodities. They will tell you that if you look at the long-term studies that date back to the 1970s it shows that commodities offer diversification benefits and equity-like returns with similar volatility characteristics.

Unfortunately, it would have been nearly impossible to invest in those uncorrelated returns. Here’s William Bernstein on commodities:

Before 1990, almost no actual U.S. portfolio managers could, let alone did, invest in commodities futures, because doing so involved, at least metaphorically and oft times actually, getting into all of the relevant pits, dressing in funny jackets, and jostling a scrum of sweaty, panicked ex-linebackers braying for money – or at least hiring a broker who did.

Fast forward a quarter century; now the biggest players are the likes of Pimco and Oppenheimer, who have sold the gullible on the pre-1990 record of commodities futures – never mind that prior to 1990 this strategy had been, for all practical purposes, non-investible.

So it’s difficult to prove if these long-term diversification claims are legitimate.

How about our more recent experience in commodities?

Commodities never really hit the big time in portfolio allocations until the mid-to-late 2000s. And of course, the reason this happened is because of Wall Street’s tendency to market the most recent asset class du jour that has shown the best performance.

Following the tech bust, the S&P 500 basically went nowhere for a decade. Yet from 2002-2007 alone, a basket of commodities was up nearly 150%. That meant nearly every financial firm rushed out to show that they were an expert in the commodities arena by rolling out as many fund offerings as they could.

Once everyone rushes out to buy the new-new thing, it’s difficult to find buyers as things reverse course. That’s exactly what has happened in the last few years as commodities are still underwater since the fallout from 2008.

I decided to see if Bernstein’s claims were correct. And it just so happens that the Dow Jone UBS Commodities Index returns date back to 1991 so it fits perfectly with his assertion that things may have changed once commodities became investable as an asset class.

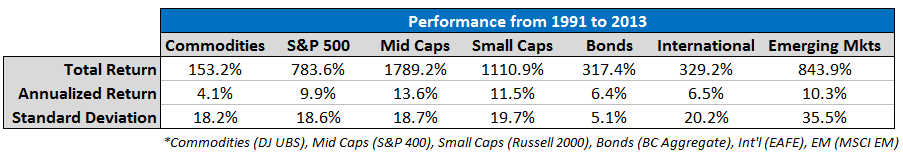

Here are the results from 1991 along with a handful of different markets for comparison purposes (click to enlarge):

It looks like one of the claims on commodities is correct — they do have stock-like volatility which is nearly identical to the standard deviation of the S&P 500. But even with the huge returns in the mid-2000s, the performance was fairly abysmal considering total bond market returns were one-and-a-half times better with less than a third of the volatility.

A recent research paper goes a step further and shows that commodities actually increase overall portfolio volatility with a decrease in risk-adjusted returns:

At the same time, however, we have also found that this comes at the cost of an increase in volatility. Therefore, the growing appetite for commodities is likely to produce more volatile portfolios.

This paper has shown that the correlation between commodity and equity returns has substantially increased after the onset of the recent financial crisis.

At the same time, an investment strategy which also includes commodities in a portfolio produces substantially higher volatility and not always produces higher Sharpe ratios. This is at odds with the common notion that commodities serve as a hedge.

You would have been much better off with exposure in the resource-rich emerging market stocks as opposed to the actual physical commodities.

Cullen Roche has discussed this in the past on his blog, Pragmatic Capitalism:

I prefer to think of commodities as something that are an input or a means to helping us innovate. If you’re bullish on oil price dynamics you shouldn’t go buy barrels of oil and store them in a locker somewhere. You should find the companies who leverage the use of that commodity and will benefit by innovating through the use of that input. Don’t bet against innovation. Bet on it.

The problem I have with commodities as a long-term asset class is the fact that they don’t generate any earnings or pay dividends like stocks. They don’t make periodic interest income payments like bonds. Really, they don’t build long-term value in a business sense. They are a function of cost and need.

Plus, if you hold a diversified portfolio of stocks, you should already have commodities exposure through energy, mining, agriculture and natural resource companies. Basic materials make up roughly 3% of the S&P index while energy stocks make up around 10%. Most international markets contain heavier commodity stock weightings.

I have no idea what will happen to commodities in the future. If we have severe inflation with some sort of price shock, they could earn a solid return. And I’m sure there will be short-term periods where they do better than stocks and bonds.

But I don’t think that the evidence shows that you absolutely have to hold commodities in a portfolio. A diversified global portfolio of stocks and bonds should do the trick.

Sources:

Commodities – They have (almost) no place in your portfolio (Prag Cap)

On the correlation between commodity and equity returns: implications for portfolio allocation (BIS)

Skating where the puck was: the correlation game in a flat world

Seems like commodities carries the volatility of stocks with a fraction of the return. There doesn’t seem to be any reason to have them in a portfolio, other than for speculation.

Correct, they are a speculative asset. That’s not to say they can’t do well in certain environments, but over the long haul I don’t see any need for commodities exposure.

This article totally misses the point. Who cares what the historical returns of commodities are? What is totally missing is the correlation of commodity returns with stocks and bonds. In other words, regardless of independent return and volatility characteristics, does the addition of commodities to a diversified portfolio improve the overall risk and reward? The answer is a resounding yes. Go back to investments 101 and come back with an article that incorporates MPT.

I’m pretty sure you missed the point of MPT. The goal is to get the highest return for each level of risk. Commodities increase risk (as defined by MPT) but not return. Hence they create an inefficient portfolio on the curve.

You’re not just looking for low correlation. If that were the case then cash would be an ideal asset. From 1991-2013 t-bills returned 3%/yr with a correlation of 0.15 with the S&P 500. Commodities returns 4.1%/yr with a correlation of 0.14.

Also going back a decade, commodities returns show a correlation of 0.91 with emerging mkts even though EM stocks returned a total of 200% and commodities returned 9% (total). Take your volatility with higher returning sectors not just lower correlation.

[…] of economic revival, and basic resources, hit by concerns of a China slowdown.” Meanwhile, do you need commodities in your portfolio? Performance analysis of commodities as a broad asset class since 1991 shows “performance was […]

[…] Do You Need Commodities in Your Portfolio? (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

[…] Do you need to hold commodities in your portfolio? (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

Great article, I have wondered about this as my stocks have boomed and the value of my allocation to commodities (via USCI) has actually declined in value over the last few years. This articlet would have been even better if you had included some charts showing commodity, bond, and stock correlations since 1991, and also some MPT portfolio curves with and without various amounts of commodities, as well as other pertinent data. It would be excellent if you would write a more detailed follow-up article.

That’s a good idea and one that I have been considering following some other comments from this article. Not only the correlations from that time but also how the correlations change over time. Thanks for the comment and check back in as I’ll post some follow up analysis and thoughts in the next couple of weeks.

What would be the argument against commodities if, for instance, gold and silver paid dividends?

Through the ETNs of SLVO and G LDI one can now earn dividends on holding gold and silver.

It still costs money to extract commodities from the ground. There are also storage and transportation costs involved. So the only way you are able to get those dividends is when the market price is greater than those costs. This can happen, but I consider commodities more of a trading vehicle than a long-term asset class for these reasons.

[…] received a number of comments on my Do You Need Commodities in Your Portfolio? post from fans of investing in commodities. Many asked why commodities wouldn’t be the perfect […]

[…] Do you need commodities in your portfolio? […]

[…] Wealth of Common Sense asks the question Do You Need Commodities in Your Portfolio? A fair question as we seek to build properly diversified investment […]