A lot has been made about the potential for a bond bubble with interest rates near historic lows and not much room to fall any further. Even though rates are down this year, investors have been worried for some time about what happens when rates do eventually rise.

As a quick refresher, bond prices and interest rates are inversely related. So as rates rise, prices fall and vice versa. This makes sense since no one’s going to want to pay full price for a bond that yields 3% if market rates are now at 4%.

The conditions in any two investing environments are never the same, but we do have historical evidence on what has happened in the past when interest rates rose from similar levels as those seen today.

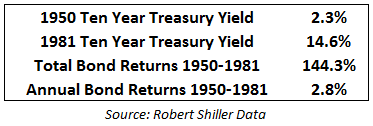

Interest rates on ten year treasuries rose by over 500% from the beginning of 1950 to the end of 1981. Here you can see that rate increase along with the performance of these bonds over that period:

You didn’t make a whole lot of money in bonds during this time, but you didn’t get completely slaughtered either. The worst annual return for bonds from 1950 to 1981 was -5%. That’s a terrible day in the stock market.

What many fail to realize when they call it a bond bubble is that even the worst bear market in bonds is completely different than even a run-of-the-mill correction in stocks. Bond bear markets are more like a death by a thousand cuts rather than a straight dive down. That’s because fixed income and equity securities aren’t structured in the same way and have completely different risk profiles.

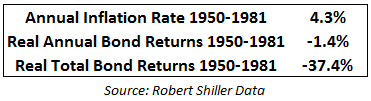

Investors should really be worried about inflation risk as opposed to interest rate risk in bonds. Look at what happens to the bond performance over that same period once you take into account the inflation rate:

Bonds weren’t really crushed by the rise in interest rates. Higher rates effected performance, but nominal returns were still positive because eventually investors were able to make up for the price losses through the increases in yield.

The real returns paint a completely different picture as your purchasing power was slowly eroded over time in bonds in an inflationary environment.

There could be more pain in other sectors of the bond market based on credit quality and maturity, but the point is that bonds were never meant to be long-term return enhancers for your portfolio.

This isn’t anything new. Over multi-decade time horizons bonds have never really been the most consistent way to beat the rate of inflation. They pay you a fixed amount of income, so as inflation rises you are getting paid less and less from a purchasing power perspective. Your mortgage works the opposite way in your favor as those long-term debt payments slowly decrease from inflationary pressure.

So does this mean you should dump all of your bonds for fear of a rise in rates or inflation?

Not if you’ve determined that they fit within your risk profile and asset allocation plans. If you just sat on bonds from now through the next few decades will you be happy with your performance? Probably not. But if you use them as a source of stability and for rebalancing purposes then yes, bonds still have a place in a well-diversified portfolio.

Bonds were not a great long-term investment in this 30+ year environment of rising rates and inflation. That’s obvious. But bonds did their part when stocks went down. When stocks fell 11% in 1957, bonds were up nearly 7%. In 1966 when stocks fell almost 10%, bonds were up 3%. And when stocks fell 37% from the start of 1973 through the end of 1974, bonds were up nearly 6% in total.

In a diversified portfolio you use your bonds to buy stocks (or for spending purposes if taking distributions from your portfolio) when the stock market falls so you aren’t forced to sell your stocks at a low point in the cycle and lock in losses.

In that way bonds act as your dry powder during stock market sell-offs in the same way that you should harvest stock gains into bond funds when stocks are in a bull market.

It’s not going to be possible to have the same type of 5-6% annual returns in high-grade bonds that investors have become accustomed to for the past 30+ years. The returns will be much lower going forward from here. But bonds can still play a role in your portfolio with the correct perspective, plan and expectations.

Further Reading:

Resetting Bond Return Expectations

[…] What does the bursting of a bond bubble look like? (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

[…] Wealth of Common Sense: – What does the bursting of a bond “bubble” look like? – A lot has been made about the potential for a bond bubble with interest rates near historic […]

[…] What does the bursting of a bond “bubble” look like? by A Wealth of Common Sense […]

[…] bonds don’t see huge crashes like stocks do because of the way they’re structured (see: What Does the Bursting of a Bond “Bubble” Look Like). The largest annual loss in long bonds is ony around 15% in nominal terms. Inflation is the real […]

[…] shows why inflation is a bigger risk than an increase in interest rates to long maturity bond holders. The average and median real returns for yields under 3% over ten and […]

[…] See also: What does the bursting of a bond “bubble” look like? […]

[…] accounts, I followed this up with another mistake. I started reading news stories about the bond bubble. As Warren Buffet […]

[…] Reading: What Does the Bursting of a Bond Bubble Look Like? Market Returns During Ray Dalio’s 1937 Scenario What’s the Worst 10 Year Returns from a […]

If everything is overvalued, then cash is undervalued. A crash in the bond market would put the US into default because its ability to borrow and roll over its debt would be gone.

Yes as some point cash will be an undervalued asset as it gives you a call option if/when stocks fall. It just depends on how patient you can be in the meantime.

Also, the US can’t ever technically default because they control the printing press. We can always print more money. It’s just inflation that we’d have to worry about.

Printing money has its limits. Once inflation goes above about 10% to 30% per year, trading partners would no longer accept contracts based on our currency (we would have lost our reserve currency status). In the long run, we need to produce as much as we consume. If we do not, who will give us foreign aid or buy our bonds? The Fed could buy the bonds, but that would push inflation higher. Argentina and Venezuela each print their own currencies, but they have reached the point where the only way they can meet their socialist spending requirements, is to start producing as much as they are consuming. China is willing to provide a lifeline in exchange for access to resources, but China has severely cut its acquisition program recently.

I am by no means an expert on this subject. Here’s a take by Cullen Roche if you’re interested:

http://www.pragcap.com/can-a-sovereign-currency-issuer-default

Thanks for the link to that article. I have to agree with everything the author says. Insolvency for a business is defined as being unable to make payments as they come due. The US has been bypassing this problem by printing money. The Fed makes a computer entry to increase their bank balance. Then they use their higher bank balance to buy US bonds which transfers the newly created money to the US Government. Printing money is actually a form of taxation since the government gets all the new money before the economy experiences the inflationary effect.

Here is an article I wrote about the impossibility of growing our way out of our current $18 trillion debt.

I am very glad I am 73 and that my wife and I have no children. In 2000 the US Debt to GDP ratio was 55%. Now it is 101%. We were able to grow our way out of our debt problem after WWII because of the huge increase in labor participation (16 million soldiers came home and women entered the workforce), a world that needed our factories and the Marshall plan which financed our exports. We will not be able to grow our way out of our debt this time. I have been playing with spreadsheets forecasting our Debt to GDP ratio years into the future. There is no scenario where our Debt to GDP ratio does not go to infinity. For instance, we could grow our way out of our debt

problem if we grow our GDP by 7% per year for the next 10 years while keeping the average interest rate on our debt below 3% and limiting inflation to 2%. Unfortunately, there is not a hope in heII for the existence of such a scenario.

Don’t kid yourself that our Deficit is only $483 billion. Our real Deficit is the increase in our Debt for the year which was $1086 billion. That is because we do a lot of spending that does not go through the Budget (our government is lying to us, believe it or not). Our Debt increased in every year in which Clinton showed a Budget Surplus. For National Debt figures by fiscal year, see https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/histdebt/histdebt_histo5.htm

For the ratio of Debt to GDP for each fiscal year, see

http://useconomy.about.com/od/usdebtanddeficit/a/National-Debt-by-Year.htm

There are solutions, but politics will prevent them. We could raise the age for Social Security benefits and Medicare to 70 or 72. The original

Social Security program was dependent on half the population dying without receiving benefits, We need to eliminate welfare, food stamps, child tax credits, low income tax credits and Medicaid. I spent 2 years living in Colombia, and the Colombian population manages to survive without all these entitlements. When Colombians don’t have money, they “diet”. The USA will reach that point via insolvency and the subsequent austerity. That will happen as soon as there is an alternative world reserve currency. China has loaned more money to other countries in the past 2 years than the IMF since it was founded in the 1930s.

Now here is the bad part. The rate at which automation is occurring has reached the point where jobs are being eliminated faster than they are being created. I don’t expect to pay $90,000 a year to live in a nursing home. I expect to be assisted by an attended-care robot. In a few years, I expect to use a self-drive Uber car (goodbye 160,000 Uber drivers). Also, goodbye to over 2 million truck drivers. Try to think of jobs that won’t be eliminated by automation. There are not many. Design, maintenance and repair of robots will very soon be done by robots. The next generation has no future.

Check out the book Average is Over by Tyler Cowen (if you haven’t already). He covers this topic well. His case is that there will be a widening gap between those who are able to work with technology and those who won’t It’s going to be an interesting and bumpy shift for sure.

[…] Yet historically bond market “bubbles” are not the same thing as a stock market bubble. […]