It’s been almost four years since the S&P 500 has had a 10% correction. That makes it the second longest such streak since World War II, trailing only the period from 1990 to 1997 that went longer without experiencing a double digit loss.

Bonds, however, the investor’s go-to asset class for safety, have experienced two separate corrections of 10% or more in that time when looking at long-term U.S. Treasury bonds. In fact, long bonds are in the midst of a correction as we speak because interest rates have finally risen over the past couple of months.

Using Ibbotson data on long-term U.S. treasuries going back 1926*, I looked back at the historical corrections to see how often they experienced double-digit losses. From 1926-1957 there were actually none, but they did come close a few times:

- -9% in 1931

- -8% in 1939

- -8% in 1951-1953

- -9% in 1954-1957

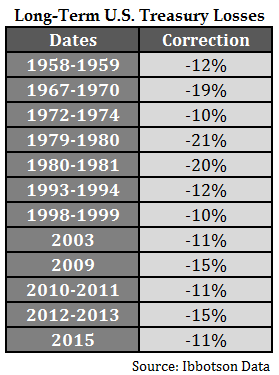

It wasn’t until 1958 that a double digit correction finally took place in long-term treasuries. Here are each of the drawdowns since then:

Roughly one out of every five years there has been a double digit correction in the long bond with an average loss of almost 14%. Another was to look at it this is that over 40% of all double-digit bond market losses have come since 2003 alone. Why is this the case? It could be that investors are losing patience and trading more often, increasing short-term volatility in a long-term asset. Or it could be that bond market volatility picks when interest rates are lower, especially in long maturity bonds. It’s probably a little of both.

But why were there no large corrections in the 1926-1957 time frame?

I reached out a reader who’s my resident market historian to ask for his take on the pre-World War II lack of large losses in treasuries. Here’s what he had to say:

My understanding is that until the mid-1950s, Treasuries were much less volatile than they have been since then. From 1942-1951 long bonds were pegged by the Fed at around 2.25% yield. But before then, during 1926-1941, Treasuries just didn’t react very much to bubbles and crashes in stocks. Apparently under the gold standard, bond investors regarded long-term prices as stable, and took little heed of short-term economic and price trends.

Even though these are long-term assets, it seems that there are now more momentum investors and macro traders than ever trying to play this space. The chase for yield has also caused many investors to increase the duration in their bond holdings to earn more income. The current state of interest rates doesn’t necessarily mean bonds are in a bubble as many presume, but it does mean losses are more likely to occur than they have in the past.

If you’re invested in longer maturity bonds you have to understand the risks involved. All else equal, volatility in bond prices from interest rate moves is higher the longer you go out on the maturity and duration spectrum and the lower the level of interest rates.

For example, the duration of the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) is currently 17.1 while the duration for 7-10 Year ETF (IEF) is only 7.6. This means you could expect a 1% rise in interest rates to lead to something approaching a 17.1% decline in TLT prices, but just a 7.6% fall in the IEF price (this doesn’t include the income earned on these funds).

None of these historical drawdowns come close to matching the worst historical bear markets in stocks, but they’re probably larger than most bond investors would care to sit through.

It’s worth remembering that a higher yield can lead to higher risk.

Further Reading:

Are We Witnessing a Melt-Up in Long-Term Bonds?

What Returns Can Investors Expect in Long-Term Treasuries?

*The data used in these correction numbers are monthly returns. That means some of the corrections could have been more severe using daily data in-between the month ends.

An intriguing question, for those who maintain a static bond allocation, is how far out to go in duration.

In publicly-disclosed unleveraged versions of Ray Dalio’s All Weather Portfolio (such as the one described by Tony Robbins and reviewed here on Nov 18, 2014), a 40% weighting in long Treasuries (i.e. 20-year maturity) is used. Since even long Treasuries are still less volatile than equities, they require both long duration and a heavy weighting to serve as an effective counterbalance to stocks.

On the other hand, 7 to 10 year Treasuries historically have offered about the same return as 20 to 30 year Treasuries, with lower volatility. On a standalone basis, Treasury investors hugging the right-hand edge of the yield curve don’t get paid for the extra volatility they endure.

Ultimately it’s a question of context and correlations. If Treasuries continue to be mildly anti-correlated to stocks, then longer-term Treasuries can improve the Sharpe ratio of a stock-bond mix. But if we should return to the bad old days of 1979-1980, which produced the worst drawdown ever in Treasuries at the same time stocks went south, shorter maturities will be the best place to hide.

What to do, what to do?

What to do indeed. It sure seems like plenty of investors went short duration a few years too early. You wonder how impatient they’ve become. I think there will probably be more value-added from those giving portfolio allocation advice on the bond side than the stock side over the next decade or so. Always interesting.

And thanks for the contribution to this one.

Efficient market theorists say that beating the bond market consistently is as unlikely as beating the stock market. But the bond king Bill Gross, and crown prince Jeffrey Gundlach, are all about active management (though the largest bond fund, at Vanguard, is an index fund).

It isn’t that hard to beat the BarAgg by taking on more risk. But that strategy periodically will experience ‘hundred year floods’ like 2013.

Thanks to central banking, short-term interest rates are anything but random. This affects the yield curve as well, in ways that potentially can be exploited, even by unlettered dabblers lacking a PhD Econ.

Agreed. Intermediate term bond benchmarks are actually one of the easiest ones for active managers to beat:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/not-active-funds-consistently-underperform/

Composition of the index means tilting away from treasuries or mortgage bonds helps (although that changes the risks too).

[…] A history of bond market corrections. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

[…] Records – WSJ Violent bond moves signal tectonic shifts in global markets – Telegraph A History of Bond Market Corrections – Wealth of Common Sense Chinese stocks suffer biggest weekly loss in 5 years – […]

Love this blog. It is also worth noting that austerity has constricted both the supply and liquidity of bonds, making them scarce in a time of high demand. Scarcity doesn’t matter much when you own them as it drives prices up, but when sellers appear all at once, it matters quite a bit. Funny how an obsession with misguided debt to gdp politics as a driver of instability has created an instability of its own. The laws on unintended consequences.

Good point. When the central banks take the bonds out of circulation the supply and demand dynamics naturally kick in (which is what they want, until things turn south, as you point out). I still think there will be a flight to safety in sovereign bonds when stocks have a bear market but other areas such as high yield and corporate debt could run into some problems.

[…] A history of US bond market corrections – A Wealth of Common Sense […]

What to do? Well, beyond 10 years you get more volatility than return, so I’d go with a 1-10 year bond ladder (or the bond fund equivalent). This balances interest rate risk and reinvestment risk. Trying to guess interest rates movements is a mugs game, as those who moved to short term bonds in recent years have discovered. I also like to keep corporate bonds in a separate fund to treasuries, as corporates tend to depress the price rise of aggregate bond funds during times of financial stress.

Agreed that laddering is a great way to spread out your interest rate risk. One of the first things I learned in this business is that it’s a waste of time to try to predict the direction/magnitude of interest rt moves. Not an easy game to play.

[…] A History of Bond Market Corrections by A Wealth of Common Sense […]

do you have above stats for intermediate bonds?

Good question. I only have the BC Agg going back to the 1970s. I’ll take a look and see what it looks like.

The worst one I could find in the BC Agg (which would be an approximation of the entire bond market & intermediate term) was -13% in the 1979-80 period. The data only goes back to 1976 so much of the period was in a falling rate environment but that’s the only double digit correction I could find.

[…] A historical past of US bond market corrections – A Wealth of Common Sense […]

[…] couple weeks I looked at the history of corrections in long-term U.S. treasury bonds. I received a few follow-up questions from people asking for the same information on intermediate […]

[…] Fonte: A History of bond market correction […]

[…] than lament the low yields, why not look for undervalued bonds during a market correction? More bond market corrections have taken place since the market lost 15% in 2009, despite the new level of volatility, bonds are […]