A reader asks:

As a retail investor, how does one go about assessing the investment performance of a security or even an index fund beyond looking at the historic performance which Ben Carlson recently described as chasing performance? Linked to this, can you please explain a backtest in simple terms, and what is a good way to do a backtest for an average investor?

Backtests are a double-edged sword for investors.

On the one hand, having an understanding of financial market history, from booms to busts and everything in-between is one of the most important variables for long-term investment success.

On the other hand, if you torture the data long enough you can get it to say just about anything you want. It’s easy to data-mine past performance until it offers extraordinary results that could be more or less useless under real-world market conditions.

It is true that performance chasing can lead to suboptimal results if you’re not careful.

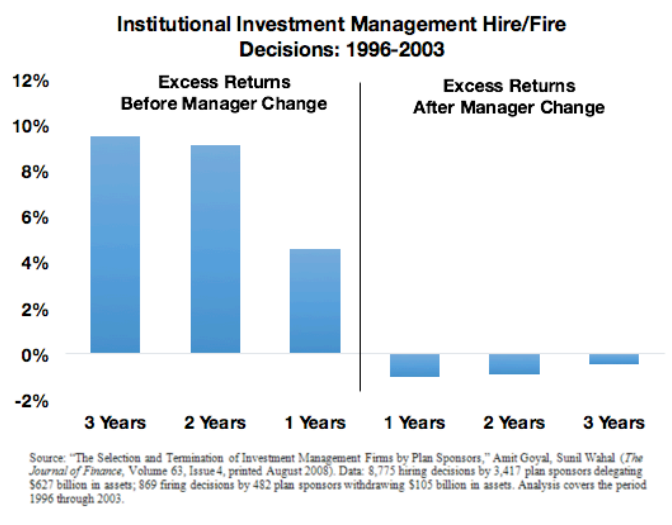

And it’s not just individual investors who fall prey to the siren song of short-term outperformance. Institutional investors who manage tens of millions or even billions of dollars do the same thing.

Here’s a chart I used in Organizational Alpha to show how institutional investors tend to invest in money managers that have outperformed in the recent past, only to see them underperform once they’re hired:

Chasing alpha is not a strategy.

The biggest problem I have with most backtests is that it’s always going to be easier to find a strategy that worked well in the past than to discover one that works well in the future.

Most backtests fail to consider costs, frictions, liquidity and the fact that investors of the past weren’t armed with the same level of information and technology we have available at our fingertips today.

Backtests can help provide context but you have to think through how realistic it would have been to pull them off under the circumstances at the time.

It’s also impossible to backtest emotions.

The 1987 crash looks like a blip on a long-term stock market chart but it felt like the second coming of the great depression at the time. With the benefit of hindsight, every crash in history looks like a wonderful buying opportunity. No one knows when they will end in real-time.

There are plenty of strategies that worked in the past that simply don’t work anymore because they get arbitraged away or they simply stop working.

Up until the 1950s, stocks used to have higher yields from dividends than bonds had from income payments because corporations had to convince investors to invest in the riskier asset class.

The rule of thumb was that every time stocks yielded less than bonds it was time to sell and when they yielded more than bonds it was time to buy. And this worked beautifully…until it didn’t.

The yields flipped in the late-1950s and stayed that way for decades, breaking what was once a foolproof backtest.

So what are some helpful backtests?

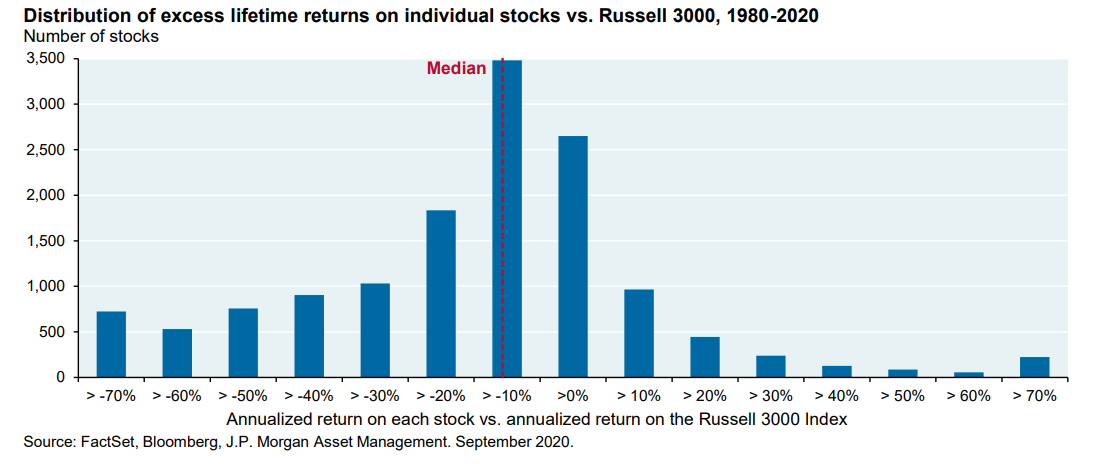

This chart from JP Morgan is a personal favorite:

It shows how a small number of winners in the stock market more than make up for an even larger number of losers. Surprisingly, most individual stocks underperform the market itself.

Henrik Bessembiner’s research shows similar results in that most individual stocks underperform cash (T-bills) over the long haul.

My biggest takeaway from these backtests is the need for diversification in your holdings so you ensure the winners are part of your portfolio. It’s much easier to pick the losers than the winners.

Studying the past can’t help you predict the future but it can provide context in terms of the relationship between risk and reward. An understanding of the risk and return profiles for stocks, bonds and cash can help you determine the right asset allocation for your specific needs and goals.

Knowledge of the relationship between risk and reward can also keep you out of trouble when hucksters and charlatans make unrealistic promises of returns that are too good to be true.

Risk is a lot easier to predict than returns so a general understanding of volatility, drawdown profiles and the probability of loss is important before investing in anything.

Knowing what you own and why you own it is the first line of defense in terms of risk management.

Anyone can create a backtest that shows phenomenal past performance. It’s the front-test that gets you when reality differs from the spreadsheet.

A good way to perform a backtest for an average investor is to gauge the potential for loss and what the impact would be on both your finances and your emotions.

Backtests are unemotional. Humans are not.

We talked about this question on the latest edition of Portfolio Rescue:

Blair duQuesnay joined me again this week to discuss questions about big purchases, leveraged ETFs, 401k loans and real estate investments.

Further Reading:

10 Things You Can’t Learn From a Backtest

Podcast version here: