A reader asks:

Can we get a breakdown from Ben on the pros and cons of long-term vs. short-term bonds?

I’ve probably gotten more questions/comments about bonds over the past 6 months than I’ve received in the previous 6 years.

The huge losses in fixed income last year have forced investors to become more thoughtful about how they allocate to this asset class.

Let’s briefly look at the pros and cons of the different bond durations and then get into the historical returns over various interest rate cycles.

For long-term bonds, the pros include:

- You get more bang for your buck when interest rates fall since higher duration means more sensitivity to rate movements (and prices have an inverse relationship with rates).

- Long bonds tend to be one of the best hedges against recessions of the deflationary variety.

- You can lock in higher yields for longer. In the early-1980s but you could lock in 15% yields on long-term bonds for 30 years!

- Long bonds should earn higher returns since they involve more interest rate and duration risk.

The cons for long bonds include:

- They can get crushed when interest rates rise and/or inflation rises. Look no further back than last year to see this in practice.

- There is far more volatility in relation to interest rate changes since the duration is so much higher. Long bonds can experience huge price swings in both directions when rates go up or down.

- You can get locked into lower yields for a lot longer which can hurt you if interest rates rise quickly.

Short-term bonds are kind of the opposite. The benefits include:

- There is little-to-no interest rate risk (depending on the duration) which helps during periods of rising interest rates.

- There is much less volatility than long bonds when it comes to price changes in relation to yield changes.

- There is less reinvestment risk if rates rise because short-term bonds mature faster than long-term bonds.

The downsides of owning short-term bonds are as follows:

- You can’t lock in higher rates for very long. Yes, yields are 5% right now on short-term bonds but those rates could come down in a hurry if we go into a recession.

- Expected returns are lower because you’re not taking as much duration or interest rate risk.

- Short-term bonds don’t provide as much recession/deflation protection since you don’t get the price appreciation component that long bonds do when rates fall.

A lot of investors fell in love with the idea of long-term bonds over the past 20-30 years because they generally provided much higher returns and cushioned the blow during most stock market sell-offs…until last year that is.

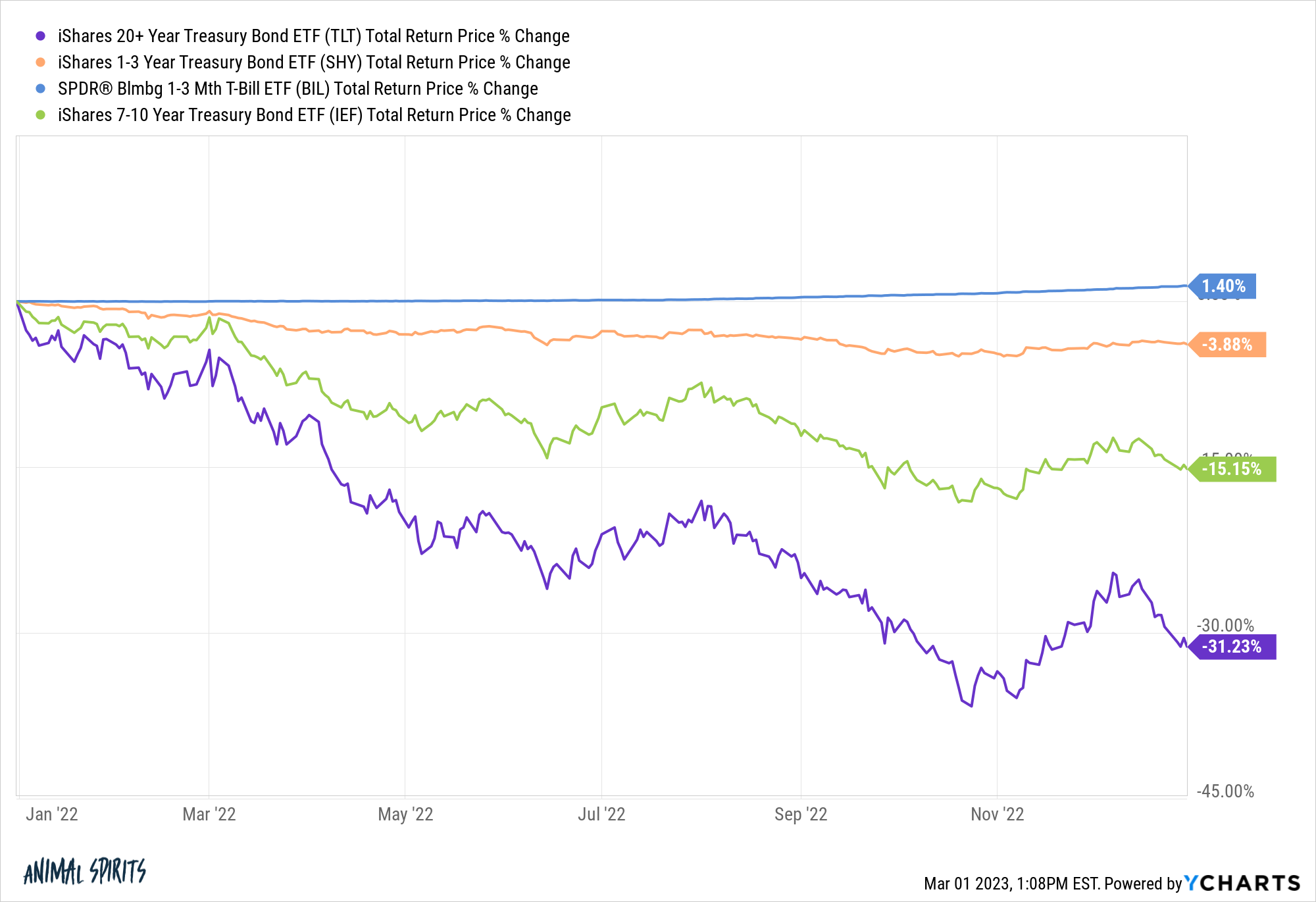

These were the performance numbers for long bonds, intermediate-term bonds, short-term bonds and ultra-short-term bonds (basically cash) in 2022:

Long bonds got crushed, falling way more than the stock market. Intermeditate-term bonds also got beat up pretty badly while short-term bonds fell a little and T-bills were unaffected.

That was a bad year but it was just one year. It can also be instructive to look at the secular interest rate cycles to see how different bond maturities have fared historically.

Let’s look at the historical performance to see how these bonds have done over the past 100 years or so to get a sense of how they do in different interest rate regimes

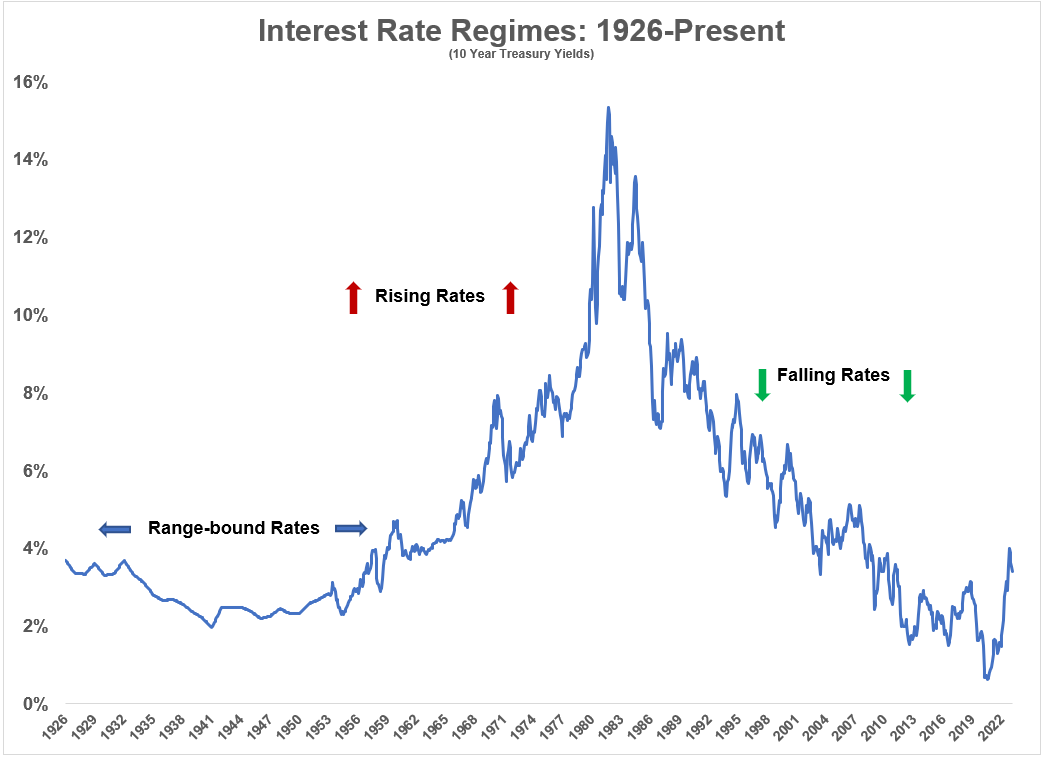

The way I see it there have really only been three secular interest rate regimes since the 1920s:

Phase 1 was from the 1920s through the 1950s when rates were rangebound. Rates on 10 year treasuries were more or less stuck between 2% and 4% for 30 years or so.

Phase 2 was from the early-1950s through the early-1980s when rates went up, up and away. We saw 10 year yields go from 2% to 15% over a 3 decade period.

Finally, Phase 3 is the one most investors of today got used to, which was falling rates from the early-1980s highs in the mid-teens all the way down to the next-to-nothing yields we saw during the Covid panic.

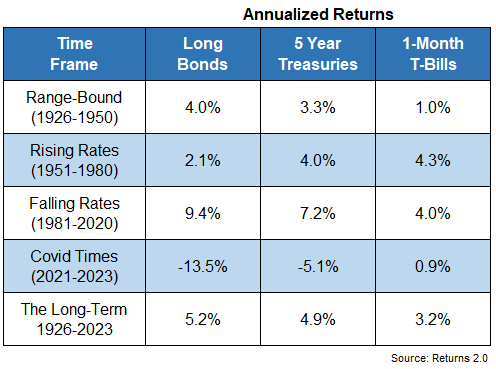

Here are the performance numbers for long, intermediate and short-term bonds in each of these regimes along with the long-run returns:

When rates didn’t go anywhere things lined up as you would expect. Riskier bonds outperformed risk-free T-bills.

However, in an environment of higher rates and higher inflation, cash outperformed both intermediate-term and long-term bonds. One-month T-bills crushed long bonds for 3 decades.

Those higher rates, in turn, benefitted long bonds in a big way over the next four decades during one of the greatest bull markets we will ever see in fixed income. It’s certainly not normal to earn 7-10% annual returns in bonds.

Now we’ve entered a new regime.

I don’t know if the aggressive rate increases over the past 18 months or so will continue. Rates might go back to 2%. Maybe they’ll go even higher if inflation and economic growth remain strong.

It’s hard to say at this point. I know that sounds like a cop-out but predicting the direction and path of interest rates is really hard.

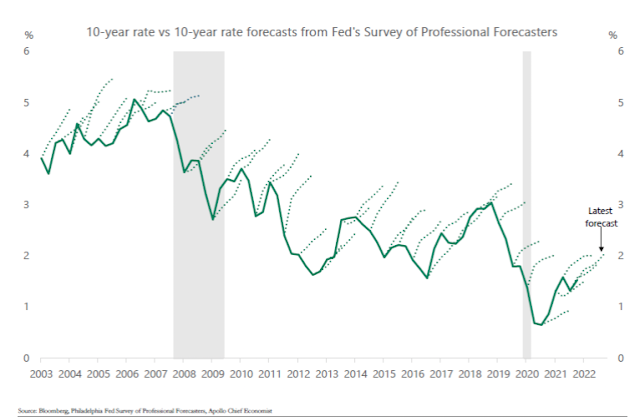

This chart from Torsten Slok at Apollo shows interest rates going back to the early-2000s along with the forecast of rates from the Fed’s Survey of Professional Forecasters:

They basically never get it right.

I don’t like making investment decisions based on predictions or macro forecasts. Making predictions about the future is hard enough but even if you nail the macro forecast, the financial markets might not react how you assume depending on what’s already priced in.

I prefer to think about bonds from the perspective of risk and reward. I like to accept volatility in my portfolio where I’m being paid for living through the ups and downs — like the stock market.

I’m not a fan of taking on a lot of duration risk even in “normal” times (if there is such a thing) when the yield curve isn’t wildly inverted.

Sure, if long bond yields go to 5%, 6%, 7%, I’d be happy to talk. But when long bond yields are 3-4% and T-bill yields are 5% I don’t see the need to introduce volatility into your portfolio.

If we do go into a recession and rates fall, duration will pay off in a big way and short-term bonds will lag. I just like the idea of earning 5% and basically completely taking volatility off the table for the fixed income side of your portfolio right now.

You just have to figure out how much volatility you can handle and what kinds of risks you are trying to protect yourself from when investing in bonds.

It really comes down to how you view risk and reward and your appetite for volatility.

We discussed this question on the latest edition of Portfolio Rescue:

Bill Sweet joined me on the show again today to talk real estate tax advantages, tax planning for retirement, selling single stock positions with large embedded gains and backdoor Roth IRAs.

Podcast version here: