I don’t believe there is one singular way to invest your money. If there was everyone would invest that way.

Every strategy and philosophy has its pros and cons.

The good strategy you can stick with is far superior to the great strategy you can’t stick with so a lot of this comes down to who you are as an investor.

There are a number of factors that determine the type of investor you are.

Experience shapes your views of the risk-reward nature of the financial markets. Your formative years as an investor and the various market environments you’ve lived through can have an outsized impact on how you invest your capital.

Personality is a big one. I strongly believe your temperament and emotional disposition play a strong role in the type of strategies you’re drawn to as an investor.

Mentors early on in your investment lifecycle can also determine the path you choose to take as an investor.

My first boss in this business instilled in me the importance of asset allocation, portfolio construction and risk management when implementing investment plans.

When I started that first job out of college my knowledge of the financial markets was as close to nil as you could possibly get. I had a steep learning curve because I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life.1

So my other mentors when I finally decided to apply myself to the learning process were the authors of the books I was reading to play catch-up.

I learned about investing at the school of John Bogle, Charley Ellis, Nick Murray, Warren Buffett and Jeremy Siegel.

The biggest lesson these legends taught me was the importance of time horizon when investing your money.

The ability to think and act for the long-term is one of the few advantages left in the markets.

This is why I was such a big fan of Siegel’s Stocks For the Long Run. That book helped shape my understanding of the need to think in terms of decades when it comes to stock market investing.

WisdomTree’s Jeremy Schwartz has been helping Siegel for a number of years when it comes to the research for his books. Schwartz recently shared some data for the upcoming release of the 6th edition of this classic.

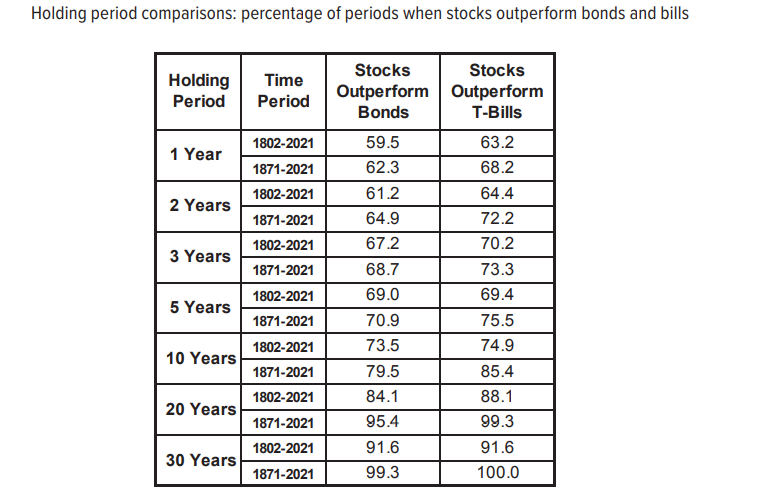

This one is a favorite of mine:

There are no guarantees when it comes to investing in the stock market. As much as some people would like to think so, the stock market does not work like a casino. You don’t know the exact odds before placing a bet (or trade).

But we do know that history tells us the longer you invest in the stock market, the greater your odds of success when it comes to beating safer assets.

I don’t have data going back to 1802 but even if we look back at the period from 1928 to 2021, cash has beaten the stock market in 30 out of the last 94 years. So one-third of the time on an annual basis you would have felt better about yourself as an investor by simply sticking your money in a money market fund or short-term T-bills than investing in the stock market.

However, the long-term average return on the stock market would turn $10k into more than $67k over 20 years. That same $10k in cash turns into just $18k.

Does this mean you should blindly put all of your money into the stock market?

Of course not!

But thinking through the historical return profiles of stocks, bonds and cash can help you determine how to plan for time horizons ranging from short-term to intermediate-term to long-term and allocate your portfolio accordingly.

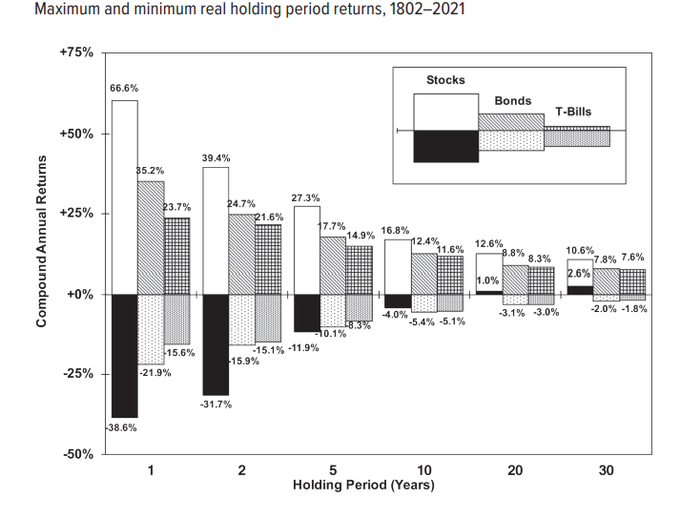

Here’s another way of looking at this from Schwartz and Siegel:

This one shows the range of outcomes depending on your holding period.2

The shorter your time frame the wider your range of returns in everything, especially the stock market. The longer you go out the less volatility there is in the average and range of results.

My general rule of thumb is I don’t invest money in the stock market that I will need in the next 4-5 years or less.

It’s just not worth the risk.

On the other hand, holding cash for 2-3 decades at a time brings its own set of risks in terms of losing purchasing power.

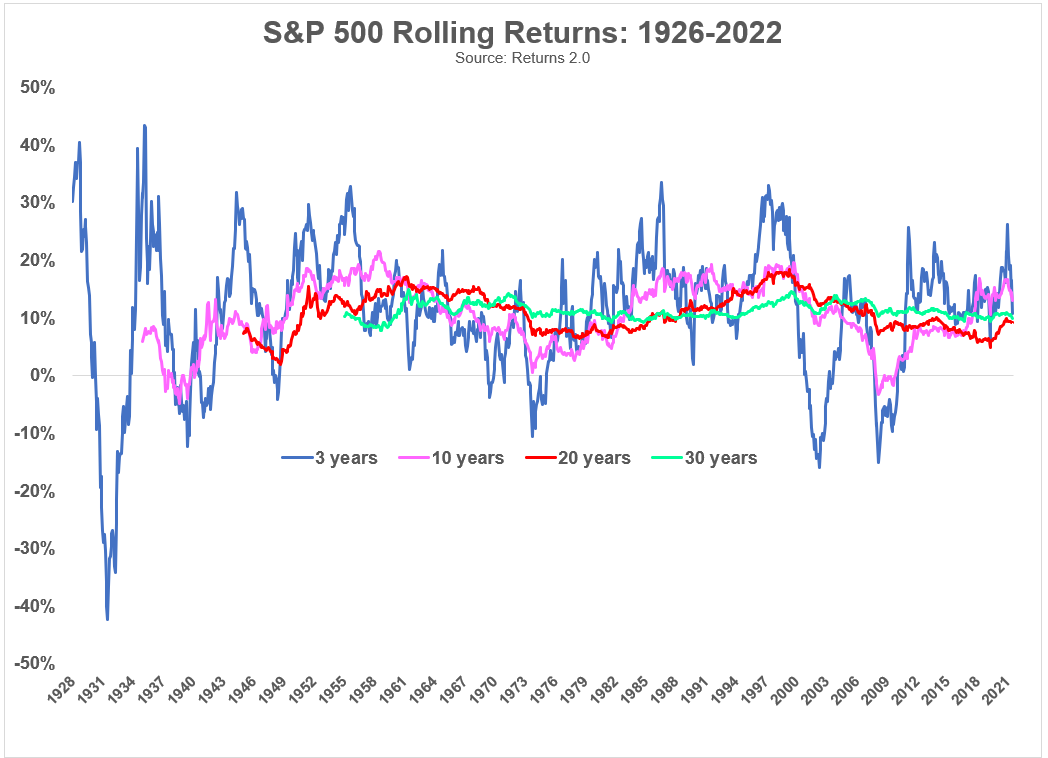

Here’s another way to visualize the volatility in stock market returns over time:

I’ve seen studies that suggest the average holding period for a mutual fund for individual investors is around 3 years. After that people get bored or want to chase performance or simply find something new to invest in.

Three years might seem like an eternity when you’re living through it (just think about everything that’s transpired over the past 3 years) but it’s relatively short in terms of stock market investing. Just look at the wild swings in rolling 3 year returns over time.

Things begin to smooth out a bit once you get to 10 years, remain only in positive territory over 20 years and really narrow once you get to 30 years.

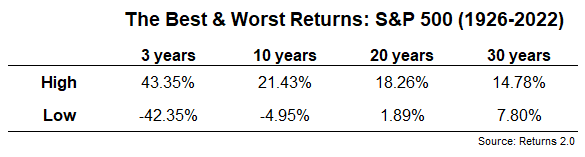

Now look at the highs and the lows for each group:

You can still get your face ripped off over a 3 year window of time in the stock market. At 10 years you can still lose a little money.

The U.S. stock market has never been down over 20 or 30 year time frames. Could it happen? Sure, anything can happen. I can’t predict the future.

But should that be your baseline when viewed in a probabilistic framework?

Do you really want to bet against human ingenuity, corporate profits and the human desire for progress?

I know I wouldn’t want to make that bet.

There are lots of ways to succeed as an investor.

Over the long run, the stock market remains the best place to do so, assuming you have the patience to make it there.

Michael and I discussed stocks for the long run and more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

What Returns Should You Expect For Stocks & Bonds Over the Long Haul

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Take a bow if you have a simple portfolio this year (Humble Dollar)

- On bullshit in investing (Noahpinion)

- The risk of deflation is now greater than the risk of prolonged inflation (PragCap)

- Good luck (Young Money)

- The second derivative of vibes (Kyla’s Newsletter)

1Looking back on it now it’s hard to believe how little time and effort I put into thinking about what I actually wanted to do for a job after college.

2Quick reminder – these are real returns (after-inflation) so that’s how cash can be negative at times.