Former New York Fed chair Bill Dudley put a scare into the markets this week when he said the Fed needs to bring down asset prices to help fight inflation. This was his reasoning in a Bloomberg piece:

In contrast to many other countries, the U.S. economy doesn’t respond directly to the level of short-term interest rates. Most home borrowers aren’t affected, because they have long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. And, again in contrast to many other countries, many U.S. households do hold a significant amount of their wealth in equities. As a result, they’re sensitive to financial conditions: Equity prices influence how wealthy they feel, and how willing they are to spend rather than save.

Here’s the kicker:

Investors should pay closer attention to what Powell has said: Financial conditions need to tighten. If this doesn’t happen on its own (which seems unlikely), the Fed will have to shock markets to achieve the desired response. This would mean hiking the federal funds rate considerably higher than currently anticipated. One way or another, to get inflation under control, the Fed will need to push bond yields higher and stock prices lower.

I understand the thinking here. People are wealthier than ever coming out of the pandemic, especially those in the top 20% or so.

This group more or less complains about higher prices but then keeps right on paying them because they can. The problem is it’s probably going to be the bottom 50% that don’t own financial assets that gets hurt the most if we do go into a recession.

But the idea is if you can put a dent in the wealth effect and make borrowing more expensive it should slow demand.

I do worry the law of unintended consequences here though.

Take the housing market.

Housing supply is at all-time lows while prices have been skyrocketing.

Now that the Fed has signaled they will raise interest rates we’ve seen a swift repricing of mortgage rates, going from less than 3% to around 5% in a hurry.

In theory, higher rates should bring prices down because housing just got way more expensive for new buyers.

But higher interest rates will likely cause homebuilders to cut back on new home construction.

And with interest rates so low just a few short months ago, supply could become even more constrained since it will be difficult to get people to trade up from a 3% to 5% mortgage for a more expensive house.

It could become a stand-off between more expensive housing and low supply.

This could make things ever worse for people in the market for a house.

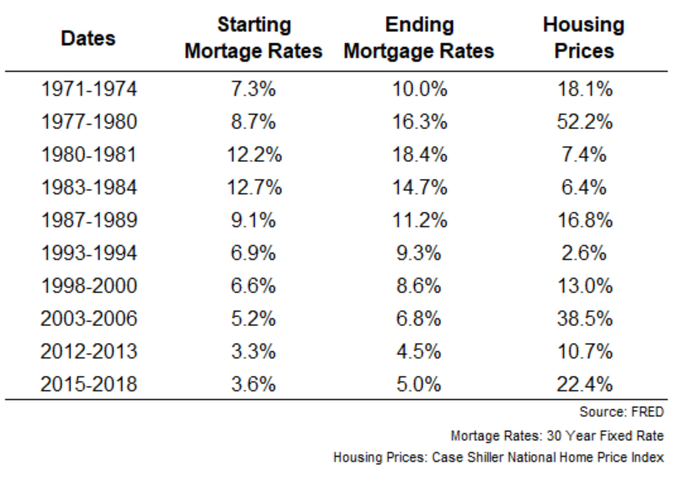

Plus housing has held up well historically when mortgage rates rise, especially during periods of high inflation:

It’s certainly possible this relationship won’t hold this time when you consider the appreciation in housing prices since the pandemic and the speed of the move higher in mortgage rates.

But that’s the potential problem for the Fed — the market is moving way faster than they are. A move this fast in rates could become a problem.

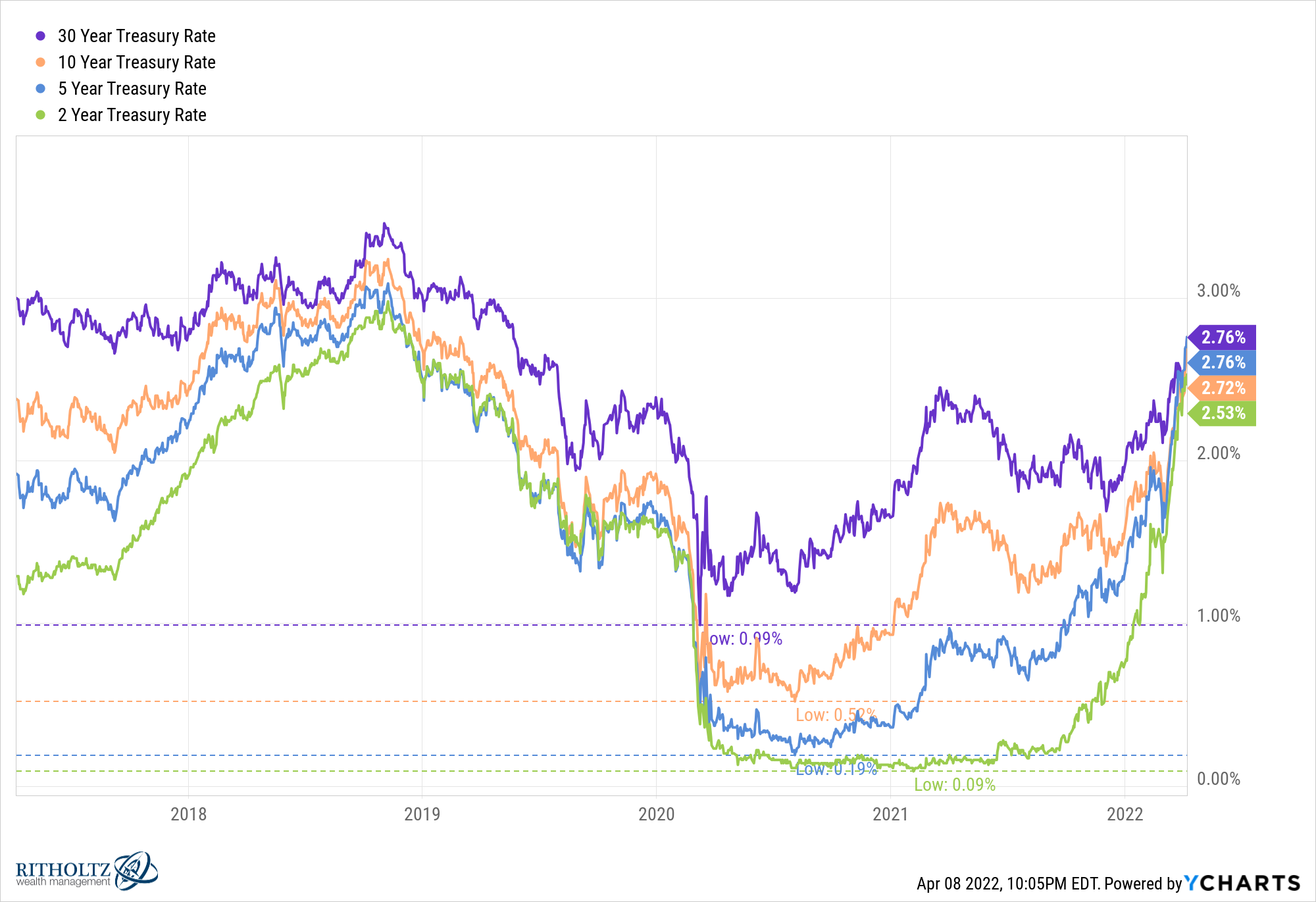

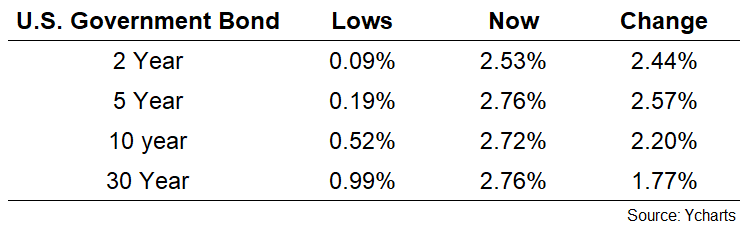

While the Fed has raised its benchmark rate just 0.25%, government bond yields have already moved way higher:

Those are some pretty big moves off the lows:

To be fair, the response to the pandemic shoved yields off a cliff to their lowest levels of all-time. And when compared to inflation levels these yields are still relatively low.

I guess I’m struggling with the idea that the Fed is going to raise rates, throw us into a recession and simply lower rates again during the downturn.

It feels like the Fed is simply raising rates now to lower them in the future. It’s like dumping a plate of food on the floor with the intention of cleaning it up.

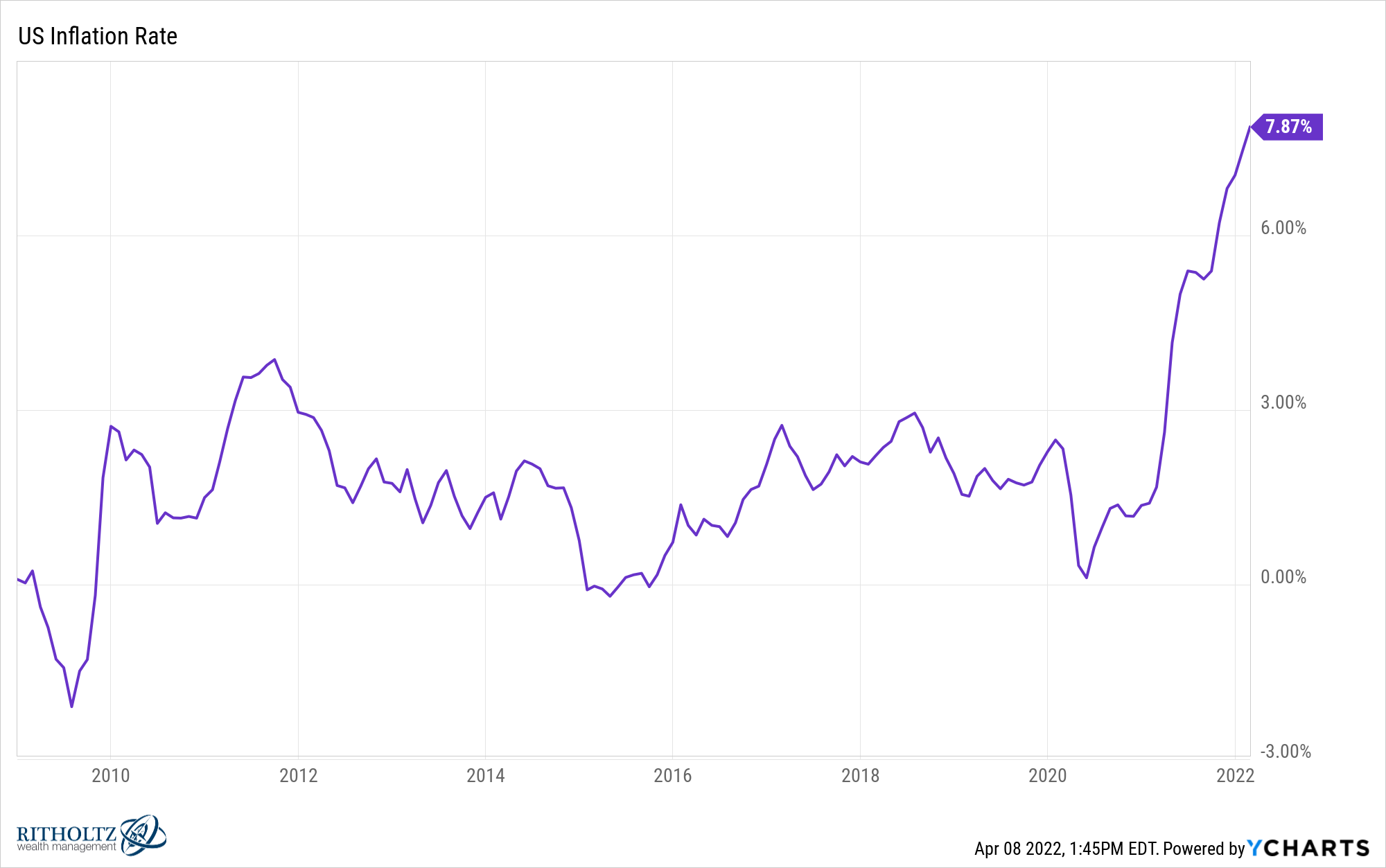

I think the people are overreacting because no one really has experience dealing with an inflationary environment.

From 2008-2020, the U.S. inflation rate spent just 8 out of 144 months with inflation above 3%. There wasn’t a single month where inflation was above 4%.

And do you remember the biggest economic complaints in that period?

Wages are stagnant.

The robots are going to take all of our jobs.

You should count yourself lucky if you have a job in this economy, let alone ask for a raise.

Now look at the labor market:

Walmart Inc. is raising starting pay for in-house truck drivers to as much as $110,000 a year and expanding a program that trains its existing workers to become drivers.

The company, in a bid to keep its supply chain running smoothly, is setting starting salaries for its truck drivers between $95,000 and $110,000 a year, up from an average starting salary of $87,000, said a Walmart spokeswoman.

Are we sure we want to slow this down? We’ve had 12 months of a hot labor market and the Fed wants to snuff it out already?

Obviously, there are trade-offs in these things. Wages are now growing but so are prices. Inflation presents its own set of problems.

I’m just asking the question: Which one is worse — higher than average inflation (and growth) or lower than average inflation (and growth)?

I’m not suggesting the Fed should keep its foot on the gas pedal. But isn’t there some middle ground between easy monetary policy and a recession?

My controversial take here is I am anti-recession. People lose their jobs, businesses fail, wealth falls and there are often unintended consequences.

Obviously, recessions are a natural extension of our financial system but I would rather avoid creating one on our own if we can help it.

It feels like the Fed is going to push us into a recession.

That’s a mistake.

Further Reading:

Are We Heading For a Recession?