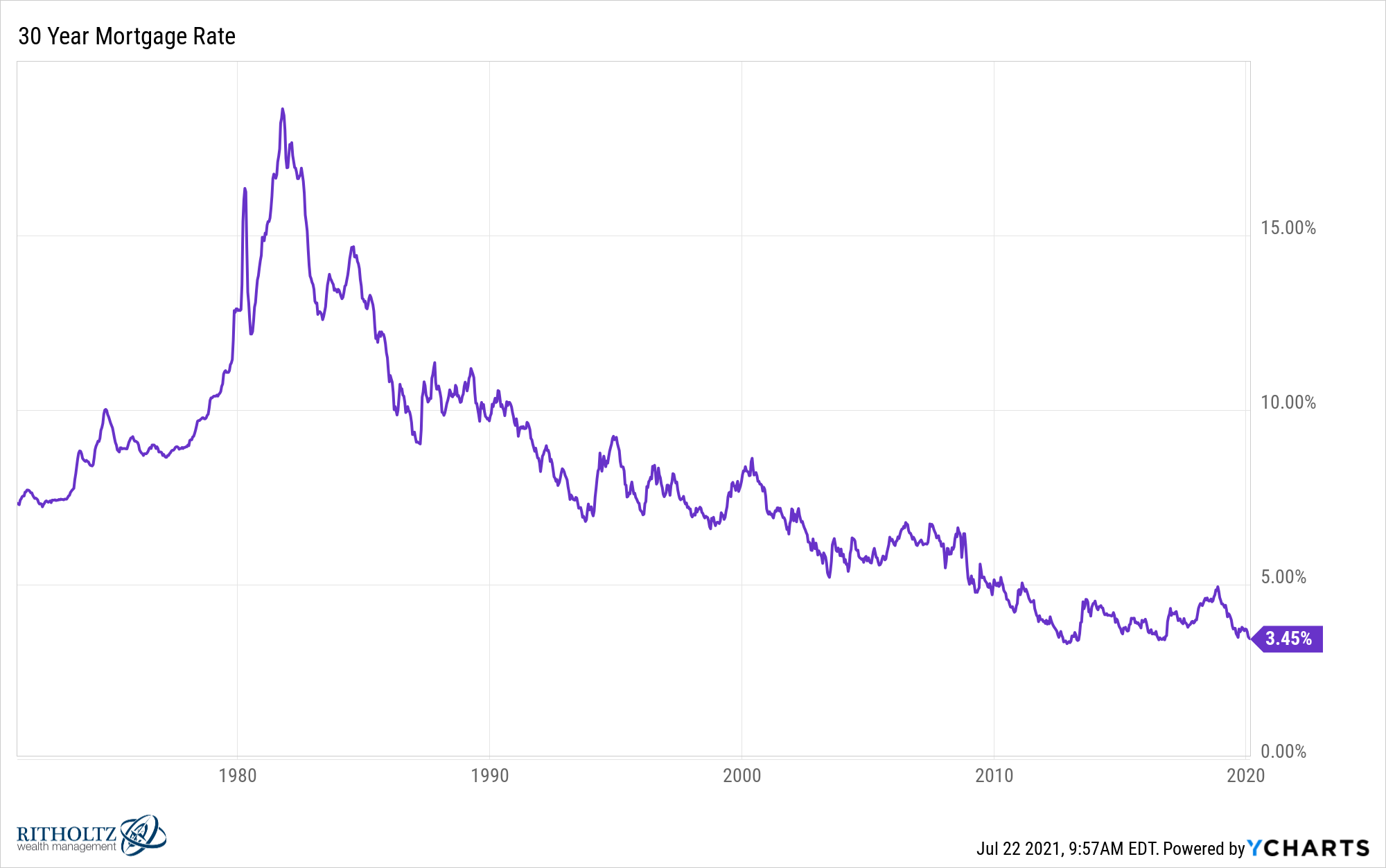

Coming into the onset of the pandemic in early-2020, mortgage rates were under 3.5% after flirting with 5% in late-2018:

And although rates fluctuated in the 2010s, the 30 year fixed rate mortgage averaged just over 4% for the decade and spent around half that time under 4%.

This 4% level is worth noting because going back to 1971, the average 30 year mortgage rate had never breached that number until the 2010s.

Lower mortgage rates are notable because they make things much easier on homeowners when it comes to monthly payments.

A $350k mortgage at 5% rates would be a monthly payment of around $1,880 over 30 years (not including taxes, insurance and such).

That same mortgage at 3.5% would equate to a monthly payment of $1,570. That’s a savings of $310/month and more than $3,700/year.

That’s real money.

In theory, a lower discount rate should then drive up home prices. If you can afford a $2,000 monthly payment, at 5% interest rates that’s a $375k mortgage. At 3% rates, that’s a $500k mortgage.

Lower rates should naturally drive prices higher as homebuyers begin increasing their price ceilings. And a lower discount rate should increase the price of financial assets.

Before the pandemic, prices were rising as rates were falling. The Case-Shiller National Home Price Index was up 27.4% from 2015 through February of 2020. This was a time when mortgage rates were below 4% more than 60% of the time.

Yet since March 2020, U.S. home prices have surged 15.6%.

Low rates certainly helped this surge but you can’t say they’re the sole cause.

Here’s another way to look at this — in the 15 months prior to March 2020, mortgage rates averaged 3.9% and housing prices gained 4.3%. In the 15 months since, mortgage rates averaged 3% and gained 15.6%.

Interest rates helped start the fire but emotions provided the accelerant that took things to another level.

The Wall Street Journal recently profiled a couple whose house selling experience encapsulates this idea perfectly:

Until recently, Brooklyn residents Michelle and Dan Mannix thought they would never sell their country home in Orient village on Long Island’s North Fork.

“We used it the whole pandemic and it was a godsend,” Ms. Mannix said of the house, which the couple, who are serial entrepreneurs, purchased 14 years ago for weekends and vacations. When the pandemic broke out, they moved to Orient full time with their son. “I would say, ‘We’re never going to sell.’ Then all of a sudden, things started to shift.”

They watched in awe as home prices on the North Fork shot up. A house a few blocks from theirs sold in 72 hours for $2.5 million, “much more money than anybody had seen recently,” said Ms. Mannix, 50. “That was like, ‘Well, wow. What could you get for ours?’ That got our wheels spinning.”

It takes more than interest rates to get those wheels spinning.

This is why emotions will always matter more than interest rates or other fundamentals when it comes to the markets.

It’s not like rates hit some magical level that causes people to decide to buy a house all at once.

Watching your neighbors get rich is an experience you can’t quantify with a number.

Seeing someone in your neighborhood sell their house for more than you think it’s worth elicits feelings that don’t show up in economic data points.

Anecdotes can shape our view of investing and the markets far more than cold hard data ever could.

Rates were already at generational lows before the pandemic hit. Now they’re even lower. Low mortgage rates are unquestionably having an impact on people’s ability to buy a home. Rates matter but they can always be trumped by human nature.

If rates rise from here it would make sense that housing should cool off.

But that relationship is not set in stone. Housing prices don’t have to crash if mortgage rates rise. If demand from homebuyers is still there and their finances are in good shape it doesn’t really matter if rates rise from here.

Mortgage rates were 6-7% during the housing bubble of the early-2000s.

The dot-com bubble inflated when the 10 year treasury yielded 6-8%.

Interest rates are an important component in every market imaginable. They act as a benchmark, a hurdle rate, a cost of capital, an income component in portfolios and more.

But interest rates alone aren’t enough to make markets go crazy.

For markets to go crazy you need human emotions to kick into overdrive.

It’s bizarre to think it took a pandemic for this to happen in the housing market but here we are.

Further Reading:

What If Interest Rates Don’t Matter as Much as We Think?