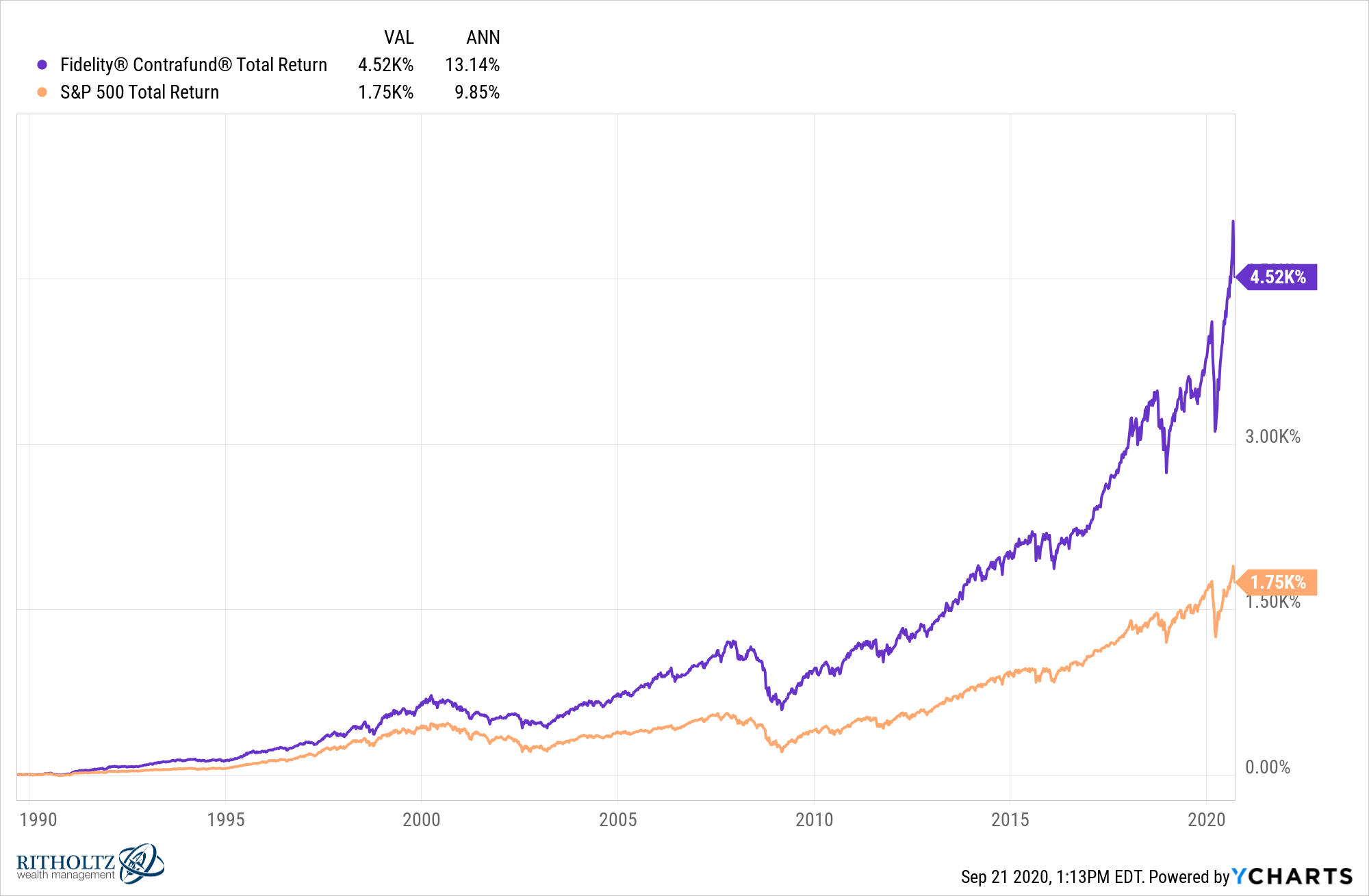

Will Danoff of the Fidelity Contrafund has one of the best long-term track records in the entire fund business, handily trouncing the S&P 500 over the past 30 years:

Barry Ritholtz interviewed Danoff on Masters In Business recently and it was interesting to hear the portfolio manager’s thoughts on how benchmarking plays a role in his decision-making process. Barry asked Danoff why he wasn’t benchmarked to more of a growth-focused index such as the Nasdaq 100:

DANOFF: Yes. There’s a lot of truth to that. I am much more of a growth investor. I am, in my opinion, a capital appreciation fund with a growth bias. So, I do have a go anywhere — a large grow-anywhere component and it’s just the technology. It’s been such a powerful tidal wave that I’ve probably stayed in technology longer and bigger than I would have expected.

Benchmarks are important and Fidelity, for legal reasons, does not want to change the benchmark. It’s actually sort of time-consuming and cumbersome to change benchmark. It probably made…

RITHOLTZ: And the S&P 500 is hard enough to beat as is.

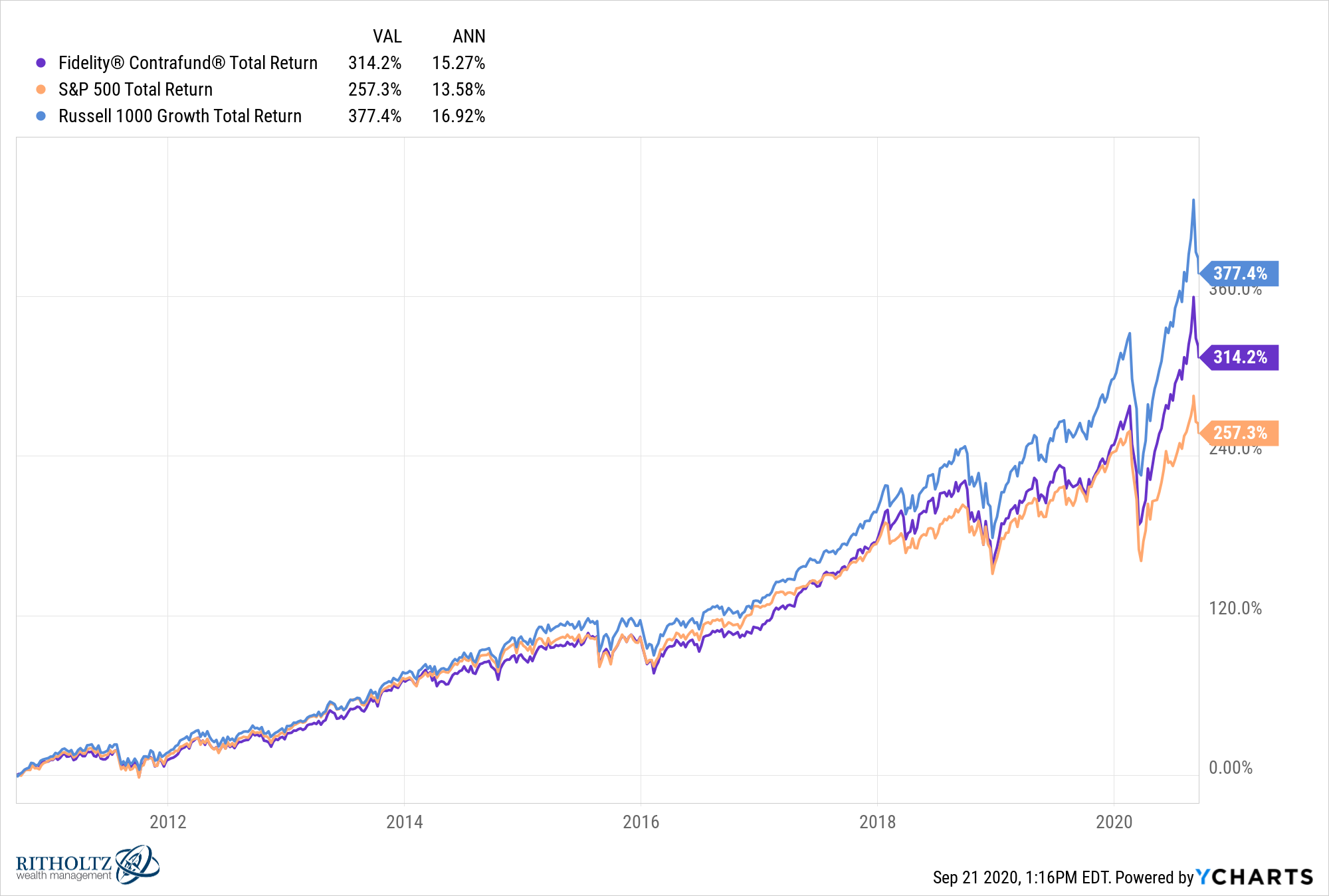

DANOFF: Yes. I mean, there are some of my larger more institutional investors who do look at the Russell 1000 growth. Frankly, the performance has not been as good and I don’t know if my bench was the Russell 1000 growth if I would be even bigger in some of these [tech] names.

Danoff has crushed the Russell 1000 Growth Index since inception as well but he has trailed it over the past 10 years:

He has a go-anywhere mandate but admitted that having the S&P 500 as his benchmark may have held him back from investing more in the big tech names in the fund (Facebook, Netflix, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, etc.).

There are two different ways of looking at the pros and cons of benchmarking as an investor.

On the one hand, a proper benchmark offers investors the ability to track their actively managed funds against an alternative. In Danoff’s case, his investors could own an S&P 500 or Russell 1000 Growth mutual fund or ETF if they’re not happy with his performance. Benchmarks can also allow you to see where an active investor went wrong from a performance attribution perspective.

On the other hand, benchmarking can lead to career risk. One of the reasons the massive rise in index fund investing doesn’t have me worried is because so much of the money coming into that space is from higher priced active mutual funds that were closet index funds. Many of those funds closely tracked the benchmark so investors are just doing so now at a much lower price point in a more tax-efficient wrapper.

Danoff doesn’t fall into the career risk bucket here because he has a phenomenal track record but it was surprising to hear him admit the choice of benchmark could have impacted the position-sizing in his fund somehow.

How you choose to benchmark yourself in other areas of life can impact your decisions as well:

How other people invest. One of the things I’ve noticed about people who brag about their investment success is they’re often far more willing to share their successes than failures.

We’ve all had friends who claim to have sold out at the top just before a huge plunge in the stock market or bought bitcoin in 2011 or Google just after its IPO.

But you never hear these same people talk about the fact they didn’t have the nerve to buy back in after they sold or that they also bough bitcoin at the $20k peak in 2017 after giving a price target of $400k or the other stock picks they made that went on to lose money.

Benchmarking yourself strictly against other people’s winning investment ideas will make you feel like a failure at all times. No one bats one thousand in this game.

How other people live. The Wall Street Journal reported American families who make more than $98,000 in pre-tax income have an average of almost $92,000 in non-mortgage related debt, which includes things like credit cards, auto loans and student loans.

Averages like this don’t always tell the entire story but there are obviously plenty of people who have far more debt than they should.

When you see other people buying new cars, boats or other toys it can lead to a sense of entitlement.

I work hard. I should be able to buy nice stuff too.

There’s a huge difference between buying stuff and being wealthy. Unfortunately, when you see those around you buying stuff it’s hard to avoid the temptation because we benchmark ourselves against the stuff we see and wealth isn’t something you can see parked in someone’s driveway.

Someone else’s career. Chris Rock is arguably one of the funniest people on the planet. He is probably in my top 5 for best stand-ups of my lifetime. I’m excited to see what he can do in the new season of Fargo.

According to a new profile in The Hollywood Reporter, Rock has had a rough go of it in recent years:

At 55, he’s finally on the other side of a messy divorce from his wife of nearly two decades, and in “a ton of therapy” for the first time in his life. He had already worked through plenty on the road, too, exposing his infidelity, porn addiction and custody struggles to sold-out arenas, and later in one of two $20 million Netflix specials.

“I’m talking from hell,” he’d say at every stop, often crafting jokes about having to take shitty TV work to cover his alimony payments. And for a period, there was a flurry of announcements — movies, a book, even a Super Bowl ad — that suggested money was, in fact, a motive.

We’ve all spent some time day-dreaming what it would be like rich and famous but there is a downside to being one of the most recognizable people on the planet. It’s a cliche at this point to say that money doesn’t buy happiness because money sure can solve a lot of problems.

But it sure doesn’t buy contentment or make it any easier to stay out of your own head sometimes.

Benchmarking yourself against people who are more successful than you could provide the motivation to get better but it could also blind you to the fact that no one’s life is perfect.

Further Reading:

The Tyranny of Benchmarking