When I wrote this piece for Fortune a couple of weeks ago it seemed apt to compare the market volatility to the ups and downs of the European debt crisis of 2011.

At the outset of this downturn, we were seeing 3% and 4% moves in both directions. Then last week the market said to 2011, “Hold my Truly.”

The daily moves we’ve seen over the past 7 trading sessions are incredible. There hasn’t been a single day with a gain or loss with an absolute value of less than 4%. It’s been down 8%, up 5%, down 5%, down 10%, up 9%, down 12%, up 6%, down 5% and probably some crazy number today as well.

We know why stocks are acting so erratically — we’re in the midst of a global pandemic the likes of which we haven’t seen in more than 100 years.

But there are psychological reasons investors are so quick to panic sell and panic buy during volatile markets like this. Here I outline some of the reasons why this is the case and why you may have had trouble sleeping in recent weeks.

*******

In 2019, there wasn’t a single daily loss for the S&P 500 in excess of 3%. Over the past nine trading sessions, there have been losses of -3.4%, -3.0%, -4.6% and -3.4%. And Tuesday saw stocks fall nearly 3%, down 2.8% on the day.

Volatility is back in a big way but it doesn’t always work in the same direction. Monday saw the S&P 500 rise close to 5% in a single day. Wednesday the S&P was up more than 4%. This means 6 out of the past 9 trading sessions saw losses or gains in excess of 3%.

The current bout of volatility is likely some combination of the potential pandemic from the coronavirus and the shake-up in the Democratic primary. But there are other factors at play when stocks begin seeing such big moves with almost no memory from day-to-day.

Research shows that investors hold onto losing stocks too long in hopes they’ll come back to their original price while selling their winners too early. Recency bias and anchoring to recent results create a situation in which markets often underreact to initial news reports, events or data releases.

On the flip side, once things become apparent, investors enter a herd mentality and overreact, causing an overshoot to either the upside or downside. Fear, greed, overconfidence and the confirmation bias can lead investors to pile into winning areas of the market after they’ve risen or pile out after they’ve fallen, exacerbating moves in both directions.

These behavioral biases are all elements of human nature that exist in some form within all of us but they become amplified during a market rout.

The amygdala is the reflexive part of your brain that responds to danger and potential risks. It plays a role in shaping fear and anger. At times, this fear center in your brain acts as your own internal Spidey sense to keep you out of harm’s way. But the amygdala also becomes more active when we are losing money, switching on our fear center at a time when emotions are already on high alert.

In his book Your Money and Your Brain, Jason Zweig discusses how the fight or flight instinct is often triggered when people lose money:

A surge of signals from the amygdala can also trigger the release of adrenaline and other stress hormones, which have been found to “fuse” memories, making them more indelible. And an upsetting event can shock neurons in the amygdala into firing in synch for hours—even during sleep.

Zweig says, “It is literally true that we can relive our financial losses in our nightmares.” And because this fear center kicks in when there are big, quick changes, sudden market downturns can make a huge impact on how investors react to these things.

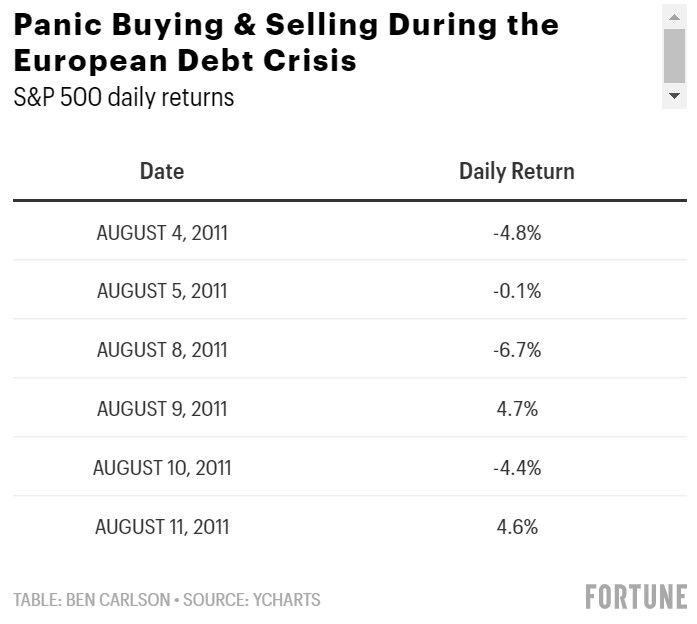

This fear can manifest itself in both panic selling and panic buying when volatility flares up in the markets. For instance, over a six-day period during the 2011 European debt crisis, the S&P 500 saw the following trading pattern:

There was no rational reason for stocks to rise and fall by more than 4% in 5 out of 6 trading days but stocks were in the midst of a double-digit correction and the Great Financial Crisis was still fresh in people’s minds.

So the types of market moves we’ve seen in recent weeks are nothing new. The question is: How do you prepare yourself as an investor to avoid financial nightmares from causing even greater pain in your portfolio?

Automate good decisions in advance. Automation can help people save more but it can also lead to better-informed investment decisions. Creating if/then investing parameters, rebalancing bands, asset allocation targets, and rules-based buy and sell decisions can help avoid making decisions under duress when your brain is not functioning at full speed. The fear response can be dampened if you make your investment decisions ahead of time.

Build losses into your investment plan. The stock market is up roughly 3 out of every 4 years but even when stocks go up in a given year, they always incur setbacks. To avoid overreacting you have to assume stocks can and will go down at some point, even if you don’t know the reason in advance or the magnitude of the losses.

Find an outlet. When volatility picks up it becomes tempting to overcompensate by paying more attention to the markets than usual or making more changes to your portfolio than you normally would. One way to avoid reacting to your fear center is by giving your brain a rest.

Go for a jog, take a hike or go for a walk. The amygdala also produces adrenaline so finding a way to channel that boost in energy can help make more level-headed decisions and avoid the stress that comes from losing money.

This piece was originally published at Fortune. Re-posted here with permission.