It feels like we’ve been having the same conversation about U.S. stock market valuations for 7-8 years now. But just saying “valuations are high so they have to come back down to average” misses out on the nuance and context required to think through where they stand.

It would be naive to assume valuations will stay elevated forever but it also makes sense to understand why they’re elevated in the first place. Here’s what I wrote for Fortune on the topic.

*******

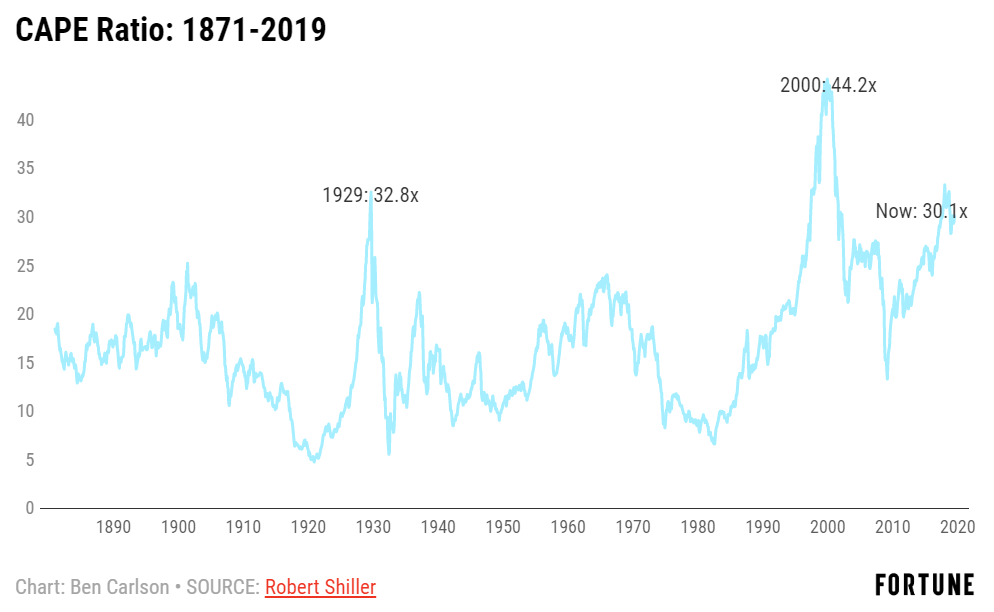

Robert Shiller’s cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio has only breached 30 three times in history.

The first time was in 1929, just a few short months before the stock market was trounced in one of the worst crashes in history during the Great Depression. Almost 70 years later, it happened again in 1997 and stayed above that level for nearly 5 years as the dot-com bubble deflated. The most recent flirtation with a CAPE of 30 began in the summer of 2017, where it has remained in a tight range ever since.

This could be a scary proposition for those who use market history as a guide. The Great Depression saw stocks fall almost 90%. After the CAPE reached 30 in the late-1990s, tech stocks continued to inflate the market bubble as the S&P 500 rose 85% but it was eventually chopped in half from 2000-2002.

Market valuations are an important input into the investing process. But the relationship between the markets and valuations is far from perfect and requires context when thinking about what sky-high valuations mean for today’s investor.

Interest rates and inflation matter

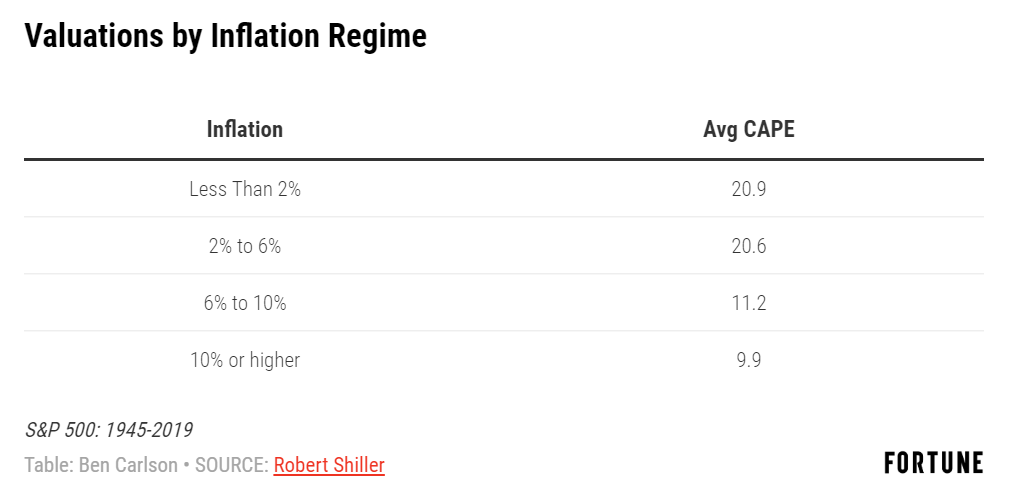

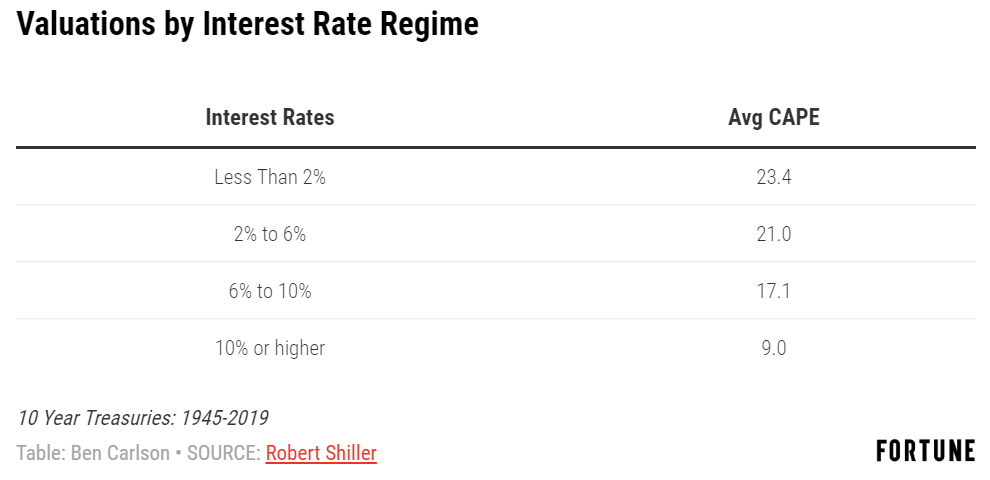

There is a case to be made that valuations should be higher these days because of the economic environment. Interest rates have been low for going on a decade now and inflation is basically non-existent. When interest rates and inflation are low, valuations tend to be higher.

This makes sense when you consider higher interest rates, and thus inflation makes for a higher hurdle rate for investing in the stock market. When rates and inflation are lower, that hurdle rate should also drop. This doesn’t mean valuations or stocks have to stay high, but if interest rates and inflation remain subdued, the stock market should have higher valuations attached to it.

The stock market is different

Professor Shiller’s data goes back to 1871 but much of it was pieced together from historical data that was created after the fact. The S&P 500 was actually only formed in 1957.

The original index was comprised of 425 industrial stocks, 60 utility names, and 15 railroads. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that financials were added to the mix. And it took until the late-1980s for Standard & Poors to adopt the current model that’s more diversified and amenable to the make-up of the economy.

Historical data is all we’ve got to understand how the stock market has functioned and performed over time but it’s always going to be an imperfect substitute for precisely understanding what’s going on in today’s landscape. Each environment is unique.

Setting expectations

Valuations can be helpful for setting reasonable expectations for investors because higher valuations typically lead to lower long-term returns while lower valuations typically lead to higher long-term returns.

Going back to 1926, the average 10-year return on the S&P 500 is roughly 10.4% per year. When the CAPE ratio was below 10, the average return jumps to more than 18% per year. But when the CAPE was 25 or higher, the average 10-year return falls to just 4.2% per year. So the fact that valuations are stretched today means investors should likely rein in their performance expectations.

However, it’s also worth noting the range of outcomes investors have experienced within overvalued markets. The worst 10-year return when the CAPE was above 25 was an annual loss of nearly 5% per year while the best 10-year return was 9.3% per year.

So even if valuations remain higher because the composition of the sectors in the stock market have changed or interest rates remain historically low, investors should still temper their expectations about expected long-term returns. Valuations are not a timing tool in terms of calling a market crash but they can help investors set reasonable expectations about the range of future outcomes.

This piece was originally published at Fortune. Re-posted here with permission.