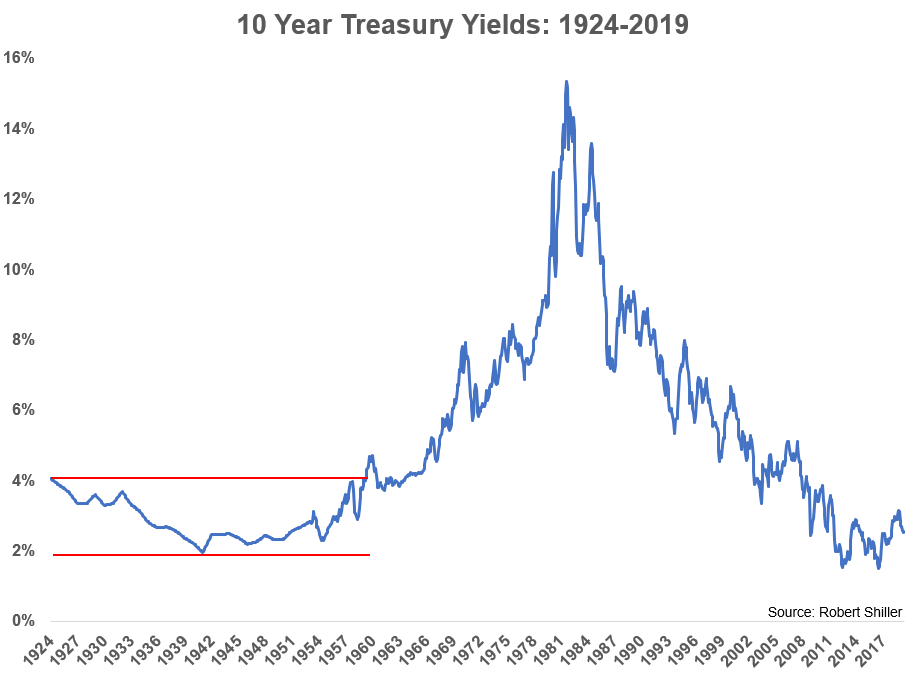

From 1924-1959, the 10-year treasury yield was stuck in a band from 2% to 4%:

That’s more than 35 years where interest rates basically went nowhere!

Granted, that’s a much different period in history. The country was still licking its wounds from World War I when it entered the roaring 20s, leading to the Great Depression, which was followed by World War II. Also, the markets were not nearly as mature back then as they are now.

Still, there is a precedent for an extended period of ultra-low interest rates for decades on end.

So the question to ponder is this: What if rates stay low for a long time?

More to the point, as my colleague Josh Brown posited in a recent post (with an assist from William Bernstein): What if the cost of capital never rises again?

Josh wrote a wonderful piece on this where he discussed what this has meant in the current environment in recent years:

There are no asset managers who represent their strategy to clients as “We buy the most expensive assets, and add to them as they rise in price and valuation.” That’s unfortunate, because this is the only strategy that could have possibly enabled an asset manager to outperform in the modern era. It’s one of those things you could never advertise, but had you done it, you’d have beaten everyone over the ten-year period since the market’s generational low.

But almost every investment professional says that they do the opposite of this. Even the explicitly growth-oriented managers use terms like “at a reasonable price,” to communicate their place on the spectrum of speculative chastity. There are no textbooks lauding an investment approach where it makes more sense to buy PayPal at 4 times book on its way to 9 times book while forsaking Goldman Sachs at less than 1 times book.

After reading Josh’s piece a number of questions immediately sprang to mind:

What happens to investment rules of thumb if this type of environment continues?

Would this potentially change how people invest their money?

Does this change the valuation profile for certain types of stocks?

Is Japan the best or worst case scenario here?

Howard Marks begins his latest memo with a story about legendary investor John Templeton. Templeton is probably most known by today’s investors for his quote that, “The four most dangerous words in investing are ‘This time it’s different.'”

Marks quotes a story from the New York Times published in 1987 where the author states:

Even Mr. Templeton concedes that when people say things are different, 20 percent of the time they are right.

I’m of the opinion that things are always and never different in the markets. It just depends on what you’re referring to.

Human nature is the one constant but the factors moving and controlling the markets beyond our emotions are constantly changing over time.

Obviously, no one knows if interest rates and inflation will remain subdued over the long haul. This is a thought experiment but one that can be helpful for investors to go through.

Listen to our full discussion here:

We discuss:

- What would an extended period of low-interest rates mean for the economy? Inflation?

- Do investors deserve to earn a high risk-free rate of return in a mature economy like the US?

- What would decades of low rates mean for cycles and valuations?

- Has technology disrupted inflation?

- How many companies are still alive today simply because the cost of capital is low?

- What would a bond investor do in a sustained period of low rates?

- What does this all mean for the consumer?

- Is it naive to assume rates and inflation will remain subdued?

You can read Josh’s post When Everything That Counts Can’t Be Counted.

Enable our Alexa skill and get start your day with The Compound Show.

Subscribe to the podcast on your favorite podcast app.

Further Reading:

What If Risk-Free Returns Slowly Go Away?