Morningstar’s John Rekenthaler shared a wild statistic about Yale’s endowment fund in a piece published yesterday:

The fund’s reputation, however, owes to its earlier accomplishments. In the 10 years from mid-2008 through mid-2018 (the latter being the date of the fund’s most recent report), Yale gained an annualized 7.4%. During that same time period, the three largest target-date 2035 mutual funds, from Vanguard, Fidelity, and T. Rowe Price, returned 7.3%, 6.7%, and 8.0%, respectively.

They underperformed the S&P 500 by close to 3% per year in this time.

I would not have predicted Joe 401k investor would have been able to keep up with one of the brightest, most sophisticated institutional investment offices in the world for a decade.

It would have been mind-boggling to suggest this would be possible when looking at the results from 2007. The trailing 10-year returns from fiscal year-end 2007 for Yale’s endowment were a staggering 17.8% per year, crushing every other fund or benchmark in its path.

Donations helped as well but these returns helped push the value of the fund from $5.8 billion to $22.5 billion in 10 years! The endowment is still massive at more than $29 billion as of fiscal year-end 2018, but the growth has obviously slowed.

Whenever I post these types of comparisons the peanut gallery always hits me with the usual caveats:

- Of course they underperformed the S&P — U.S. stocks have been the only game in town.

- Diversification hasn’t been rewarded over the past decade.

- But what about their risk-adjusted returns? Can you calculate the Sortino ratio for me?

- It doesn’t matter how they did against some arbitrary benchmark as long as they achieved their goals.

The last bullet point is the one I agree with the most but the other arguments don’t hold up.

The big college endowment portfolios look nothing like the typical public benchmarks so it’s not apples-to-apples to compare them.

But David Swensen himself, Yale’s CIO, wrote the following in Yale’s 2017 annual endowment report:

While Buffett appropriately recognizes the challenges investors face in manager selection—perhaps most notably that the vast majority of managers who attempt to outperform fail after taking into account fees and expenses—his conclusion goes too far. The superior results of Yale and a number of peers strongly suggest that active management can be a powerful tool for institutions that commit the resources to achieve superior, risk-adjusted investment results.

The results have been extraordinary, as demonstrated by Yale’s record. For the twenty-year period ending June 30, 2017, Yale produced a 12.1% return, outpacing the 7.5% return of the Wilshire 5000 Stock Index, the 6.9% return of a classic 60% U.S. equity and 40% U.S. bond portfolio, and the 5.2% return of the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index.

The results of the top ten performers amaze. Their well-diversified portfolios crush the returns produced by U.S. stocks, adding untold billions of dollars to support the educational missions of their institutions.

Swensen was defending the Yale model from those saying more institutional investors should index. And he compared Yale’s admittedly wonderful performance to the U.S. stock market and a 60/40 portfolio.

If you brag about your outperformance against public market benchmarks when things are good, you also own it when it’s bad. And those amazing 20-year numbers show how much the prior 10 year returns mattered considering the underperformance against U.S. stocks over the past 10 years.

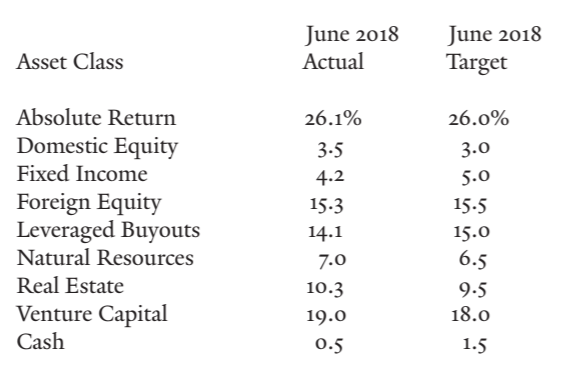

As of their last annual report, Yale has close to 80% of its fund in illiquid fund structures such as hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, natural resources, and private real estate:

They have the ability to accept illiquidity because of their long time horizon but in no way do these funds or asset classes exhibit lower volatility than the public markets.

These assets aren’t marked to market very often so the volatility is hidden. It’s basically Schrodinger’s portfolio. So any attempt to make “risk-adjusted” return comparisons is a fool’s errand. The numbers would be made up for the sake of a board report so everyone could slap each other on the back.

I actually do think comparing these funds to public equity markets is a better proxy than most for the simple fact that illiquid assets contain far more risk than a more liquid fund or ETF.

Private equity, hedge funds, and real estate employ leverage. It’s difficult to access your funds when you need them the most. If a fund shuts down it could take years to get your money back. And many private investments made by these funds are more like small-cap stocks overlaid with borrowed money than the larger S&P 500 companies. So even a 60/40 is far too conservative a comparison.

I say these things not to take anything away from David Swensen and his tenure at Yale. He is a hero of mine in the institutional investment community, and more for his ability to govern a fund and avoid the pitfalls of politics in the endowment world than his unbelievable track record.

And with the benefit of hindsight, it does make sense that Yale would struggle in the environment we’ve been in over the past 10 years. Maybe their previous 10 year returns simply came back to earth for some much-needed mean reversion. Maybe it’s harder to outperform with $30 billion.

But if I’m having a conversation with my 2008 self, that prior version of me would not have believed present-day Ben that David Swensen would be bested by a T. Rowe Price target date fund over the coming 10 years.

“Not a chance,” says 2008 Ben.

Nor would I bet against Swensen over the next 10 years. I agree with Rekanthaler’s conclusion:

The last time Yale’s endowment fund looked this out of sorts was the late 1990s, and it promptly posted outstanding relative results. Perhaps history will not repeat. But I would not bet against such an occurrence.

However, I do believe the insane amount of competition in the private markets, which Swensen is partly to blame for because of his immense success in that space and the book he wrote on the topic, does mean these college endowments are no longer as untouchable as they once were.

And hopefully, that’s a good thing for the institutional investment community, most of whom had no business trying to replicate Swensen’s success in the first place.

Further Reading:

6 Reasons For David Swensen’s Success at Yale