This week Fidelity became the first fund company to offer index funds — a total U.S. stock market fund and an international stock market fund — with an expense ratio of 0%.

Fidelity is a massive company that more or less missed the boat on index funds and ETFs when the first wave hit. This is surely an attempt to gain back some lost ground in the low-cost space and attract new clients.

As Bloomberg’s Eric Balchunas noted on Twitter, Fidelity’s annual revenue is around $18 billion. That’s 2x the revenue of the entire ETF industry and 4x the size of Vanguard’s revenue. So they can afford to be a loss leader in this space to attract new investors.

The move to zero may not seem like a big deal when you consider you can get similar funds or ETFs at Charles Schwab or Vanguard for 0.03% to 0.05% in fees. A couple basis points here or there isn’t going to move the needle if you’re simply trading down from one uber low-cost fund to another. When you include securities lending income, some of these funds are basically free anyways.

But the idea that you could gain access to such a large, diversified, indexed, group of corporations for free would likely have seemed insane just a few decades ago.

Charley Ellis recounts the history of the first index funds which came to market in the 1970s in his book The Index Revolution:

In the fall of 1974, Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson had written “Challenge to Judgment,”27 an article arguing that a passive portfolio would outperform a majority of active managers and pleading for a fund that would replicate the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 index. Two years later, in his regular Newsweek column, Samuelson reported, “Sooner than I expected, my explicit prayer has been answered” by the launch of the Bogle-LeBaron First Index Fund.

Samuelson notwithstanding, the First Index launch was not a success. Planned to raise $150 million, the offering raised less than 8 percent of that, collecting only $11,320,000. As a “load” fund, with an 8.5 percent sales charge, aiming to achieve only average performance, it could not gain traction. The fund then had performance problems. While outperforming over two-thirds of actively managed funds in its first five years, in the next few years it fell behind more than three-quarters of equity mutual funds. High fixed brokerage commissions were one problem. A larger problem came with “tracking” difficulties. To minimize costs, the portfolio did not own all the smaller-capitalization stocks in the S&P 500. Instead, it sampled the smaller stocks just as that group enjoyed an unusually strong run, so the fund failed to deliver on its “match the market” promise.

Renamed Vanguard Index 500 in 1980 and tracking the index closely, the fund grew to $100 million in 1982, but only because $58 million—more than half—came by merging into the fund another Vanguard fund “that had outlived its usefulness.” Finally, as index funds began to gain acceptance with some investors, the Vanguard fund reached $500 million in 1987.

So the very first retail index fund initially had an 8.5% sales charge, which is astronomical by today’s standards.

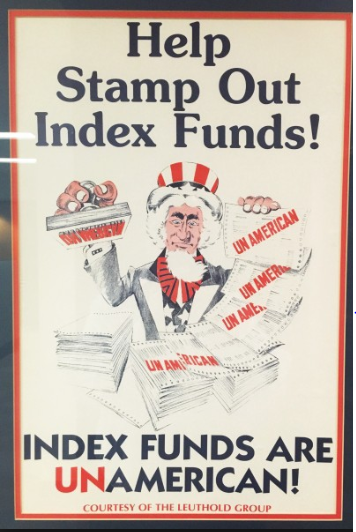

The idea wasn’t exactly a hit right off the bat with investment consumers or the fund industry. Supposedly, fund companies across the country began hanging this poster in their offices in 1977:

Plenty of ink has been spilled on the rise of index fund the past few years but here are a handful of big picture takeaways on how they’ve changed the markets and investing business since launching:

- Lower fees, narrower bid/ask spreads, and smaller transaction costs have freed investors from frictions they were forced to deal with in the past. Owning “the market” portfolio was cost-prohibitive in the past and quite complex to pull off. Investors of yore who were forced to call up their broker for stock tips or to make buys and sells would be unbelievably jealous of our ability to transact in seconds on our smartphone at no cost or hassle.

- It’s possible gross market returns will be lower going forward than they were in the past but the higher cost of doing business for previous generations means investors were earning far less on a net basis than the historical records show.

- The continued ease of access to invest in the overall stock market at such low costs likely has something to do with the fact that valuation multiples have been slowly rising over the past few decades. Convenience and cost-effectiveness have to play a role here, even if it’s hard to quantify precisely.

- Higher valuations and lower yields have made things difficult for investors trying to navigate today’s markets, but there has never been a better time to be an individual investor.

- The greatest friction in the markets remains our own brains of course. Behavior is the final frontier in a world where index funds are free. I don’t expect this to change anytime soon, even when the fund companies start paying you to invest in their funds (yes, this will happen at some point).

Source:

The Index Revolution

Now here’s what I’ve been reading this week:

- Appealing fictions (Collaborative Fund)

- Visually impaired cyclists get creative in coast-to-coast race (CBS News)

- 5 things that aren’t so predictable in the markets (Humble Dollar)

- “He was to finance what Shakespeare was to poetry and Michelangelo to art.” (Keith Akre)

- Morgan Housel on naked brands (David Perell)

- 4 lessons from the richest women in the history of Wall Street (Dollars and Data)

- Are index funds impacting price discovery in the stock market? (Irrelevant Investor)

- On the value of being proven incorrect (Abnormal Returns)

- Active management is difficult (Behavioural Investor)