Investors have a funny relationship with yield. Retirees tend to prefer an income-based strategy, even at the expense of total returns. Plenty of investors (and politicians) have a poor understanding of share buybacks. Another area of confusing stems from making yield comparisons across stocks and bonds. You could certainly make the case for comparing bond yields to stocks in terms of expected returns in the asset allocation decision but comparing bond yields to dividend yields makes little sense. This piece I wrote for Bloomberg makes the case that measuring stock and bond yields against one another is not an apples-to-apples comparison.

*******

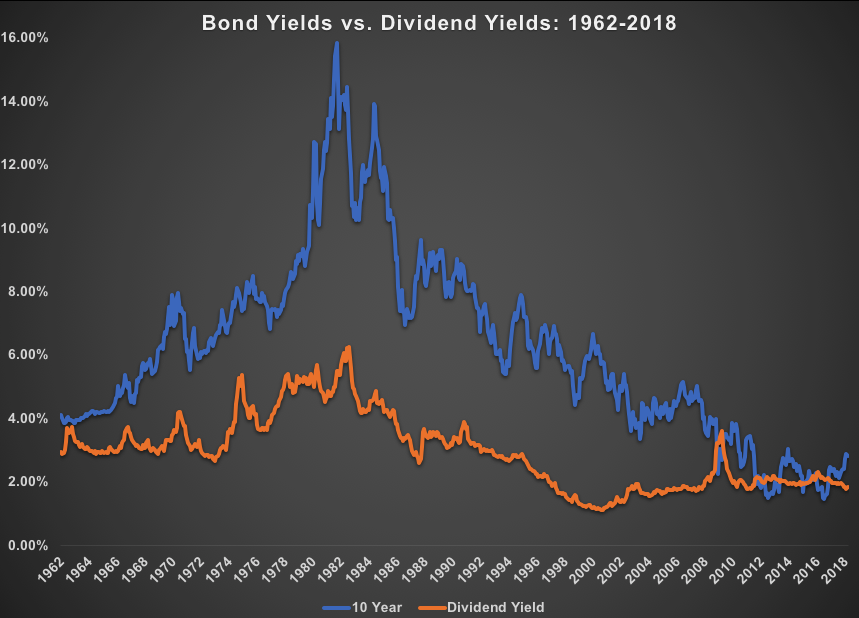

The 10-year Treasury yield has been on a tear in recent months, rising from just above 2 percent to almost 2.9 percent since last fall. The surge accounts for a divergence between bond yields and dividend yields on the stock market. The dividend yield on the S&P 500 is roughly 1.8 percent, so the 10-year now yields more than 100 basis points more than stocks. From an asset allocation perspective, this has led to concern that bonds now offer legitimate competition to stocks for the first time in a number of years.

Rising interest rates typically don’t have a negative impact on stock market returns, but with yields being so low for so long, it’s certainly possible this could cause a psychological shift in investor sentiment, especially considering the magnitude of the move up in stocks during this cycle.

But there’s more that goes into this analysis than a simple comparison of yield levels. Although this is the first time since 2013 this spread has been more than 1 percent, bonds have yielded more than stocks for some time now going back to the 1960s. The average spread of bond yields to dividend yields going back to 1962 has been well over 3 percent.

Before the 1950s it was commonplace for stocks to yield more than bonds because corporations needed to entice investors to put money into equities through a juicy dividend yield. That relationship has evolved over the years, as bond yields have been higher than dividend yields for some time now. It was only in recent years that stocks briefly yielded more than bonds.

Bond yields are fairly straightforward, but dividend yields on stocks are not. Stocks and bonds differ in a number of ways, from how they’re structured to their risk and return profiles. But they also differ in terms of how they act as a source of income. A bond security has a set interest rate that pays out a specific periodic income payment based on the initial yield and principal value.1

Stocks don’t have a preset yield level. It fluctuates, and dividends can always be raised or lowered, but historically dividends have provided investors with a source of inflation protection over time. Dividends are one of the most stable aspects of investing in the stock market over the long term.

The volatility of the change in dividends from month to month is about one-fifth of the volatility of stock market returns in this time. With bonds, unless you’re investing in inflation-protected securities, there is no change in the amount you’re paid from the income of the bond — hence the name “fixed income.” But dividend yields have shown impressive growth rates over time.

Using data from Yale University’s Robert Shiller, I looked at the growth rate in dividends going back to 1900. Dividends compounded over this time frame at 4.7 percent annually. Those numbers have been even more impressive in recent decades. From 1945 to 2017, the growth in dividends was 6.1 percent per year. Even from the peak of the market in early 2000 before the dot-com bubble crash, dividends have risen 6.2 percent annually. That’s even better than the 5.3 percent annual return on the S&P 500 in that time.

Dividends have also held up relatively well during market downturns. According to Shiller, the stock market fell more than 80 percent on a real basis during the Great Depression, but inflation-adjusted dividend levels were down just 11 percent. When stocks got chopped in half during the brutal 1973-74 bear market, dividends fell just 6 percent in that time. And since the 1960s, the annual rate of growth on dividends has never been negative over all rolling five-year periods.

Rising or stable dividend payments offer little solace during a stock market crash or correction because you always have to look at total returns in these instances. Bonds will likely offer much greater protection from volatility than stocks in these situations.

But bond yields can’t be compared to dividend yields on an absolute basis. Dividends offer the potential for long-term growth in income payments, but looking at dividends alone doesn’t tell the entire story for stock market yields. You also have to consider share repurchases and debt repayments by corporations, both of which make stock market yields look more attractive when seen through the lens of a shareholder yield approach.

Investors like to understand what their portfolios look like from a yield perspective to gain a better understanding of their income potential for future returns. For bonds, this is a simple framework for setting future return expectations. For stocks, it’s not quite that simple because there are far more variables in the yield equation than meet the eye when just looking at the dividend yield on the market.

1This is the case for the majority of bonds but there are exceptions such as TIPS.

Originally published on Bloomberg View in 2018. Reprinted with permission. The opinions expressed are those of the author.