When we have success in our lives we tend to attribute that success to skill or hard work. When something goes wrong and we fail, we attribute it to bad luck.

Sound familiar?

I know I do this all the time. It’s easier than admitting that there was some luck involved in our wins and a lack of skill in our losses. This is called the self-serving attribution bias.

In business, investing or life it’s tough to distinguish luck from skill. That’s what Michael Mauboussin tried to do in his excellent book, The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports and Investing.

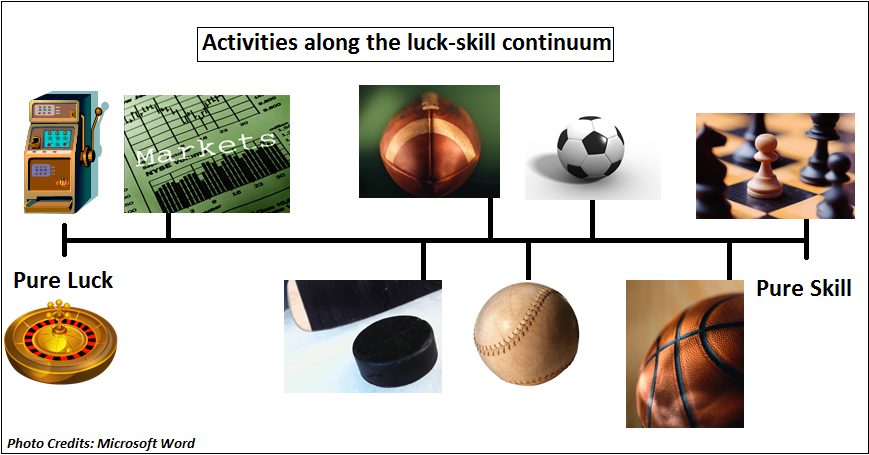

One of the most interesting aspects of this book is how Mauboussin weaves seamlessly through the worlds of business, investing and sports. He has a chart in the book which I recreated below to show where certain activities fall on the scale of luck and skill.

These are based on statistical analysis and are only his estimates from the historical data. But they all make sense when you consider his logic.

On one side (pure luck) you have gambling. The odds are in favor of the house, so even if you have some sort of strategy when playing roulette or the slot machines, based on the probabilities, large wins are driven by luck. You can’t lose on purpose playing the slots, so it’s based on pure luck.

On the other side (pure skill), you have chess. This game takes many, many hours or even years to master and it would be very difficult to beat a skillful opponent through luck alone. You can lose chess on purpose, so you know there is skill involved.

For the most part, skill for professional sports over a season can be determined by the number of possessions that a team gets over the course of a game.

NBA teams have a large number of possessions, so it is technically the game most affected by skill. That’s why the team with the best player usually wins the title (think about how many of the NBA’s best all-time players like LeBron, Kobe, Jordan, Magic, Bird and Russell have won multiple titles). Over the course of a season, 90% of a team’s performance in the NBA is explained by skill.

The other sports are clustered together with football and hockey falling closer to the luck side because there are fewer possessions. This makes sense since we do tend to see unexpected teams win the title in the NHL and NFL.

You’ll notice that investing actually falls fairly close to the luck side of the equation. This is not because investing is entirely random or similar to pulling the handle on a slot machine.

We know that investing involves a great deal of luck, because there aren’t experts who can consistently forecast where the markets are going. That means that many short-term market calls involve a lot of luck.

Of course, as Mauboussin points out in the book:

There is a difference between saying that the short-term results of investment managers are mostly luck and saying they are all luck. Research shows that most active managers generate returns above their benchmark on a gross basis, but that those excess returns are offset by fees, leaving investors with net returns below those of the benchmark.

That means that there are really only a small number of investors that have the skill to create returns over and above the fees that are paid. That’s why costs are so important to your overall performance.

There is also greater reversion to the mean in activities that involve luck. One study in the book looked at mutual funds ranked in the top quartile for performance in 1990s. They outperformed handily in that decade so the study wanted to see if those returns would persist.

In the 2000s, the top quartile funds suffered a 7.8% decline in relative performance while the bottom quartile funds showed a 7.8% rise in relative performance. I’d say that describes mean reversion perfectly.

This doesn’t mean that you simply give up and leave all activities that have a large element of luck in them up to chance.

You just have to think long-term and use probabilities to your advantage. Here’s Mauboussin on how to change your luck:

For activities near the luck side of the continuum, a good process is the surest path to success in the long run.

This makes sense but you have to be patient with a long-term process and use discipline.

Especially when investing, doing well in the short-term doesn’t really tell you much about your skill because you can have the perfect analysis or reasons for your decisions and the markets can still go against you. Or you could take a flier on a stock for no reason and it takes off and gives you a huge gain.

In that scenario, which investor will have more success over the long-term? The one with the rational process, of course. The more times you try your hand at luck, the higher your chance for loss.

But come up with a process that has a high probability for success over multiple time frames and you should come out on top in the end, even if you have setbacks over shorter periods of time. That’s how successful long-term investing works.

One of my favorite concepts in this book is the paradox of skill, which means that as the participants gets better at an activity, luck plays a more important role in determining who wins. This is such an interesting concept that I’m going to write a follow-up post about how this relates to your investment options.

This book has completely changed the way I view skill and luck in determining success, so it definitely gets my stamp of approval. One of the best books I’ve read this year.

Source:

The Success Equation

[…] investors are getting much better. Michael Mauboussin termed this the paradox of skill in his book, The Success Equation (which is also where I got the Ted Williams information). So as skill improves, performance becomes […]

[…] STRATEGIES Here’s a funny story from The Success Equation about the “skill” involved in winning the lottery by a man in […]

[…] Seek out alternative opinions. Metacognition (big word I just learned) means that the less competent you are at a task, the more likely you are to over-estimate your ability to accomplish it. Actually having competence in a given field reduces self-confidence. Knowing your limitations and admitting that you could be wrong or don’t know what’s going to happen next can help reign in the overconfidence in your investing abilities. This is very important when markets are rising and investors mistake luck for skill. […]

[…] Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman The Success Equation by Michael Mauboussin The Behavior Gap by Carl Richards The Coffeehouse Investor by Bill Schulteis […]

[…] up being right usually have a healthy dose of luck involved. As Michael Mauboussin pointed out in The Success Equation, it’s very difficult to separate luck from skill in the investment […]

[…] Michael Mauboussin has an interesting test to see if there’s any skill involved in an activity (versus being mostly luck). Basically, if you can lose on purpose, then there has to be some skill involved. […]

[…] Reading: Do You Feel Lucky? My Letter to Young […]