A few years ago I attended an institutional investment conference headlined by John Paulson, the man who became famous following the real estate crash for the greatest trade ever. While Paulson is known for shorting sub-prime mortgages he actually specialized in merger arbitrage before tackling the macro hedge fund world.

Merger arb is a strategy that seeks to profit from announced corporate takeovers or mergers. When a merger date and price are announced the stock will typically trade at a discount to that price in the event that something causes the deal to fall through. Merger arb investors seek to make money by buying the discounted stock and shorting the company doing the takeover to profit from the narrowing of that spread. Sprinkle in some leverage and you can make some money if you know what you’re doing.

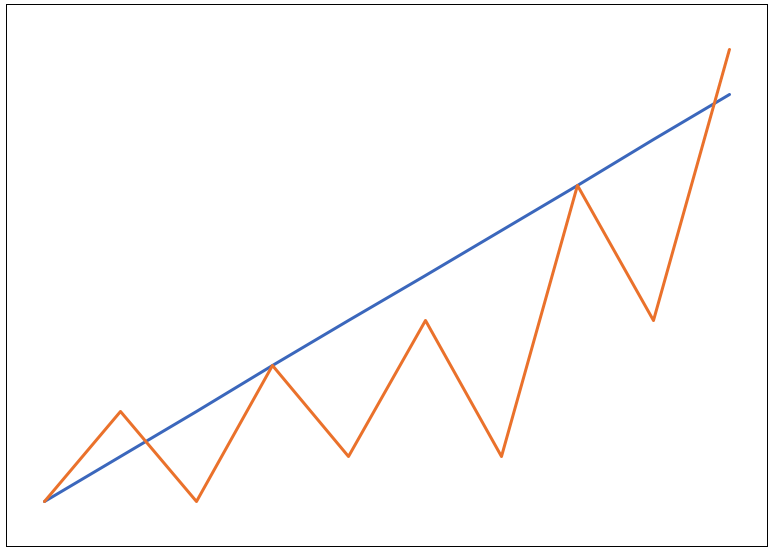

During Paulson’s speech he was describing the virtues of this strategy and put up a graph that looked something like this:

In this example, the blue line would be the merger arb strategy and the orange line would be the stock market. I’m exaggerating here but the general point he was trying to make was that merger arb is very much a low volatility way to invest in the market. He was predicting an uptick in volatility in the stock market and urging people to invest in the safety of his merger arb fund.

I was reminded of Paulson’s talk this week when I read about the struggles his merger arb fund has been going through (courtesy of the New York Times):

But it has not been smooth sailing. In another letter to investors of a merger arbitrage fund that declined by 49 percent last year, Mr. Paulson called 2016 “the most challenging year since inception.” In May, Mr. Paulson will address his investors at a meeting at Claridge’s Hotel in London.

Mr. Paulson’s fall from stock-trading stardom underscores a common disclaimer in industry parlance: Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

The strategy that Paulson described as giving investors much lower volatility than the stock market fell almost 50% in 2016, a year in which stocks rose double digits. Arbitrage has been described as earning a “riskless” profit but risk never completely goes away in the markets — it just changes form.

*******

At an event held a few years earlier by the same conference organizers, I got to hear GMO’s Jeremy Grantham give his thoughts on the state of the markets. He was none too optimistic, to say the least. Grantham talked about how profit margins and valuations on the market were far too out of whack from the historical equilibrium. His thesis was that the reversion to the mean would see both stocks and profit margins fall from such great heights. He has been writing about this in his quarterly letters for GMO for a number of years now.

In an interview with Wealth Management last week, it seems like Grantham walked back some of these ideas:

The market was extremely well-behaved from 1935 until 2000. It was an orderly world in which to be a value manager: there was mean reversion. If a value manager was patient, he was in heaven. The market outperformed when it was it cheap, and when it got expensive, it cracked.

Since 2000, it’s become much more complicated. The rules have shifted. We used to say that this time is never different. I think what has happened from 2000 until today is a challenge to that. Since 1998, price-earnings ratios have averaged 60 percent higher than the prior 50 years, and profit margins have averaged 20 to 30 percent higher. That’s a powerful double whammy.

With value investing and mean reversion, you have to be careful with saying this time is never different. Things do change. I was really lucky in that the first 30 years of my career were similar to the prior 30 years. But 1997 was very bad preparation for the next 20 years.

[Value] investors have overweighted the past. The Fed [easing] represents a regime change. That’s perhaps the most powerful change in my career.

Certain investors hate this phrase but he’s essentially saying that it’s different this time. And it is because it’s different every time.

Relationships change. Corporations and industries evolve. Historical averages and equilibriums are not set in stone.

I give Grantham credit for coming to this realization (something he has done before) but I wonder how his investors feel about it after years of playing the mean reversion waiting game.

My goal here is not to rub salt in the wounds of Paulson and Grantham. They’ve have been wrong in recent years but both have made really great calls in the past. That’s how it works when you try to make bold market predictions.

I think what happened is they got stuck in the past. Paulson was looking to prove his subprime bet was no fluke while Grantham was looking to cement his legacy as an expert on market bubbles. Unfortunately, I think they were experts on the way things used to work.

Tech investor Paul Graham wrote about this idea in 2014 but it has stuck with me ever since:

If the world were static, we could have monotonically increasing confidence in our beliefs. The more (and more varied) experience a belief survived, the less likely it would be false. Most people implicitly believe something like this about their opinions. And they’re justified in doing so with opinions about things that don’t change much, like human nature. But you can’t trust your opinions in the same way about things that change, which could include practically everything else.

When experts are wrong, it’s often because they’re experts on an earlier version of the world.

At times, being an expert can actually be a limitation if it blinds you to the fact that things are changing all around you. Graham summed it up this way:

It’s hard enough already not to become the prisoner of your own expertise, but it will only get harder, because change is accelerating. That’s not a recent trend; change has been accelerating since the paleolithic era. Ideas beget ideas. I don’t expect that to change. But I could be wrong.

With such rapid change, it’s becoming harder for investors to understand which historical rules they should follow and which ones were simply useful in an earlier version of the world.

Sources:

How To Be An Expert in a Changing World (Paul Graham)

John Paulson’s Fall From Hedge Fund Grace (NYT)

Grantham: The Rules Have Changed for Value Investors (Wealth Management)

Further Reading:

Macro is Hard