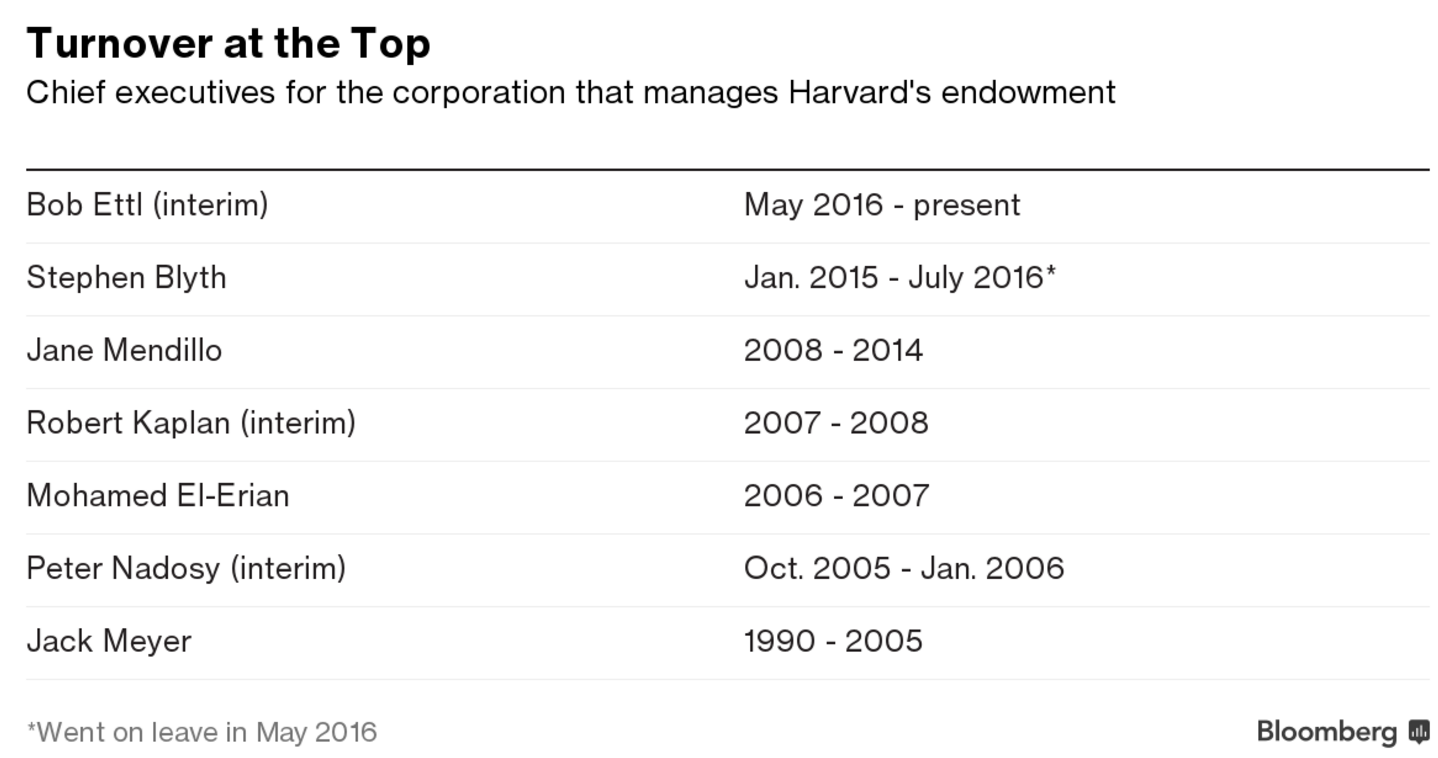

The Harvard Management Corp., which oversees the management of the school’s endowment fund, recently lost yet another CEO. The list of ex-Harvard endowment CEOs is growing longer by the year:

Harvard’s current interim chief marks the sixth person to lead the endowment since Jack Meyer left in the mid-2000s, good enough for an average tenure of just under two years. The latest attempt at a turnaround in strategy, which is still fairly new, will also have to be unwound (via Bloomberg):

After years of missteps, controversy and even crisis, Harvard Management Corp., which oversees the university’s $37.6 billion endowment, began assembling a new corps of equity traders and analysts in 2014, in hopes of recapturing a part of the investment magic that had once made the fund the envy of the world.

Only now, just two years later, that plan has collapsed. Stephen Blyth, 48, the former bond trader behind that effort, stepped down as HMC’s chief executive Wednesday for personal reasons after just 18 months on the job. His resignation follows the departure in June of Michael Ryan and Robert Howard, the two former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. partners he had brought in to guide the new equity strategy.

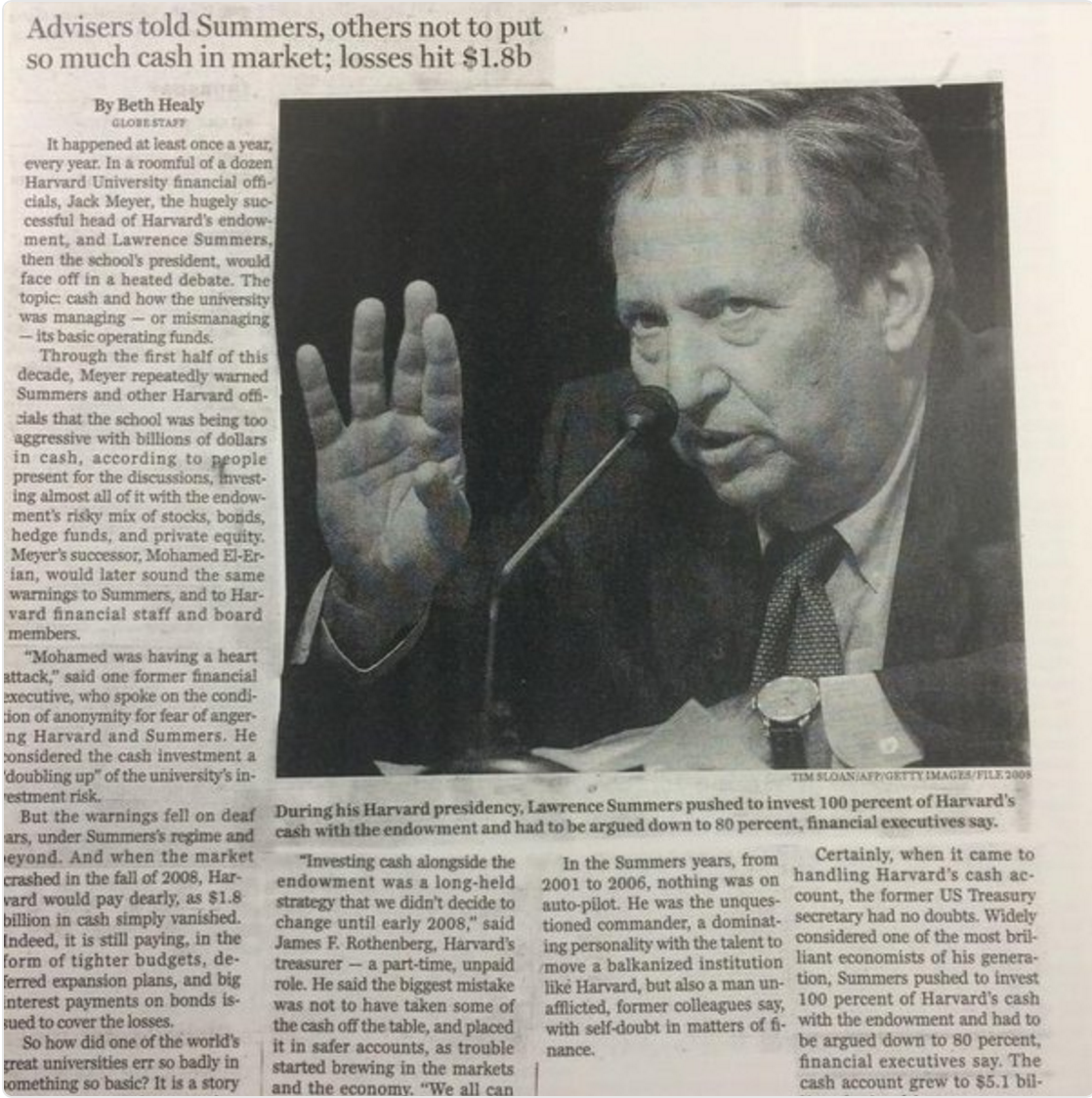

Harvard has had a difficult go of it since Meyer was more or less forced out because people within the university were concerned about the pay of his staff (which forced him to start his own hedge fund and make even more money through fees paid by the university). The financial crisis was a difficult one as well:

Add all of these problems up and it still probably won’t matter for Harvard. They still have $37 billion. They still bring in millions of dollars every year from wealthy donors. They’ll still be able to attract talented individuals to manage their money for them. Don’t shed any tears for poor Harvard. They’ll be fine.

The Harvard’s of the world want to be “best in class” in everything they do. Trying out all of these different complex approaches to investment management is something they’re never going to shy away from, regardless of the potential problems it can create. They have a permanent capital base that will likely grow regardless of their investment performance because so many alumni want to get their names on the buildings.

But individuals or smaller institutional investors who aren’t Harvard don’t have the luxury of running a lab experiment every few years to try something new. Making these types of changes on a regular basis can be a killer for those that don’t have forever money to play with.

There can be enormous costs along the way when you constantly change your strategy and leadership:

- Switching Costs: There are frictions and costs every time you make sweeping portfolio changes like this. These costs are amplified when dealing with illiquid investments in things like private equity, venture capital, real estate and hard assets. But perhaps the biggest cost when making wholesale portfolio shifts is a lack of understanding by the investors, board members and beneficiaries, which really opens the door for mistakes down the line. No investment process can survive a lack of understanding.

- Staff Turnover: Leadership is something of an intangible asset that’s not easily quantifiable, but having the right people in the right places can be a huge advantage when managing money on other people’s behalf. It’s not easy to have a clear direction in place when you have staff turnover, changes in committee members or a constant stream of new leaders in an organization. These changes all take a toll.

- The Decision-Making Gap: Group decision-making can be difficult in a university endowment setting because you’re dealing with so many conflicting ideas, personalities and egos. This becomes almost impossible when no one really knows who to listen to or they don’t trust the person at the helm. Add in changing investment philosophies, strategies and staff and it can make it nearly impossible to make well-informed long-term decisions.

Long-term partnerships are extremely underrated in a finance industry that seems to value action and the new-new thing over continuity and partnerships. You have to put in a lot more time upfront when building lasting relationships with trusted partners, but it’s worth it in the end because it can save you from unnecessary internal and external costs along the way

Harvard has access to more intellectual and financial capital than 99.9% of investors on the planet. And they’re still having a hard time getting their act together. With $37 billion I think they’ll survive. For everyone else, there’s something to be said for an approach that favors durability and continuity over complexity and excitement.

Source:

The Unraveling of Harvard’s Star Trading Desk (Bloomberg)

Further Reading:

The Importance of Continuity in Portfolio Management