Lee Child spent nearly 20 years of his career working in television.

Then he got laid off.

With no fallback plan, he started writing a novel about an ex-military cop named Reacher who traveled from town to town cleaning up ruffians with nothing but a toothbrush and the clothes on his back.

He’s now written nearly 30 books1 in the Reacher series which has spawned two movies2 and a TV show.

Child was interviewed on the Art of Manliness podcast recently and talked about the importance of starting as a writer later in life (he was 39):

A successful writing career is almost always a second phase career because it is good to wait till you’re older. Writing is wonderful from that point of view. Your first career, whatever it was, has had all kinds of ins and outs and problems and highs and lows. That teaches you something so that by the time you are in the middle of your life, you’re ready. You’ve got gas in the tank. You’ve got ideas stored up. I think it’s really difficult to write when you’re young.

Mick Herron is another author who got a late jump on writing. Herron had a day job as an editor for a trade publication but wrote for an hour when he got home from the office. His goal was just 350 words a night.

His spy series, Slough House, was a slow burn, taking years to become a smash hit. Now the books have sold millions of copies, and Slow Horses is in its fourth season on Apple TV. For my money, it’s the best show on TV right now that no one talks about.

Herron told The Wall Street Journal he too was glad his success as an author came later in life:

“The main lesson I’ve taken away from this is that if you’re only going to be successful in one half of your career, make it the second half,” Herron said. “If it’s the first half, that’s a tragedy. But the second half is a happy ending.”

The Economist highlighted a new study about Michelin-star restaurants that opened in New York between 2000 and 2014, which also received a glowing review in the New York Times.

That sounds like an envious position for the notoriously competitive restaurant industry. Nope.

By the end of 2019, 40% of these restaurants had closed their doors for good. In fact, restaurants that received the prestigious Michelin star were more likely to close than the establishments that didn’t obtain that status.

The Economist explains:

A Michelin star boosts publicity: the study found that Google search intensity rose by over a third for newly starred restaurants. But that fame comes at a price. First, Mr Sands argues, the restaurants’ customers change. Being in the limelight raises diners’ expectations and brings in tourists from farther away. Meeting guests’ greater demands piles on new costs. Second, the award puts a star-shaped target on the restaurants’ back. Businesses they deal with, such as ingredient suppliers and landlords, use the opportunity to charge more. Chefs, too, want their salaries to reflect the accolade and are more likely to be poached by competitors.

This is basically the same reason lottery winners are more likely to go bankrupt.

Success can be a blessing and a curse.

The person who dutifully saves money over 30-40 years has time to slowly but surely become acclimated with their wealth over time. Pulling forward that success and becoming wealthy overnight can play mind games with you because you’re the same person but now you have all these other pressures that come with instant wealth.

The same is true of fame and even economic volatility.

For instance, The Wall Street Journal has a new piece about how the inflation rate is back to normal but people are still seething about price levels:

“It’s hard to adjust,” said Marilyn Huang, a 54-year-old engineer in Doylestown, Pa.

As with many Americans, Huang’s pay has increased since 2020, and she and her partner continue to spend on travel and even dine out more than in the past. But the higher prices are aggravating.

“You lived with these stable prices for all your life,” she said. “Mentally, it’s hard.”

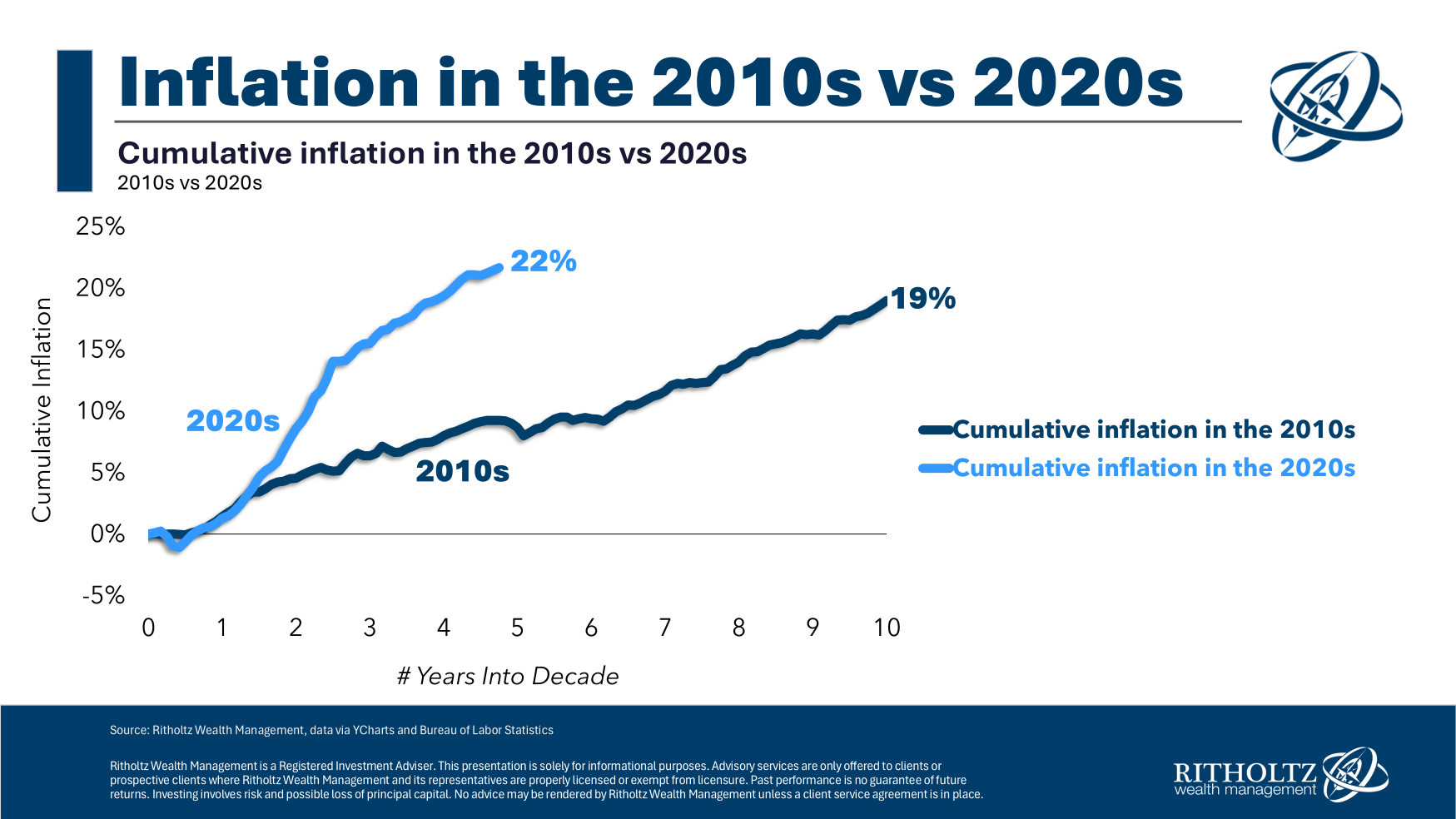

Of course, prices have never been stable. It’s just that the inflation in the 2020s has happened in a much more compressed manner than people are used to:

Cumulative inflation the 2010s was 19%, pretty close to the cumulative inflation in the 2020s (so far). It’s just that the 2020s inflation came in a hurry so people were unable to get used to the new price points gradually.

The cumulative inflation in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s were 64%, 34% and 28%, respectively. Prices are almost always rising. Sometimes they just rise faster than others.

One reason inflation has been so painful to many households, not just financially but psychologically, is that we aren’t used to this kind of economic volatility in such a short period of time.

It’s never fun to live through these periods of upheaval but the good news is it’s building some muscle-memory. The next time economic volatility presents itself more people will be prepared.

Further Reading:

Overnight Millionaires

1I’ve read something like 27 of these books. They’ve finally started to lose some steam but it’s been a hell of a run.

2A rare miss for my guy Tom Cruise. The movies were decent but he was never right for the part.