Agriculture was invented approximately 10,000 years ago.

It’s estimated there were roughly 5 million people on Earth at the time.

This shift completely changed our species from nomadic hunter-gathers which allowed humans to live in larger and larger groups of people.

The population grew slowly but steadily from there reaching 1 billion people by the year 1800.

The average life expectancy in 1800 was just 30, mainly because of poor child mortality. Up until that point, almost half of all babies that had ever been born had died during childbirth. Four out of six children died before becoming parents themselves.

People had to have a lot of kids back then because (a) the majority of the population still worked on a farm so they needed the help and (b) so many of their children died at a young age.

Then the industrial revolution happened and the population exploded.

Hans Rosling provides what happened next:

Then something happened. The next billion were added in only 130 years. And another 5 billion were added in under 100 years. Of course people get worried when they see such a steep increase, and they know the planet has limited resources. It sure looks like it’s just increasing, and at a very high speed.

This massive increase in population has caused many a Malthusian to worry about scarce resources over the years.

So far things have worked out pretty good from that perspective especially when you consider we have nearly 7 billion more people on the planet now than 200+ years ago.

Now the worry is starting to shift in the other direction.

Instead of concern about overpopulation, many are becoming alarmed about declining fertility rates.

In 1948, women still gave birth to an average of 5 children. Starting in the 1960s, that number started dropping like a rock. Today the average is now well below two in most developed countries.

The Wall Street Journal had a feature this week that dug into the numbers:

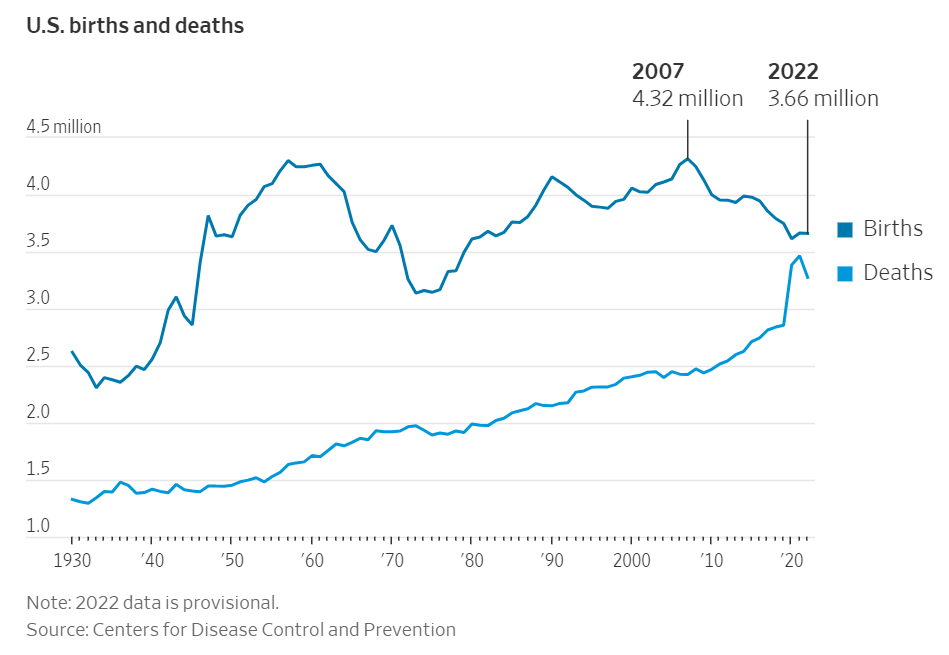

The government tallied about 655,000 fewer births in 2022 than the 2007 high of 4.32 million, reflecting ongoing decreases. With still-elevated deaths due in part to the latter phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, the U.S. in 2022 saw only about 385,000 more births than deaths.

The annual number of births and deaths in the U.S. are now almost equal:

The Covid spike had a lot to do with that but birth rates are falling.

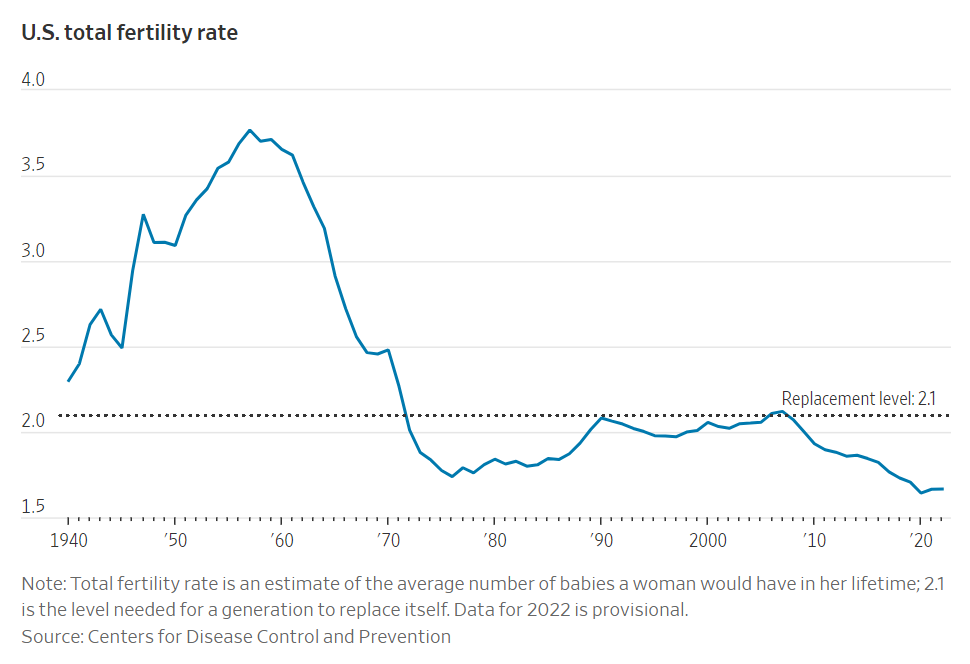

The fertility rate continues to fall as well:

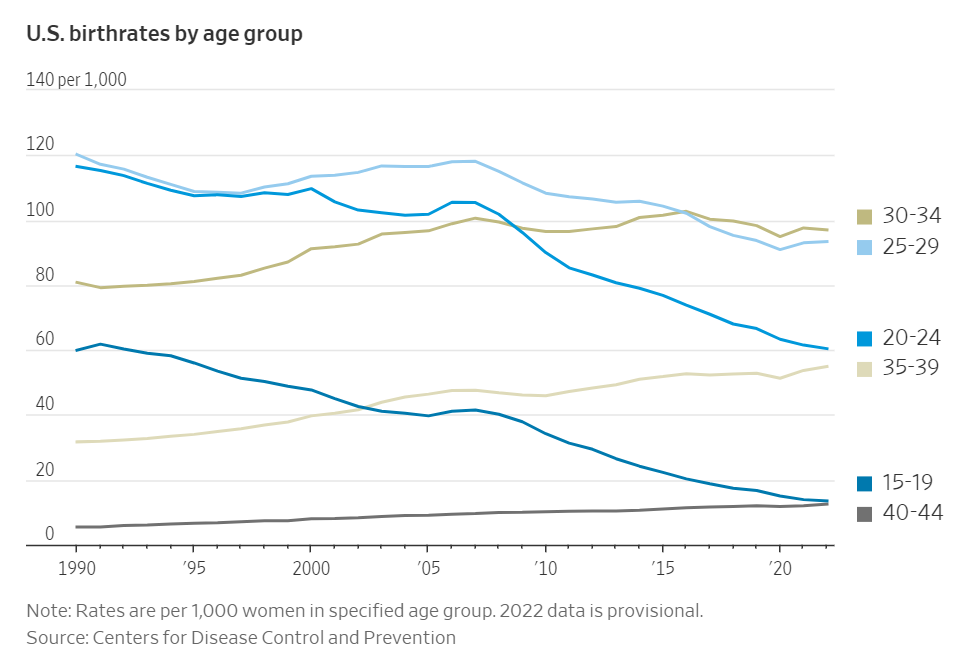

And people are waiting longer to have kids as you can see from the increase in the 35-39 and 40-44 cohorts (although it’s nice to see the decline in teen birth rates):

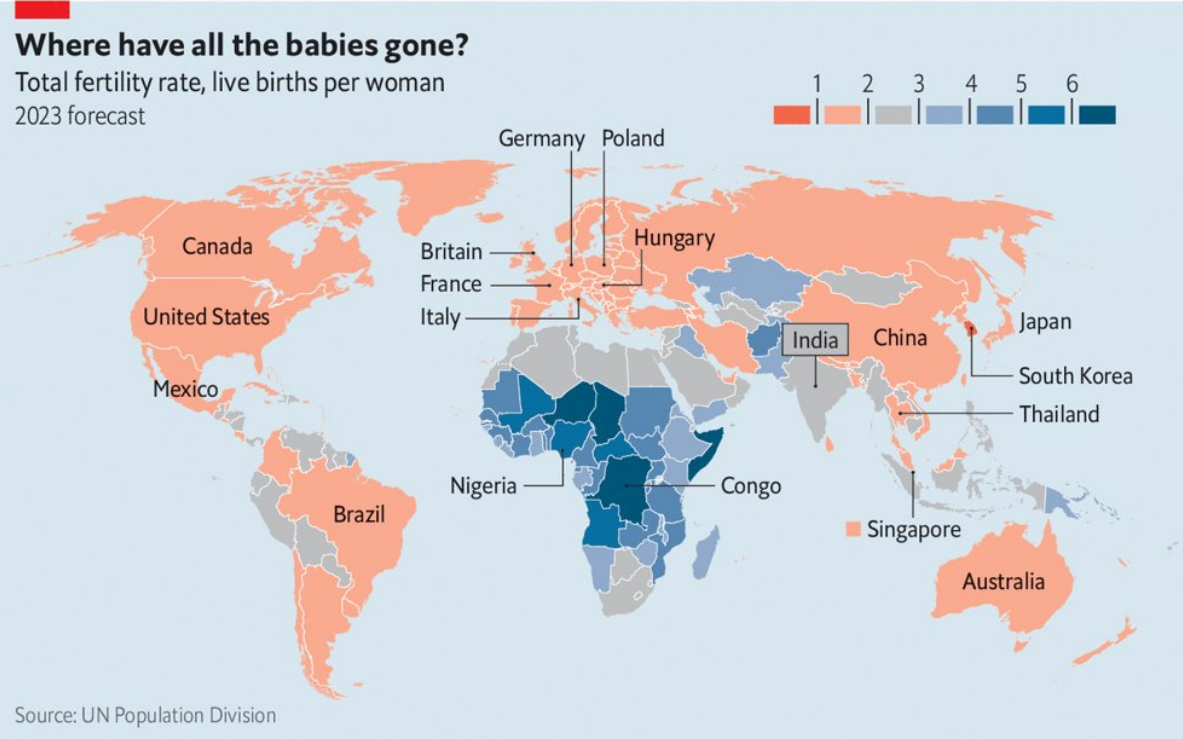

This is not just a U.S. phenomenon.

The Economist looked at global fertility rates and developed countries around the world are all fairly low relative to history:

It’s really only Africa and many other emerging markets that still have much higher birth rates.

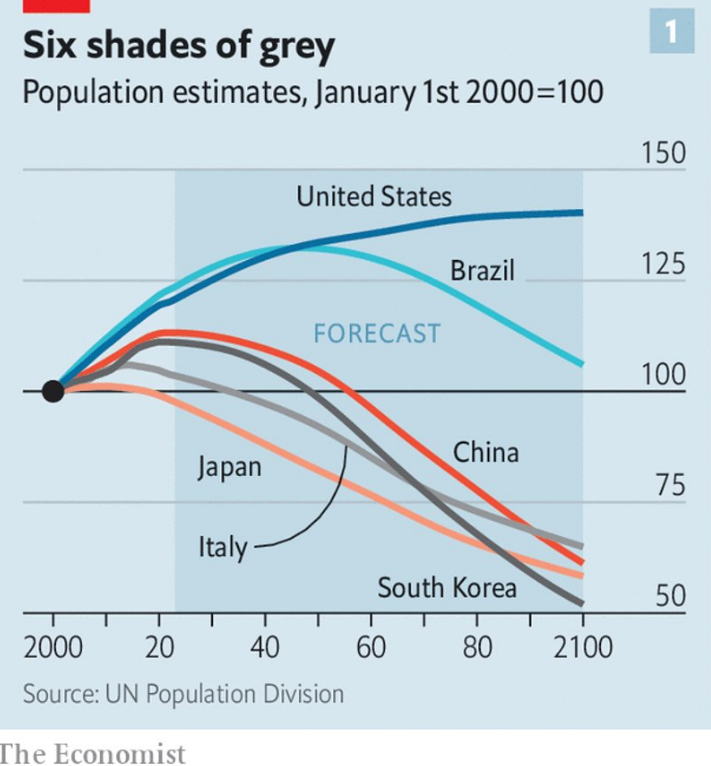

And look at the population estimates for some of the biggest countries in the world over the remainder of the century:

I’m guessing the only reason the United States is still rising is because of immigration. Japan, China, Italy and South Korea are all estimated to see their populations crash in the coming decades.

So why are people worried about this?

Well, there are really two ways to increase economic growth: (1) population growth and (2) productivity increases.

If the population begins to stagnate because of falling fertility rates, we could face some serious headwinds in the future when it comes to GDP growth.

There are a few reasons I’m not ready to sound the alarm just yet because of a baby bust.

The UN estimates we’ll still be adding another 3 billion people or so over the rest of the 21st century, taking the global population to roughly 11 billion.

How is this possible with declining fertility rates?

Life expectancy is projected to increase from a combination of old people living longer and fewer children dying at a young age.

It also makes sense that people are having fewer children as society becomes wealthier.

The poorest 10% of households around the world are still having 5 children on average. Many of these families still lose young children to death and disease.

The fact that so many people are having fewer babies these days is a sign of progress.

Two hundred years ago, 85% of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty and 80% of the population worked on a farm. Today those numbers are more like 9% and 4% globally.

People are more educated than ever. As child mortality falls and people earn more money, the fertility rate probably should go down.

Does this mean much lower rates of economic growth going forward?

It’s possible.

But I tend to believe a more educated workforce, combined with continued innovation (maybe AI can save us?) will make everyone more productive.

We figured out how to make enough resources available for 8 billion people.

I’m hopeful we can figure out how to deal with slowing population growth as well.

We are an adaptive species.

Michael and I talked demographics (he’s not worried yet either) on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

50 Ways the World is Getting Better