Investors are constantly in search of historical analogs when it comes to the various market cycles.

It makes us feel more confident in our investment stance if we have some semblance of an idea about how things could play out.

No two market environments are ever the same but there are always some similarities because human nature is the one constant across all cycles.

The 2020-2022 market environment has some eerie similarities to the dot-com bubble and bust of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

In each boom you had tech stocks going vertical, IPOs galore, the rise of day-trading, a retail investor renaissance, rampant speculative behavior, Warren Buffett getting mocked and people getting rich in a hurry.

In each bust you had tech stocks getting crushed, speculative securities falling 70-90%, retail volume drying up, Warren Buffett mounting a comeback, value stocks coming back in vogue and investors getting a reminder that making money is not always easy.

The Nasdaq fell nearly 80% from the dot-com bubble highs while the current bear market has seen it fall just shy of 30%. Maybe it has much further to fall but the overall market has seen nowhere near the damage of the dot-com blow-up.

The pandemic throws a monkey wrench into this analog though because the economy is in a far weirder place now than it was in the 1990s. The best historical example I can come up with for the current economic set-up is the post-WWII period.

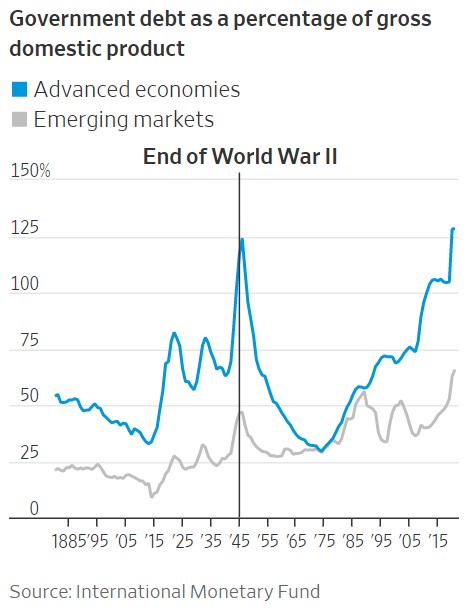

Both the war and the pandemic saw unprecedented government spending:

Following the war, there were all kinds of supply chain issues. There weren’t nearly enough homes built following the Great Depression for all of the soldiers coming home that wanted to settle down.

Plus, you had companies like Ford and GM that were helping with the manufacturing of tools, equipment and supplies for the war who then had to reverse course and get back to their prior business of making automobiles.

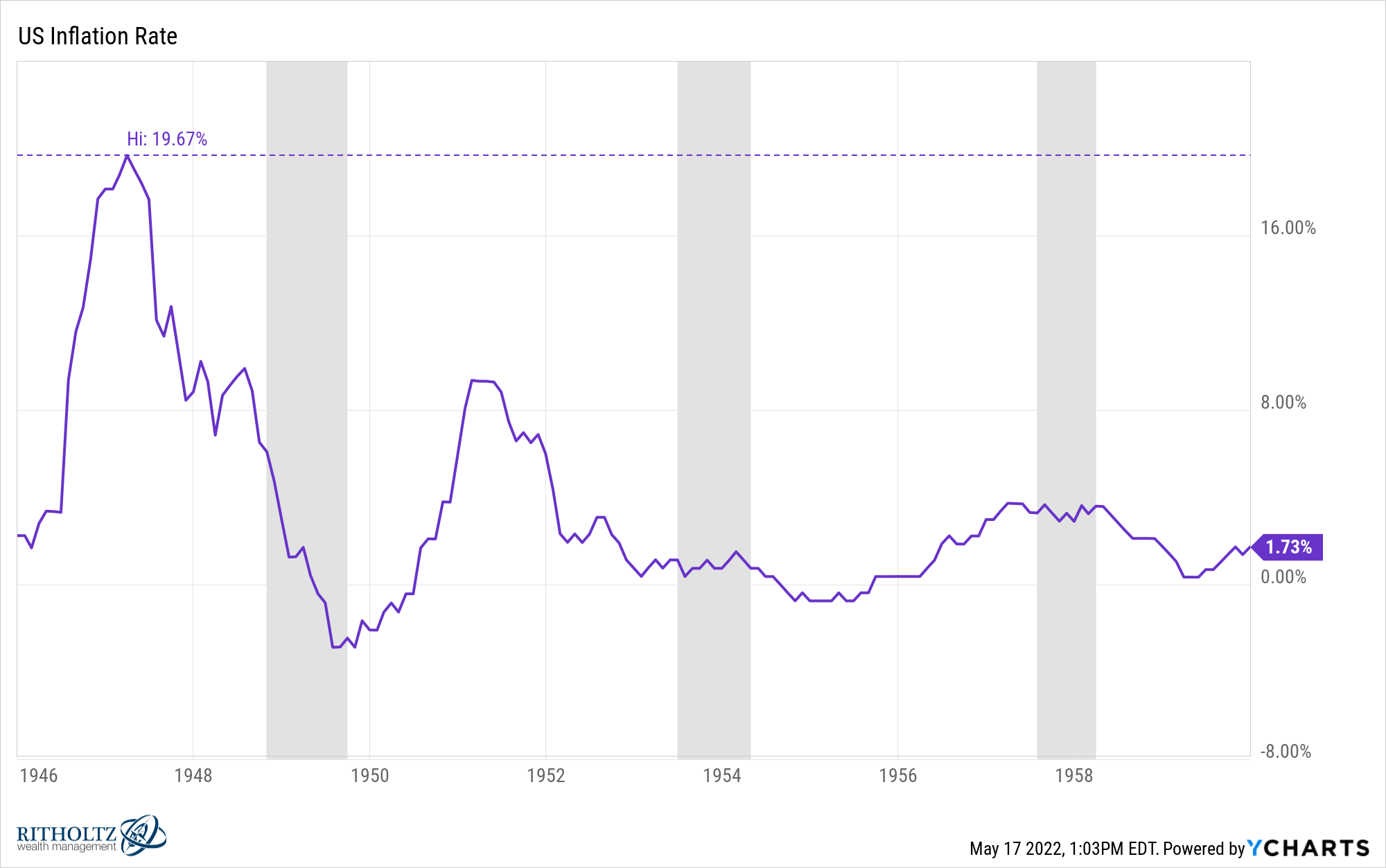

That combination of supply chain disruption and wartime government spending along with consumers consuming led to a massive surge in prices:

By 1947, inflation was running at nearly 20% on a year-over-year basis. That was followed by a shallow 11-month recession that began in 1948 which saw GDP fall 1.7%. That took the economy from inflation to deflation by the end of the decade.

Then in the early-1950s, there was another bout of inflation from the Korean war that saw prices increase nearly 10% per year. This mini-boom was followed by a 10-month recession where GDP contracted 2.6%.

By 1954, the Fed Funds Rate was less than 1%, still rather accommodative, and they became worried about the possibility of inflation picking up. From 1954 to 1957, the Fed raised rates from 0.75% to 3.5%. Tighter monetary policy caused another minor recession that lasted 8 months with GDP falling 3.7%.

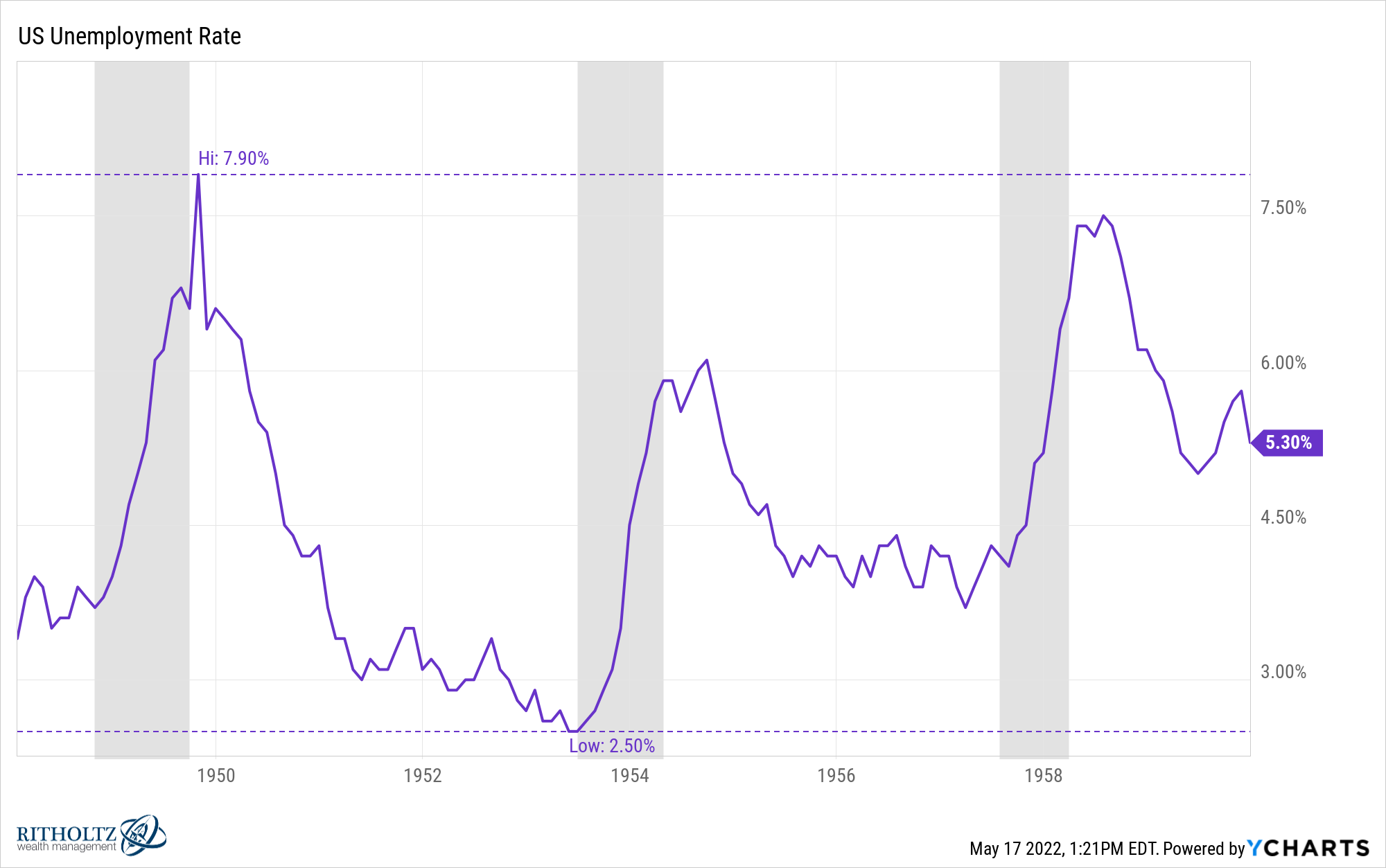

The unemployment rate fluctuated with economic activity but it never reached double-digit levels:

In fact, the lowest unemployment rate in history was printed in 1953 just before the recession began.

The post-WWII economy is generally seen as one of the biggest booms in our country’s history. We saw the rise of the middle class, high wage growth, the build-out of the suburbs, new housing galore and one of the most underappreciated bull markets in history.

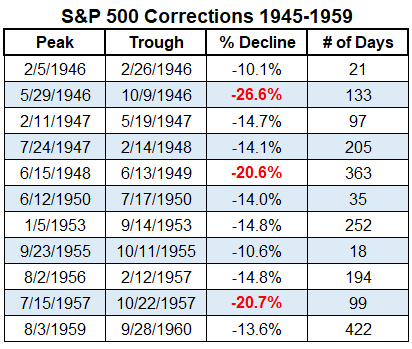

From 1945-1959, the U.S. stock market was up almost 900% or more than 16% per year. But there were plenty of corrections and even a handful of bear markets along the way:

So despite two inflationary spikes, three recessions and eleven stock market corrections, the country experienced one of the biggest booms in history.

Now, I’m not saying we are setting up for a similar run.

There are plenty of differences between these two periods as well.

The point here is recessions don’t always have to mean the world is coming to an end. Sometimes the U.S. economy just needs a pit stop.

Every time inflation spikes it doesn’t mean it has to be a repeat of the 1970s or the onset of hyperinflation. Sometimes all it takes is a minor recession to reset prices.

And every time the Fed tightens monetary policy it doesn’t mean the economy is going to collapse. Sometimes interest rates need to rise from emergency levels to normalize the economy.

Look, I don’t have the ability to predict what comes next with the economy, inflation or the Fed. The $23 trillion U.S. economy is so big and dynamic that it’s nearly impossible to forecast what will happen using a handful of economic indicators.

Recessions aren’t great because people lose their jobs, businesses go under and people lose some money.

But economic contractions are a feature, not a bug of the system in which we all participate.

In many ways, recessions are a necessary evil to shake out some excesses.

Michael and I were on Plain English with Derek Thompson again this week talking about the implications of a recession and more: