I talked with a group of financial advisors in recent weeks about retirement planning and one of the topics that kept coming up was sequence of return risk.

This is basically the idea that you if experience poor returns or a huge bear market when withdrawing your capital during retirement it could throw off your plans.

One of the reasons this risk is so difficult to prepare for is because it’s more or less based on luck. So much of this depends on timing, both good and bad, in terms of when you begin drawing down your money.

You could have been lucky by retiring in 2010 right before the onset of a decade-long bull market. Or you could have been unlucky by retiring in 2000 just before a lost decade of stock market returns which included two enormous market crashes.

It’s also important to remember it’s not so much the overall market return that matters with sequence of return risk but the order in which you receive those returns.

For example, from 2000-2020, the S&P 500 returned 6.6% annually.

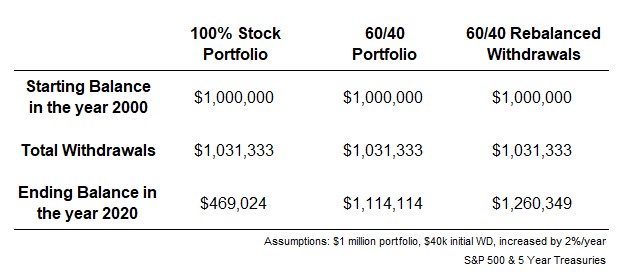

Let’s say you retired with $1 million in the S&P at the outset of the 21st century. And let’s further assume you decided to withdraw $40,000 in year one with an annual 2% inflation kicker each year thereafter.

By 2020, you would have withdrawn more than $1 million from that portfolio over 21 year period, while the remaining balance would still be just over $470k.

That’s not bad but it’s also not great depending on how much time you have remaining in retirement.

These were the annual returns for the S&P 500 during that time:

You can see the nasty bear market at the outset here, with stocks falling 37% from 2000-2002.

To show how sequence of return risk manifests itself, let’s assume our hypothetical retiree with a $1 million portfolio experienced these same exact returns but they occurred in reverse order. So the first year would be +18.4%, then +31.5% and so on.

The same $1 million or so would have been taken out as distributions but now there would be well over $2.3 million remaining.

The annual returns for the market would be the exact same in both examples — 6.6% per year. But the ending balances show a difference of close to $1.9 million.

How is this possible?

Luck, basically.

In the first example, that nasty bear market from 2000-2002 hit right as our retiree starting drawing down their portfolio. Not only was the market value of the account falling in each of those 3 years, but they were selling at a loss along the way.

In the reverse sequence, that bear market occurred at the end of the period while stocks rose in 11 out of the first 12 years.

The problem facing investors is no one knows in advance whether they’ll have good luck or bad luck on the timing of their retirement. A bear market at the outset could severely dampen your ability to spend while a bull market could actually improve your standing and give you more money than you ever could have planned for.

So how do you protect yourself in the event you experience bad luck from sequence of return risk?

Diversification. My example here was fairly crude. Few retirees have their portfolio entirely in the stock market.

Let’s add some bonds to the mix to see how an anchor in the portfolio would have helped in this situation.

Using the same assumptions as above, but this time instituting a 60/40 portfolio consisting of the S&P 500 and 5 year treasury bonds, would have left this retiree with more than $1.1 million by 2020 as opposed to the $470k under the all-stock portfolio.

The reason for this is simple — bonds provided diversification benefit by hedging the down years in the stock market.

Instead of losses of -9.1%, -11.9% and -22.1% in an all stock portfolio in 2000, 2001 and 2002, a 60/40 portfolio was down -0.4%, -4.1% and -8.1%, respectively.

By spreading your bets, you can reduce the risk of one asset causing severe damage.

Rebalancing. While the S&P 500 was up 6.6% per year from 2000-2020, 5 year treasuries returned a respectable 4.8% annually. However, a 60/40 portfolio of the two assets, rebalanced annually, would have resulted in a return of 6.5% per year, not much worse than an all-stock allocation.

The reason for this is a combination of diversification and rebalancing.

When taking distributions from a portfolio, you can intelligently rebalance your portfolio to avoid selling any assets that are experiencing losses or relatively poor gains.

Let’s assume instead of pulling money from both stocks and bonds in their 60/40 proportions (as we did in the last example), instead you intelligently rebalance based on the performance of each asset class.

In a relatively good year for the stock market, you take your distribution from stocks, and in a relatively good year for bonds, you take your distribution from bonds.

Now you ended up with almost $1.3 million by 2020, having still spent more than $1 million.1

Simply adding another asset class and intelligently rebalancing would have improved your ending value by more almost $800k in this example.

Have a financial plan in place. So far I’ve only given examples of rules-based investment decisions that could reduce the risk of bad luck during retirement. I could go through dozens of other investment strategies using specific backtests that could improve your results even more.

The perfect portfolio only exists in hindsight and every retiree is going to face unique market, spending, tax and withdrawal circumstances.

Therefore, the best and simplest way to hedge sequence of return risk is to have a flexible financial plan that allows for the occasional course correction.

While a comprehensive financial plan is important no matter your stage in life, it carries even more weight when you’re retired. At this stage in life you simply don’t have as much time or human capital to make up for poor market conditions.

So you must be able to adjust your plan to the reality of what the markets or your life throw at you.

That could mean holding enough cash or bonds to see you through a prolonged bear market or recession so you don’t become a forced seller in a down stock market. Or it could mean setting aside reserves when the markets are rocking to see you through the tough times on the other side.

However you decide to invest your money during retirement, a financial plan that takes into account the element of luck, both good and bad, is a necessity.

Further Reading:

What If You Retire At a Stock Market Peak

1It is worth noting you also wouldn’t end up with as much money when stocks knock it out of the park but we’re talking about reducing risk here so there is some balance required.