Some ideas are fleeting and go in one AirPod and out the other.

Others just seem to stick for some reason and you’re constantly coming back to them over and over.

Paul Graham wrote such an idea in 2014 about how to be an expert in a changing world and it’s stuck with me ever since:

If the world were static, we could have monotonically increasing confidence in our beliefs. The more (and more varied) experience a belief survived, the less likely it would be false. Most people implicitly believe something like this about their opinions. And they’re justified in doing so with opinions about things that don’t change much, like human nature. But you can’t trust your opinions in the same way about things that change, which could include practically everything else.

When experts are wrong, it’s often because they’re experts on an earlier version of the world.

The world of finance is littered with people who are experts on an earlier version of the world. They rely exclusively on specific backtests, formulas and strategies that would have worked wonderfully in the past.

Now, I’m not saying we can’t use history to help guide our actions in the markets but so many investors get stuck in the mindset of fighting the last war that they fail to realize things have changed to such a degree that the old playbook needs to be thrown out the window.

There are a handful of investment principles that are evergreen but the market structure is constantly in a state of flux. Companies, the market environment, sectors and the macroeconomy are never static so investing like they are can be problematic.

A handful of fund managers were lauded for calling the financial crisis of 2008 but they all but missed the subsequent recovery and bull market because they became fixated on a crisis mindset. In fact, the star fund manager is either extinct since 2008 or in deep hibernation.

One of the reasons this is the case is because so many professional investors were using a pre-2008 playbook. They assumed the Fed was going to cause massive inflation or a bubble from low interest rates.

Interest rates had never been so low for so long and investors were adhering to strategies that worked in the 1980s or 1990s but weren’t useful anymore.

We could be setting up for a similar paradigm shift following the events of 2020. In the future it’s possible we look back at the pandemic as a turning point in the use of government spending as a tool to counteract economic contractions.

Pseudonymous financial thinker extraordinaire Jesse Livermore wrote a detailed research piece on the potential for a new fiscal policy regime and how it could lead to upside-down markets:

But people on both sides of the aisle are increasingly coming to realize that fiscal policy is the “cheat code” of economics. If you’re willing to tolerate inflation risk, you can use it to achieve any nominal outcome that you want. As people become more aware of this fact, they’re going to increasingly challenge traditional approaches, demanding that fiscal policy be used to safeguard expansions and eliminate downturns. Upside-down markets will then become the norm.

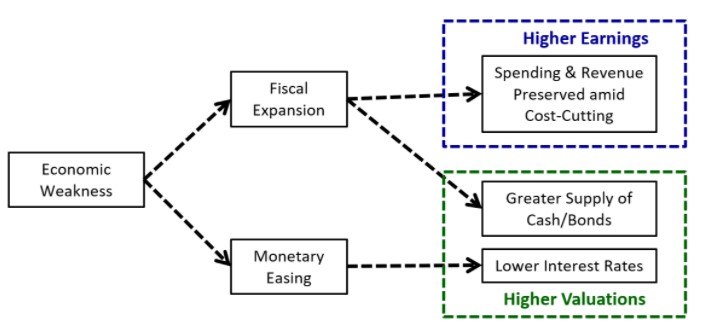

One of the most confusing aspects of the 2020 market environment to many investors is how such an awful economic backdrop could lead to such strong equity markets. Livermore provided a simple illustration to explain:

The basic idea here is with enough fiscal and monetary firepower, even the worst of economic environments can actually lead to higher prices in financial assets because investors know corporations have a backstop. And that’s exactly what’s transpired this year.

The government and the Fed stopped a depression by throwing gobs of money at it and investors looked across the valley because they knew it would be short-lived.

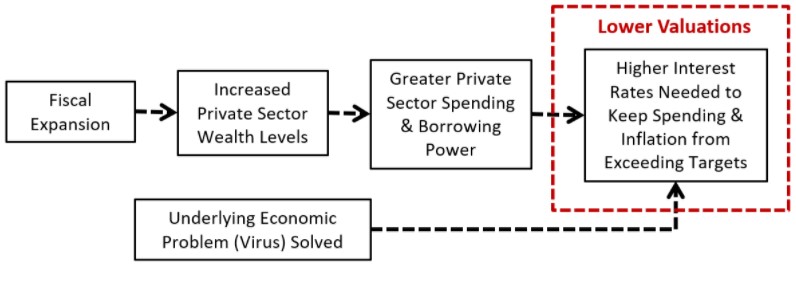

This strategy does come with its risks, inflation being the biggest one:

Inflation is not something we’ve had to worry about for some time now, so the downside risks from this new world could be significant.

Risk is funny like that. Take one off the table and another magically appears.

No one can be sure if 2020 was a fiscal fork in the road. It depends on what the political will for this type of spending will look like. I can’t imagine politicians who wouldn’t pull these levers in the future after witnessing their power but I’ve given up trying to figure out why politicians don’t use more common sense so you never know.

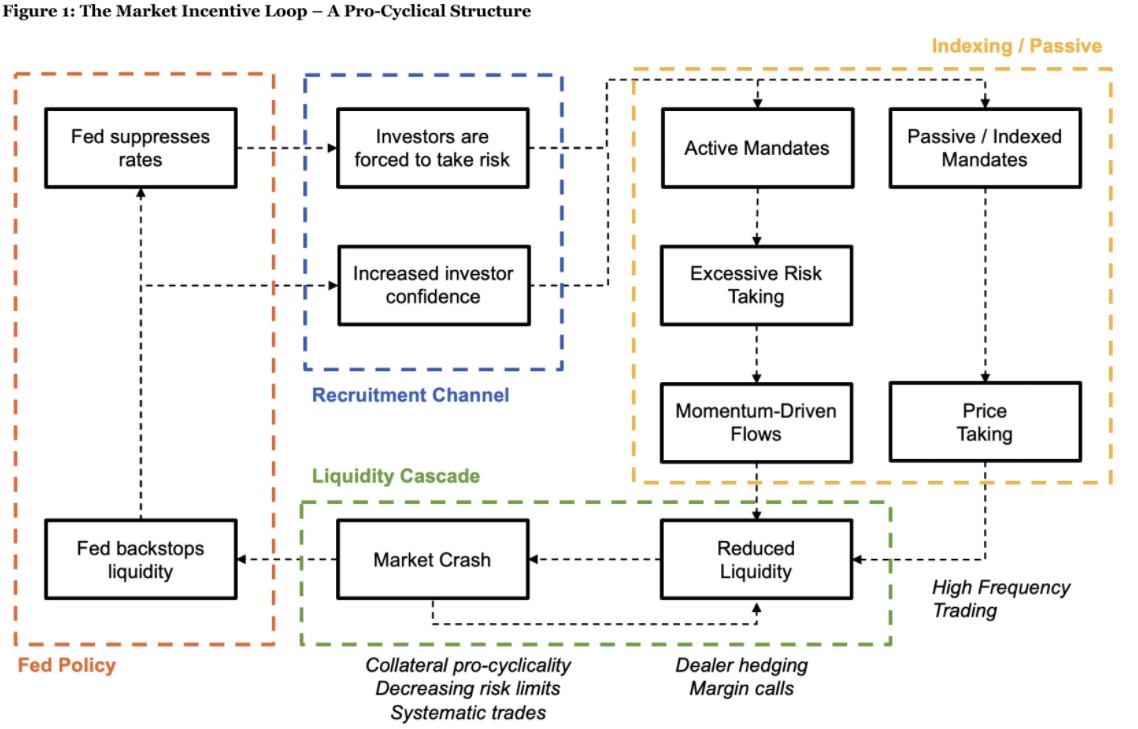

Corey Hoffstein also wrote a detailed description of market dynamics this week on liquidity cascades which came with its own illustration:

Hoffstein laid out the case that large, sudden bursts of market volatility are a product of central banking policies, the way people invest these days and the vehicles investors use to express their market views.

He makes a good case that we could see more volatility flare-ups in the future because of this.

You can never be certain about these shifts but Hoffstein and Livermore each make strong arguments for the changing nature of the market and the way investors should think about them going forward.

Understanding these potential shifts doesn’t make it any easier to predict the future because investor reactions to market dynamics are not static either.

But if you’re an expert on an earlier version of the world, you will likely continue to struggle in the ever-changing investment landscape.

I’m long open-mindedness in the coming years.

Further Reading: