There is always going to be a good reason to sell out of the stock market.

When stocks were getting slaughtered in March, investors wondered if they should sell because it felt obvious stocks would fall further.

Now that stocks have rallied, investors are wondering if they should sell because it feels obvious stocks have risen too far, too fast.

Those who actually sold a few months ago near the bottom of the bear market are in a much tougher position than those who are considering selling out now but anytime you make a wholesale shift in your asset allocation it’s a challenging decision.

These types of decisions become even more taxing when you’re in or approaching retirement. At that stage your human capital is dwindling and you don’t have nearly as much time to wait out the painful bear markets as younger investors.

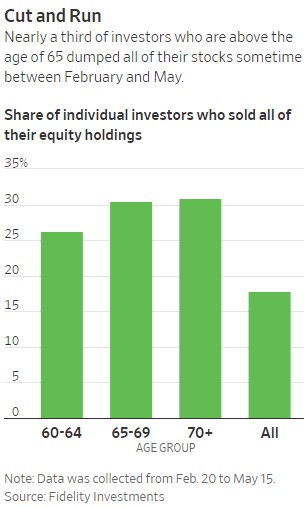

According to Fidelity and the Wall Street Journal, it appears older investors were more likely to sell during this bear market than younger investors:

Fidelity data shows nearly one-third of their investors 65 and older sold all of their stock holdings at some point between February and May while just 18% of all investors across their platform sold out of stocks.

I had a number of discussions with investors who were contemplating selling out of stocks in March. Many we retirees who worried about how an extended downturn could impact their retirement plans.

I understand why this group is more trigger happy with their portfolio. The U.S. stock market was up 10 out of 11 years heading into 2020. This crisis was looking like it could turn into Great Depression 2.0.

We’re living in scary times.

But scary times and panic are never good reasons for selling out of your stocks. Selling out and waiting for the dust to settle is also a horrible plan. Even valuations are close to useless as a timing indicator for the stock market as anyone who has traded based purely on fundamentals the past 20-30 years can attest.

A bear market is one of the worst times to completely overhaul your asset allocation because your decision-making ability will be clouded by your emotions.

So when should you sell some or all of your stocks?

When you need to rebalance. The all-in or all-out game is one of the most dangerous you can play when investing. Sure, you could luck out once or twice but eventually you’re going to end up selling out before a huge boom or buying before a huge bust.

Unless you have a rules-based approach that you follow come hell or high water, an extreme strategy like this will cause you to make a huge mistake at the worst possible time.

The simplest form of selling comes when you have a target asset allocation in mind and religiously rebalance back to your target weights on a set schedule or pre-determined threshold.

After stocks were up more than 30% in 2019 that would have resulted in selling some of your stocks to buy more bonds, cash or other investments following a big run-up in prices. And after stocks dropped more than 30% in the spring and bonds acted as a ballast to a diversified portfolio, that would have meant selling some of your fixed income and buying more stocks. Now that stocks have risen 40%…you get the picture.

The timing of a rebalance will never be perfect but setting up a specific asset allocation that takes into account your willingness, ability and need to take risk removes the temptation to go all-in or all-out based on your gut instincts and sell based on a set plan.

When you need to diversify. I know a number of investors who kept the majority of their retirement assets in the stock market in lieu of bonds for their entire accumulation phase. This strategy is not for the faint of heart but when you’re a net saver with a high tolerance for short-term financial pain, the results can be wonderful when you stay the course.

Once that accumulation phase is over and the transition into the distribution phase of retirement begins, this introduces a new dynamic into the investment planning process. You don’t want to be forced to sell your stocks during a nasty bear market for spending purposes, so at some point even investors with the highest tolerance for risk realize they need to keep a chunk of their spending needs in cash or bonds.

The depths of a bear market is not a great time to have this investment epiphany but a huge run-up in stocks is never a bad time to reassess your diversification profile.

When you’ve been proven wrong about an investment thesis. This one is more relevant for those who hold more concentrated positions in single stocks or niche ETFs. Every investor should perform a premortem that signals when it’s time to pull the plug and bail on an investment idea that simply didn’t pan out.

This can be harder than it seems because What if I just wait until it breaks even?! or What if it rallies right after I sell?! are both rather compelling arguments in a loser position.

When you’ve won the game. If you’re lucky enough to amass something in the neighborhood of 20-25x your expected living expenses in retirement and have a decent handle on your spending habits, at a certain point you may ask yourself — What’s the point of playing anymore?

This decision was much easier to make in a world that actually gave investors some form of default-free yield. Unfortunately, there is no more going to the beach and living off the interest anymore from high-quality bonds.

But if you built up a big enough nest egg and are secure enough in your lifestyle inflation, some may find it hard to continue taking so much stock market risk in their portfolio.

As long as you’re willing to sit out potential future gains to avoid bone-crushing volatility, I have no problem with this strategy.

When you’ve determined your risk profile, time horizon or circumstances have changed. Most investors assume portfolio moves should be dictated exclusively by what’s going on in the markets.

Let’s look at the CAPE ratio, interest rates, Tobin’s Q formula, advance-decline line, bull-bear sentiment readings, 1, 3, 5, and 10-year performance numbers and so on.

And sure, understanding the past and present about the markets can help make informed decisions about the future.

But every portfolio decision doesn’t have to come down to market fundamentals.

You also must consider how your current circumstances impact your risk profile. Sometimes you need to dial down the risk because you’re in a better place financially than you expected. Maybe you received an unexpected windfall or don’t spend as much as you budgeted for.

It’s impossible to create a portfolio if you don’t have a handle on your goals and a reason to invest in the first place.

Markets matter but you should always begin the decision-making process by thinking about where you are and where you’d like to be.

UPDATE: A few days after the story about the Fidelity data ran in the WSJ they issued the following correction:

Of the 7.4% of investors ages 65 and up who made a change to their portfolio between February and May, nearly a third moved some money out of stocks, according to Fidelity Investments. Also, of the 6.9% of investors across all age groups who made a change to their portfolio between February and May, 18% moved some money out of stocks. An earlier version of this article, and a chart that was published with it, incorrectly said that nearly a third of investors ages 65 and up and 18% of all investors sold all of their stockholdings some time between February and May. (Corrected on June 18, 2020)

So the numbers and chart I used in here were WAY off. Not nearly as many investors dumped their stocks as originally reported. Regardless, the ideas here about when to sell still apply as far as I’m concerned.