As of 1991, a social worker named Shirley Sauerwein had never purchased a single share of stock in her life. “I didn’t understand it,” she told the Wall Street Journal in December of 1999.

Then she heard about a local company on the radio:

Then, while driving one day, she heard on the radio that a local company “had signed a contract with Russia that sounded interesting.” After calling for more information, she set up her first brokerage account and bought 100 shares at $12 each. Today, that company is MCI WorldCom Inc. Her original $1,200 now is worth $16,000, part of a mid-six-figure portfolio that includes Red Hat Inc., Yahoo! Inc., General Electric Co. and America Online Inc.

“I’ve doubled my money in two years,” says Ms. Sauerwein, who is 55 years old. “I’m staggered, aren’t you? It’s amazing. You can’t make that in social work.”

She eventually cut back on social work to become a full-time trader during the week with a stated goal of making $150,000 a year in annual trading profits to retire on.

This piece was written a few short months before the market peaked, sending the S&P 500 down by more than 50% and the tech-heavy Nasdaq down a gut-wrenching 80%. I wonder how her full-time trading career turned out.

These types of stories were commonplace at the time.

In her book Bull: A History of the Boom and Bust, 1982-2004, Maggie Mahar notes, “In 2002, fully 56 percent of those who owned stocks or stock funds had purchased their first shares sometime after 1990, while 30 percent of all equity investors had gotten their feet wet only after 1995.”

Noobwhales of all shapes and sizes were lured into the stock market by the promise of easy money and overnight riches. More than 100 IPOs in 1999 saw first-day pop of 100% or more. Over the course of the 1990s more than 250 stocks rose more than 1000%.

The dot-com bubble made the stock market too tempting to pass up for aspiring day traders. This type of behavior makes sense during a mania.

But what about during a depression?

This is one of the strangest economic crises in history. Stocks continue to surge higher in the face of the worst economic data of our lifetime. Housing demand has already surpassed pre-crisis levels. And even though the first quarter was the most volatile period since the Great Depression, people opened new brokerage accounts at a record pace.

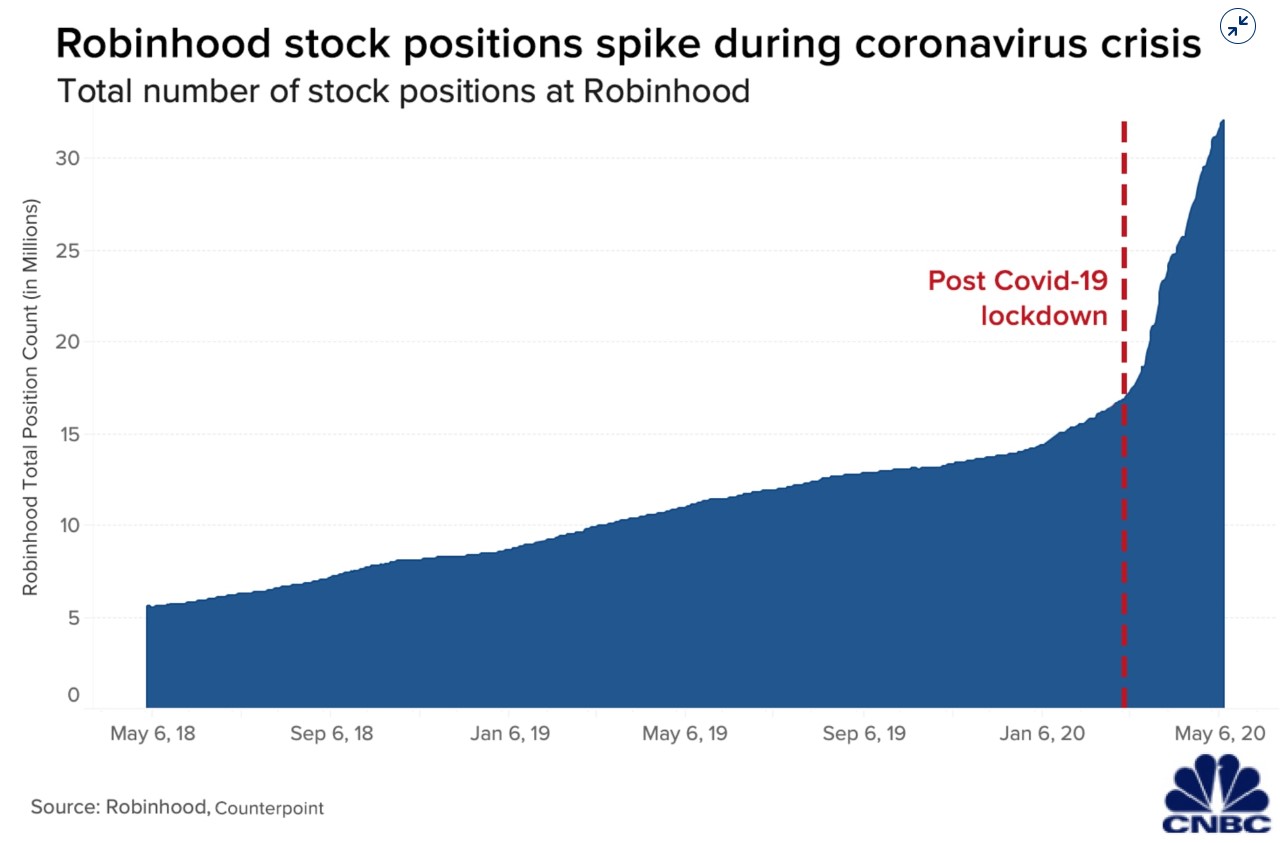

Despite their entire trading platform failing to function during some of the wildest days during the sell-off, smartphone trading app Robinhood was just able to raise additional capital on the back of 3 million new customers already this year. Robinhood estimates more than half of new accounts came from first-time investors.

According to CNBC, the major brokerages — Robinhood, Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade and Etrade — saw new accounts grow as much as 170% during the first quarter.

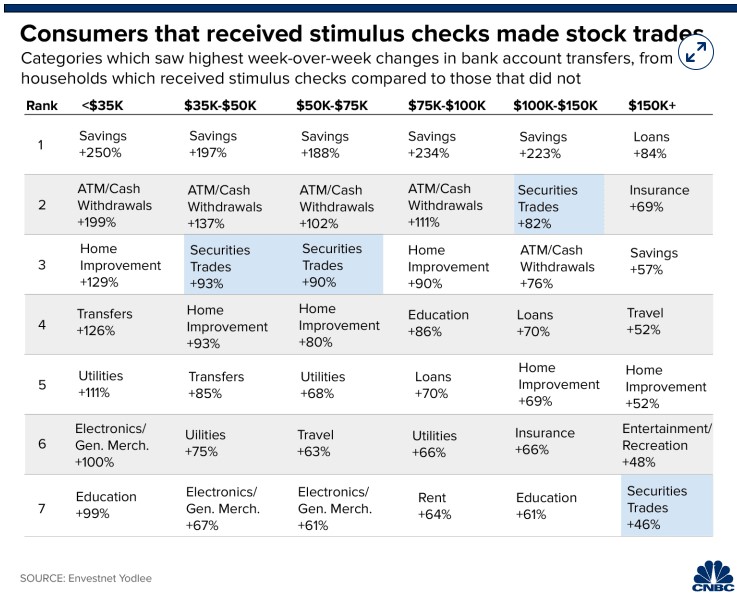

Data aggregator Envestnet Yodlee tracks the spending categories that saw the biggest week-over-week changes following the stimulus checks mailed out by the government. One of the biggest beneficiaries was securities trading:

This is not exactly textbook panic behavior. When the economy and markets are getting crushed that’s typically when retail investors say goodbye to the market and vow to never return.

So what’s going on here? Why are we seeing bubble-like behavior by the crowd during a time when they’re usually running for the exits?

Some theories:

Free trading. The great fee war of the 2010s ended in October when Charles Schwab, Etrade and TD Ameritrade all decided to come down to Robinhood’s level by eradicating trading fees. Fees were already dirt cheap to begin with but there’s something about the prospect of free that gets people excited.

Just think about how much more people drink at weddings with an open bar or all of the vultures that constantly circle the free sample stands at Costco. You almost feel like an outlaw when you get something for free that you usually pay for.

This might be a case of right place, right time for a massive upswing in trading.

Everyone wants their own generational buying opportunity. Investors have been beaten over the head for the past 12 years about what a wonderful buying opportunity stocks were in 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011 and so on.

Literally every single time the U.S. stock market has fallen in its history, it has eventually come back to surpass previous highs. Eventually, some investors and speculators were bound to learn that buying during a panic is the right move.

Here’s the headline from one CNBC story:

Every market correction isn’t going to be a generational bottom but investors may have learned it’s better to get in when things look awful.

People are bored. Degenerate gamblers have nothing better to do with their time. Casinos are closed. There are no sports to bet on. There is nothing else to do for most people while they’ve been stuck at home.

And gambling on the stock market flew into the stratosphere as the crisis erupted:

The stock market is a form of entertainment for many people right now.

Jay Yarow shared that CNBC’s website had over a billion page views in March:

As my wise friend Phil Pearlman likes to say, “The higher the VIX the higher the clicks.”

People pay more attention to their finances and the stock market when everything goes to sh*t. That’s just human nature.

Maybe this behavior changes as things begin to normalize somewhat (assuming there is such a thing as normal right now). People could abandon these accounts if they lose some money or find something else to bet on.

Or maybe people decide they enjoy betting on the stock market.

Who knows?

We like to think human behavior is easy to predict but the environment has a huge impact on our collective behavior.

And the current environment is one of the weirdest we’ve ever seen.

On this week’s podcast, Michael and I discussed the potential of a bubble if we get a vaccine and possible behavioral changes based on what happens in the months ahead:

Further Reading:

Making Sense of a Stock Market That Doesn’t Make Any Sense