In finance 101 they teach you an asset is worth the present value of future cash flows discounted at a reasonable rate of interest.

Let’s assume you have a business that produces $1 of earnings that will grow at 5% per year for the next 30 years.

If we were to discount those 30 years of cash flows at the same rate as the growth in earnings (5%), that would give us a present value of $28.57.

Since we’re making assumptions here, let’s pretend markets are relatively efficient so they value this company’s stock at exactly that present value.

But what if there is a depression and earnings drop from $1 to $0 in year one, increasing back to $1 and the 5% growth rate thereafter? In this case the present value of those future cash flows drops to $26.30, a decrease of 8%.

What if earnings really tank and stay at $0 for another year before reaching $1 in the third year and then get back on the same growth trajectory? Now our present value is $24.19, a decline of 15% from the original valuation.

Or maybe the depression lowers earnings for a number of years? So let’s take year one earnings down to $0 from our original $1 estimate and assume in year two that earnings resume at $0.75. At a 5% growth rate, those cash flows wouldn’t reach their original $1 level for another 6 years.

In this scenario, the present value now goes down to $19.73 or 25% lower than the original price.

This is a novel example of discounted cash flows and there are probably a hundred other variations and discounting mechanisms I could have used here to make this more realistic but you get the point.

The earnings numbers for the stock market over the coming quarters or even years could look something like this example. We could see some insanely low earnings numbers for the stock market as a whole. Is it possible they even go negative for a quarter or two? Nothing is off the table at this point.

Investors who get caught up in a short-term mindset may assume if earnings crash 90% or some massive whatever the number is, that stocks should crash by a similar amount.

This line of thinking is short-sighted because it ignores the fact that the stock market is discounting not just this year or next year’s earnings numbers and cash flows, but cash flows many, many years out into the future.

I’m not suggesting the stock market is intelligent enough to know what earnings will be many decades out into the future.

But my simple example shows why a catastrophe in earnings doesn’t have to translate into the same catastrophe in the stock market.

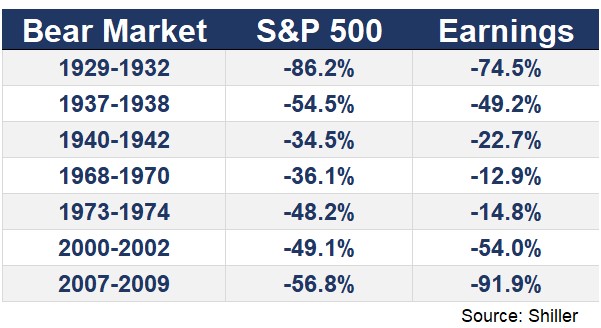

The worst market crashes tend to see a huge drop in earnings but the relationship isn’t perfect:

You can throw out the 1970s examples because that’s a time when inflation actually existed. The other four times when stocks were cut in half or worse saw earnings fall a lot but the declines didn’t always match up.

Stocks did worse than earnings during the Great Depression while earnings fell much further than stocks in the Great Financial Crisis.1

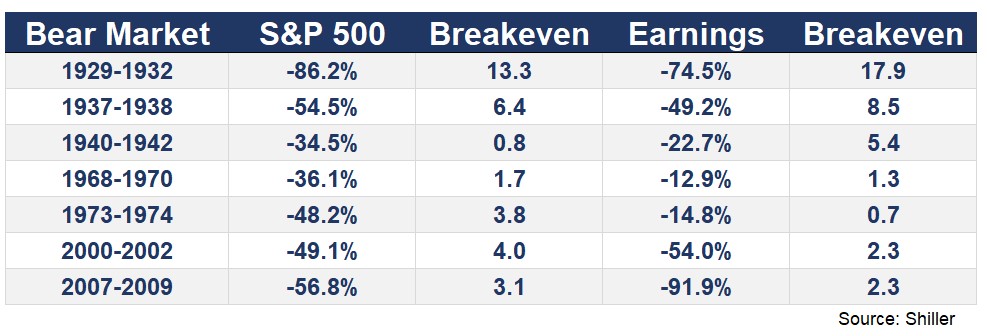

It’s also instructive to compare the breakeven periods (in years) for stocks and earnings:

Surprisingly, earnings took even longer than the stock market to rebound following the Great Depression. They were underwater for nearly 20 years! Over the last two crashes earnings actually rebounded much quicker than stocks which likely provided a tailwind for the bull markets that followed in both instances.

There are a few caveats anytime you try to use financial theory to explain what could happen in the markets. It’s true that the price of an asset should reflect the present value of all future cash flows but investors often over- or under-react based on their expectations of the future, meaning the pendulum can swing far above and below fundamental values.

While terrible earnings numbers will certainly have an impact on the stock market, how investors react to those numbers and how that impacts their expectations about the future will have a lot to say about how bad things get in the market. In the short-term investor reactions to the news matters more than the news itself.

This example probably doesn’t fly for individual companies as much as the overall market either. A company with no earnings for a long stretch of time could cease to be a going concern and go out of business while that doesn’t really happen to the overall market.

Earnings numbers for the first quarter should start trickling in over the coming weeks. They won’t be pretty and will look even worse in the 2nd quarter.

How much that matters to stock prices will be impacted more by how investors react to these numbers than the true fundamentals themselves.

Investors are now wondering what kind of multiple should be placed on a market where there potentially are no earnings. In a follow-up piece I will look at why valuations don’t matter in a bear market as much as people think.

*******

Credit where credit is due — the idea on this one goes to Bill Bernstein who mentioned it in our chat earlier this week:

Here’s the rest of our talk if you missed it:

Words of Wisdom from William Bernstein

1It’s worth mentioning one of the reasons 2007-2009 earnings fell so much had a lot to do with the enormous write-offs in the financial sector.