One of the biggest misconceptions about the Fed’s monetary policy is that low interest rates immediately cause investors to speculate or take on more debt. It would be silly to argue there hasn’t been any yield-chasing or excess risk-taking in recent years but there is a big difference between interest rate levels and credit (or the demand for loans).

Econ 101 teaches us that lower interest rates should cause an increase in the demand for capital, leading people to spend more, thus increasing inflation as the economy grows. That hasn’t happened and money has been easy for going on 10 years now. That’s because econ 101 doesn’t take into account the human element.

Here’s a piece I wrote for Fortune explaining why this is the case.

*******

WeWork is one of the biggest success stories of this decade. Founded in 2010, the company is now valued at just under $50 billion. The company’s valuation is eye-popping for a number of reasons but one of the biggest head-scratchers is the fact that the company lost nearly $2 billion last year. WeWork is still in growth mode so investors are hopeful those losses will pay off in the future as they look to scale up to office buildings all across the country.

WeWork is not alone in building a new company from scratch that exhibits hyper-growth coupled with big-time losses. Uber went public earlier this year with a $70 billion valuation but stated in their public filing that the company “may not achieve profitability.” As in, one of the biggest risks to investors is Uber may never turn a profit. After WeWork’s first bond sale last year, they announced a new metric to look beyond these losses called “community-adjusted EBITDA” which subtracted just about every expense you could think of to make the results look better than they actually are.

Skeptics abound when new companies make these types of statements. Many assume the era of cheap money from the Fed’s easy monetary policy has given these companies a longer runway to continue their growth while piling up losses. There may be some truth to this idea if there is evidence the Fed has extended economic cycles through low interest rates. But it’s hard to argue venture capital investors are comparing their opportunity set of new and exciting private businesses to the short-term interest rates they could earn in boring old fixed income. The risk profiles of these asset classes aren’t in the same ballpark.

Blaming the Fed for “blowing bubbles” (essentially pushing investors to take risks by keeping interest rates so low) misses the fact that investor preference and human nature inevitably overwhelm the level of interest rates. For example, the late-1990s dot-com bubble saw investors collectively lose their minds over tech stocks.

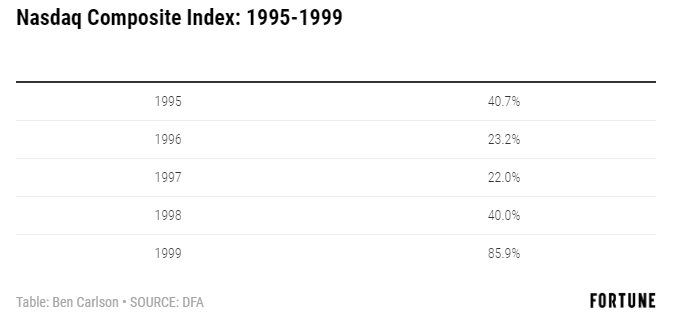

The Nasdaq Composite Index was up nearly 200% from 1995-1998. Then in 1999, it ran up another 85%, good enough for a 5-year total return of 450%. During this 5-year stretch, the 10-year treasury yield averaged just over 6%. That’s triple the current 2% yield on the 10-year so higher interest rates didn’t snuff out risk taking in that bubble.

Then there’s Japan, a country who has seen interest rates on the floor for going on three decades. The Bank of Japan has effectively capped their 10-year government bond yield at 0%, yet there hasn’t been a hint of a bubble in its financial markets since the late-1980s. Low interest rates alone are not enough to spur speculation.

During the real estate bubble of the early-to-mid 2000s, mortgage rates were much higher than they are today. The Case-Shiller Home Price Index rose almost 70% from 2001 to 2006 while 30-year fixed-rate mortgages averaged 6.2%. Over the past 5 years, the Case-Shiller Index is up nearly 27% while mortgage rates have averaged just 4%. Human nature matters more than interest rates when determining how far investors are willing to take asset prices.

As John Maynard Keynes once wrote, “Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits—of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.” Said another way, emotions matter much more than spreadsheets when humans are making decisions with their money.

So until they become a more seasoned enterprise, a company like WeWork is at the fate of Keynes’s animal spirits, not central bank policy. And increasingly, in the private markets, those animal spirits are derived from institutional investors. In the past, institutions such as pensions, endowments, and foundations invested conservatively in publicly-traded stocks and bonds. Now many of these portfolios are filled with private market investments.

According to the NACUBO-TIAA Study of Endowments, those colleges with $1 billion or more in endowment assets now have nearly 60% of their assets in alternative strategies, which includes things like private equity, venture capital, and hedge funds. That’s a far cry from your grandfather’s 60/40 stock/bond portfolio.

Today’s institutional investors are also in competition with sovereign wealth funds and WeWork’s largest investor, Softbank, which sports the world’s largest technology fund, the $100 billion Vision Fund. Venture Capital firms themselves are growing rapidly as well. Marc Andreesen and Ben Horowitz recently raised nearly $3 billion in two new funds for their firm a16z. The firm opened its doors in 2009 and already manages upwards of $10 billion.

The institutionalization of the private markets has allowed a company like WeWork to stay private for much longer than companies would have dreamed of in the past. This influx of cash even allowed co-founder Adam Neumann to cash out more than $700 million from his stake in the company through a combination of stock sales and debt according to the Wall Street Journal.

Public markets will soon have their say about WeWork. But for now, a combination of investor preference for hypergrowth companies and a willingness of institutional investors to front them capital are fueling its rise.

This piece was originally published at Fortune. Re-posted here with permission.