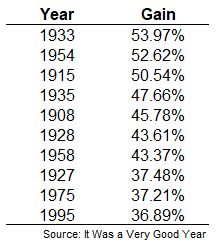

These are the 10 best years in stock market history (for the Dow) going back to the year 1900:

This list came from the book It Was a Very Good Year by Martin Fridson, which uses these high-flying years in the stock market to provide a historical look at what was going on leading up to and during those periods.

Fridson’s book was published in the late-1990s. Since then the Dow has seen gains of 28.0% (2003), 22.5% (2009), 29.4% (2013) and 28.0% (2017) but nothing good enough to crack the top 10.

This was one of those books that made me wonder ‘Why didn’t I think of that?’ because it’s a wonderful way to look back at the markets and economy through a unique historical lens.

Here are some lessons:

The stock market is counterintuitive. The 1915 gain of more than 50% might be the most impressive on the list since it came during World War I. Those gains also occurred after trading was suspended in the stock market in 1914 which was the first time it had been done since 1873. The market was closed from the end of July to mid-December of 1914.

Then 1915 happened.

The way we look at stocks has changed over time. I’ve written previously about the fact that comparing bond yields and dividend yields was a workable signal until the 1950s when it stopped working.

One of the reasons people paid such close attention to this relationship is because dividends used to be the only thing equity investors paid attention to.

Fridson writes about the thinking behind this relationship in 1915:

Journalists commonly equated the established dividend payout with the return on the stock, giving little thought to possible appreciation. They compared the payout rate directly with prevailing bond yields; total return’s day hadn’t yet arrived.

It’s important to remember how market dynamics can change over time when looking back at historical data.

Volatility clusters but it works in both directions. The biggest gains in the stock market are typically seen around the biggest losses.

The nearly-50% gain in 1935 was the fourth time in nine year stocks had advanced 35% or more (see also 1927, 1928, and 1933). Shockingly that 9 year period, which includes the nearly 85% crash in stocks during the Great Depression, would have led to a total return of almost 60%!1

Of course, stocks would fall 50% a couple of years later in 1937 but it’s wild to think how big some of those gains were sandwiched around the enormous losses of the 1929-1932 debacle.

Stocks were actually relatively cheap before the blow-off top before the Great Depression. In 1926, the P/E ratio on the Dow (which included just 20 names at that point) was just 11.7x. Then investors went nuts and the market doubled in 1927-1928.

Even the best investors can get crushed. Benjamin Graham warned about how “speculators had gone crazy” after the late-1920s melt-up. Even with those warnings and a “defensive” portfolio, Graham would lose 20% in 1929 and another 51% in 1930. Like most others at the time, Graham had to cut back on his lifestyle to make it through the depression.

Inflation in the 1970s was brutal on the stock market. The gains in 1975 started from one of the lower valuation entry points in history. The price-to-earnings ratio on the Dow bottomed out at 6.2x in late-1974, even lower than valuations seem during the depths of the Great Depression. Stocks were also yielding a monstrous 6.2% at the time.

Market timing requires being right twice. William Durant deftly sold out of the market in May 1929, giving him plenty of time to avoid the vicious crash which began in October 1929. But he jumped back in and bought on margin shortly thereafter to pick up some bargains, all of which only went on sale much further.

By the end of the year, as stocks continued to crater, he started getting margin calls. By 1930, he was wiped out. When he couldn’t meet a $5 million margin call, he said, “I’m the richest man in America…in friends.”

Regulations were few and far between back in the day. Fridson tells the story of Joe Kennedy, father of JFK and RFK, and his penchant for insider trading when he began his career on Wall Street.

In the early-1900s trading on material non-public information was considered unsavory but not yet illegal. Kennedy told a Harvard classmate when he was a young investor, “It’s so easy to make money in the market, we’d better get in before they pass a law against it,” after turning $24,000 into $675,000 from advance knowledge of the acquisition of a coal company.

Stocks are not the economy but they used to be (for the most part). Fortune Magazine wrote in the 1950s:

The market is no longer a very reliable barometer of business prospects, or even a reliable barometer of business conditions. Before World War II, what happened to stock prices and the volume of transactions was a reasonably good omen of future business trends; turns in stock prices anticipated turns in business 80 percent of the time before 1939. Since then, however, the market has been a voice in the wilderness of lower Manhattan, unheeded and often off key.

Maybe people at the time just thought the stock market tracked the economy but this is just another reminder that things are far from static when it comes to predicting what’s going to happen when it comes to markets or the economy.

Wall Street looked very different. Wall Street is big business these days but for decades following the Great Depression is was a shell of its former self.

Brokerage firms were forced to shut down in the 1950s because they were losing money. According to Barron’s at the time: “Amidst the greatest prosperity in U.S. history, Wall Street has become a depressed industry.”

Fewer shares were traded in 1953 than 1925, and there were six times as many companies listed in the 1950s. Seats on the exchange sold for the same prices they had all the way back in 1899.

Source:

It Was a Very Good Year

1Once again, start and end points matter when looking at performance numbers.