In his book The Ages of the Investor, William Bernstein describes a mythical employer named Uncle Fred who offers investors a retirement savings scheme determined by the flip of the coin. One side of the coin results in a +30% annual gain while the other side gives you a -10% loss in a given year.

Since the coin toss gives you a 50/50 shot at each outcome, this would give investors a compounded annual return stream of around 8.2% with a 20% standard deviation, not too far from the actual long-term results in the stock market.

Now let’s say you decide to contribute $1,000 each year for the next 40 years into Uncle Fred’s scheme. And let’s further assume the coin flip works out to give you 20 positive return years in a row followed by 20 negative return years in a row. In this scenario, you would end up with a little more than $100,000. Not bad, but you barely kept up with the long-term inflation numbers.

We can also look at the opposite side of this coin — 20 consecutive years of negative returns followed by 20 consecutive years of positive returns. This time your nest egg grows to more than $2.3 million!

These scenarios include both awful and amazing luck, but this shows how the sequence of returns can lead to enormously different outcomes, even with the same annual returns from the market.

Sequence of return risk exists not only in the financial markets but also everyone’s own personal finances. When you were born can have an outsized impact on where certain generations stand financially.

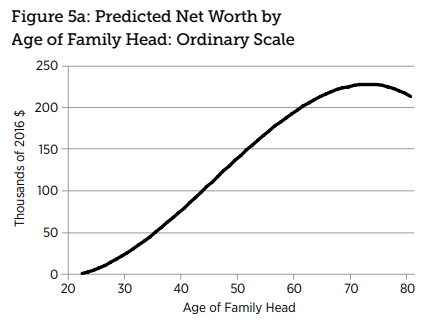

Researchers from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis put out a report called the Demographics of Wealth which looks at how financial outcomes are often shaped by when we were born. They posit there’s a pronounced life cycle of wealth that looks something like this:

They further explain:

The typical family’s wealth traces out an upward sloping arc over most of its life cycle, beginning around zero in the early 20s and reaching a peak of about $228,000 at age 72. The range of actual wealth accumulation across families is very large, but the typical family’s experience is well-described as rapid initial growth in percentage terms followed by steady deceleration and eventual decline—albeit slight—throughout the rest of the life cycle. The shape of the wealth life cycle is influenced by economic and financial developments over time.

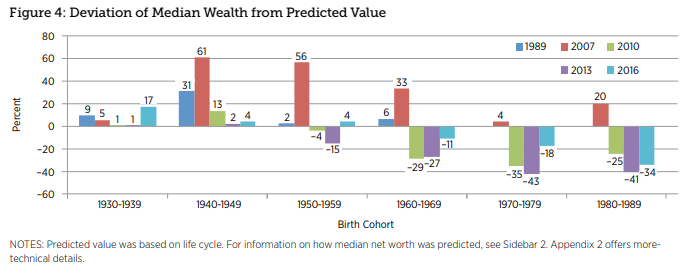

If only it were that simple. In their report, the Fed looked at three different generations to determine how their wealth has been impacted by the year in which they were born.

They looked at people born in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s to see where each group falls on their predicted wealth scale. Those born in the 1960s have an 11% shortfall while the 1970s group is 18% behind where they “should” be. But by far the group that is furthest behind is those born in the 1980s. Millennials are 34% below their predicted wealth levels based on the experience of earlier generations at the same age.

You can see how these numbers have changed over time here:

The recession decimated a lot of wealth and much of it hasn’t come back for many people. And young people have likely experienced a double whammy from the fact that many missed out on the huge gains in the financial markets over the past 10 years or so.

There are some reasons to remain optimistic about the finances of young people.

The group born in the 1980s is by far the most well-educated of the three and thus has the potential to be the highest-earning group ever. Those earnings may just be a little delayed as young people pay for that education.

This late start is not ideal but young people still have oodles of time in front of them, especially when you consider our lifespans are increasing over time.

People born in the 1960s and 1970s may have more financial assets but millennials have the greatest asset of all — human capital. The combination of higher-earnings potential and more time in front of them mean all is not lost.

While it would have been great for young people to pick up financial assets on the cheap during the Great Recession, my fellow 1980s babies can still make up for their shortfall. We just have to take advantage of our human capital by juicing our savings when those potential earnings become a reality.

The best way to decrease the risk of the sequence of your returns is to frontload your purchases in stocks at an early age. Early typically means your 20s but even those in their 30s and 40s may still have 6 to 7 decades ahead of them to allow compounding to do the heavy lifting for them when you include the retirement years.

Bernstein writes:

What we have learned here is that investing all of your money up front in stocks avoids “sequence risk.” That is, with a lump sum, a particularly good or bad sequence of returns will not affect your final result one bit. Of course, unless you began your adult life as a wealthy heir, you don’t have that option. But the corollary still holds. Investing as much as possible in stocks and other risky assets up front maximally mitigates sequence risk.

To wit, it’s virtually impossible for young workers to deploy their investment capital too aggressively, because their human capital overwhelms it.

Sequence of return risk in the markets is completely out of your control. So is the year in which you were born, which is why luck often plays a larger role in people’s financial outcomes than most are willing to admit.

But you do control your savings rate and how much money you spend on discretionary items. Even though young people may be behind financially because more of us went to college than the older generations, there is still plenty of time to make up for that shortfall.

You just have to start sooner rather than later.

Further Reading:

Millennials and the Death of Equities