Home ownership is often called both the American Dream and the biggest investment of your life.

It’s debatable whether a house is truly an investment or not, especially when we’re talking about your primary residence.

Whether it’s an investment or not, house prices do change over time and the equity you build can be impacted by those price movements. So it makes sense to understand what the potential price moves could be over the long haul.

A group of researchers from the San Francisco Fed put out a piece this month that sought to do just that. Oscar Jorda, Moritz Schularick and Alan Taylor recently released The Total Risk Premium Puzzle to compare the long-term returns in residential real estate to the other asset classes.

They found from 1870-2015, worldwide housing returns were 6.9% after inflation, versus 6.7% for the stock market. Those were global numbers. In the U.S., stocks beat real estate 8.5% to 6.1% in real terms. And they also showed the volatility of real estate prices were lower than stock market returns.

I give these gentlemen credit for their work in this endeavor but I have a few qualms with the data here.

First of all, there’s no way you can definitively say real estate has experienced lower volatility than the stock market for the simple fact that stocks are liquid and houses are illiquid. That would be like saying the steep drops and corkscrews on a roller coaster didn’t really happen because you rode it Sandra Bullock-style with a blindfold on.

There are benefits to the fact that there’s not a tradable market for your home 5 days a week for 6-and-a-half-hours a day. The price fluctuations would drive people insane, especially when you consider the dollar amounts involved. But just because you can’t see the price changes doesn’t mean your asset is any less volatile. Your house is just part of Schroedinger’s portfolio.

Any data going back to the 1800s is suspect, whether it’s used for the stock market, housing, or avocado toast menu prices. There’s just no way the records going back that far are reliable.

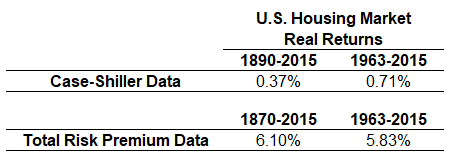

The Case-Shiller Index has been the most widely used pricing data for long-term real housing returns up to this point. In comparing the two data sets, there’s a stark contrast between the real returns in each instance:

Someone much wonkier than me could go through each data set with a fine-tooth comb to figure out the exact differences in methodology but my guess is both data sets are wrong in their own way.

The authors of the study were also comparing the entire global data set of homes in existence. To suggest their data should lead you to conclude that owning your own home is as good of a bet as investing in the overall stock market would be like looking at the overarching history of stock market returns only to conclude that buying a single company could give you a similar outcome.

In no way does owning one, two, or even ten homes give you broad enough diversification in residential real estate to make an apt comparison to the overall market.

Comparing real estate to the stock market or bonds or any traditional asset class is difficult because there are so many other variables involved in real estate.

There are taxes and costs involved just like there are in the stock market, but then you have to consider the leverage involved, the cost of borrowing, the length of time in the home, the imputed rent, the psychic income from home ownership and the fact that you have to live somewhere.

Unless you’re buying houses for the rental income, you have to either buy or rent a place to live. That means housing is a form of consumption. Investment, on the other hand, is a form of delayed consumption.

I can understand comparing publicly-traded REITs to the stock market because it’s much more of an apples-to-apples comparison. I would even accept a comparison to rental properties or commercial real estate investments.

But comparing your home as an investment to the stock market makes little sense.

Some people saw this new study as proof more Americans should be investing in real estate. As with most things, extreme positions in any one investment or asset class tend to increase your risk.

Risk can be exponentially higher in housing for the simple fact that it’s also the roof over your head. If something goes wrong with an investment in the market, you’re out some money and live to fight another day. If something goes wrong with an investment in your house, you’re out on the street.

I’m not saying people shouldn’t invest in real estate. There are plenty of professionals who know what they’re doing in the space. But before you head down that path, no matter what the historical return numbers show, first understand the risks involved in trying to make the roof over your head the biggest part of your nest egg.

Your home should certainly play a role in your financial plan but it shouldn’t be the entire plan.

Further Reading:

The Real Estate Market in Charts