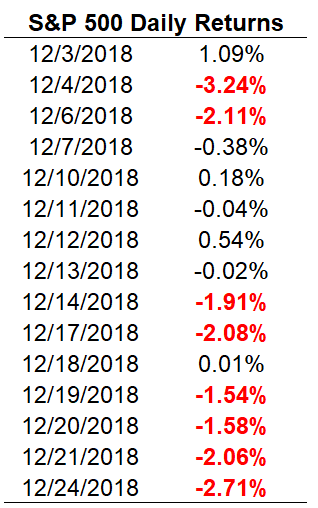

December was a brutal month for the stock market. Here are the daily returns through Christmas Eve (losses of 1% or worse in red):

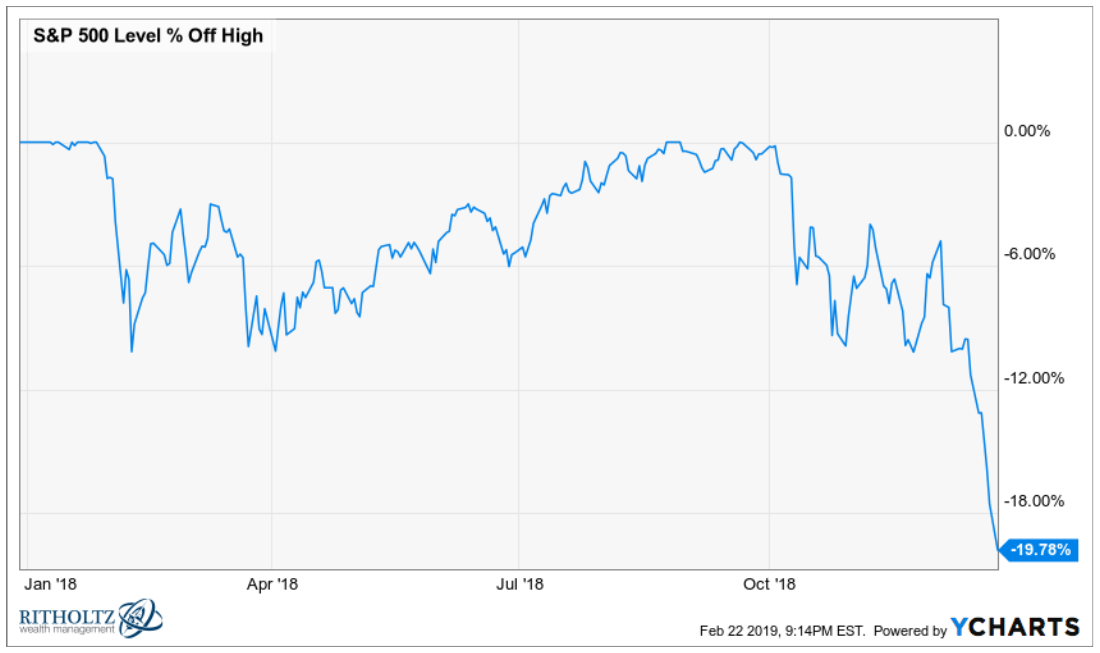

Not only was the S&P 500 down almost 15% for the month at this point, but it was in the midst of a bear market that began in late-September:

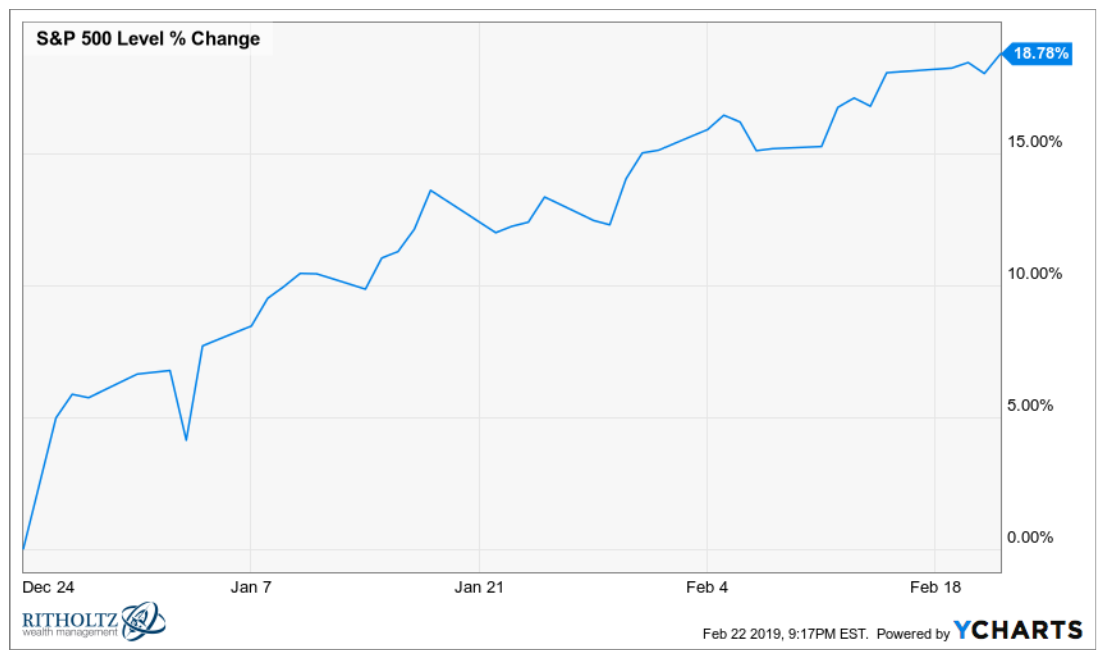

Then a funny thing happened the day after Christmas — stocks were up bigly. The S&P 500 rallied almost 5% in a single day.

A chorus of traders, prognosticators, investors, and market historians chimed in after that relief rally to decry, “Stocks don’t bottom on big up days.”

This is the kind of statement that makes sense when you study market history. Volatility tends to cluster in the markets because market fluctuations force people to overreact. That’s why the biggest down days tend to coincide with the biggest up days (see the data from Michael here).

The combination of big up days and big down days is one of the reasons bear markets are so difficult to navigate no matter how you’re positioned.

You know what happened next:

Stocks are up close to 20% since the Christmas Eve massacre. Stocks did bottom on a big up day, much to the chagrin of those who were so sure that could never happen.

And maybe in another timeline those people would have been right. It wouldn’t have been shocking to see volatility continue at that point because history shows it does happen in many instances.

This head-scratching market behavior is another reason to avoid overconfidence like the plague about what’s going to happen next in the markets.

Take always and never out of your vocabulary because markets love nothing more than to humble investors and traders who become too confident.

Things that have never happened before seem like they happen all the time now. And things that happened all the time before seem to follow a new script once investors assume they’ve got it all figured out.

No matter how confident you are in your strategy or market research you should always cherish your exceptions because markets are full of them. And if your strategy had no exceptions it would never work over the long-term because everyone would do it, thus taking away its ability to work.

Being a student of market history can be helpful in a number of ways:

- It can help you prepare for a wide range of outcomes.

- It can show you how human nature can take things to extremes.

- It allows you to think probabilistically about the future based on present circumstances.

- It aids in the expectation setting process.

- It proves almost everything in the markets is cyclical.

But studying market history does not:

- Help you peer into the future.

- Tell you exactly how investors will react under certain conditions.

- Show you how to avoid overconfidence.

- Take into account the fact that markets are constantly evolving.

- Teach you how to handle situations that have never happened before.

- Give you the map to future market returns.

My point here is not to stick it to all those people who missed this rally or got caught flat-footed when markets turned on a dime.

It’s certainly possible this is a huge head fake rally that rolls over sometime later this year. The S&P is still 5% or so below its all-time high in terms of the price index.

But this is a good case study in avoiding extremes, especially when it comes to short-term moves in the markets.

All-in or all-out. Always or never. Will happen or won’t happen.

Positioning yourself this way can make you feel like a hero but it also puts you in a position to compound your mistakes when you’re wrong.

And everyone involved in the markets is wrong from time to time.

Further Reading:

Big Up Days in the Stock Market