https://giphy.com/gifs/hello-austin-powers-introduction-QQkyLVLAbQRKU

A reader asks:

Does your Bond Bear Market note contradict your previous case for bonds? The conclusions are unclear to me.

I can see how this could be confusing. In a post last week I discussed the potential for bonds to do well if all the right pieces fall into place which was followed up this week with a piece showing an enormous risk in bonds historically.

So which one is it?

The truth is I don’t know but it’s likely bonds, interest rates, and inflation forge their own unique path from here. Historical scenario analysis can provide a rough outline of the past but it’s not a map of the future.

The reason I like to look at both positives and negatives for any segment of the market is it provides context for potential risk and reward. It helps me frame a range of outcomes, some of which may not come to pass.

Inflation is a tricky concept to pin down for investors. In terms of longevity risk, inflation can be a killer. But it’s much harder to feel in the moment, which is why portfolio construction and risk management require a balancing act in many respects.

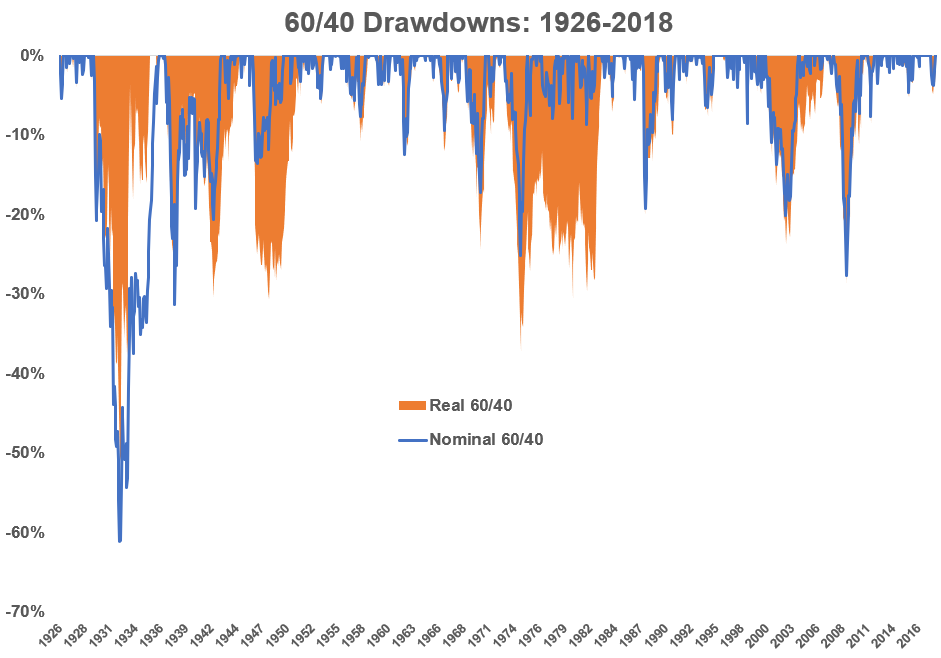

In my piece from earlier this week, I showed after inflation drawdowns for both stocks and bonds but didn’t look at them in terms of a balanced portfolio. The following shows a 60/40 portfolio consisting of the S&P 500 and 5-year treasuries going back to 1926 with both real and nominal drawdowns:

Inflation matters over time because it saps your purchasing power but during a sell-off investors don’t feel better or worse because of the latest CPI figures. Drawdowns were muted to some degree in the Great Depression because it was a deflationary spiral. Do you think that offered any solace to investors who were getting slaughtered in stocks at the time?

The 1970s and early 1980s saw much larger drawdowns on a real basis than they experienced nominally. I’m guessing inflation had a much larger impact on people’s personal finances — spending, income, etc. — and everyday lives than their portfolios.

More recently the differences between nominal and real haven’t been as pronounced.

You want to take inflation into account when you have multiple decades ahead of you to save and invest but you also have to be realistic about how you’ll make it through those decades.

Over the long history of these assets, let’s call it the last 100 years or so, stocks have returned roughly 5-6% above the rate of inflation while bonds have done 2-3% real. Stocks are a productive asset. Bonds are a loan that has to be paid back. Stocks are built for beating inflation over the long run. With bonds, it depends on the environment.

Does everyone need to own bonds?

Not necessarily. But plenty of investors overestimate their threshold for pain when the stock market has been going up every year since Avatar was the number one movie in the country.

Here are some reasons for owning bonds in a portfolio:

- High-quality bonds can provide an emotional hedge against reactive behavior due to stock market volatility.

- They can act as a shock absorber when the stock market crashes, and dry powder to rebalance into the pain.

- They can provide valuable diversification benefits which allow investors to earn stable income over time.

- For those with a large enough portfolio, why take excess risk when you don’t need to?

I’ve had a number of people tell me they’re fine owning a basket of dividend stocks. As long as you’re able to withstand the volatility that comes from a 100% stock market portfolio and understand dividends aren’t guaranteed, this can work.

You could have the safer side of your asset allocation in cash or cash-like products. Anyone in the shortest duration vehicles has seen their fixed income allocation hold up nicely as rates have risen over the past 27 months or so. But there is a cost to this strategy as well.

The short-term treasuries ETFs (BIL and SHY) are up 0.21% and 0.88% annualized, respectively over the past 10 years. The aggregate bond market (AGG) is up 4.01% per year in that time. So going short-term reduces your risk during a rising rate environment but that safety has a cost.

You could also own treasury-inflation protected securities (TIPS) to account for inflation. This is one of the few assets that explicitly protects your investments on a real basis.

The truth is there are a lot of strategies that can work but what really matters is being comfortable with the drawbacks of the strategy you choose because there’s no way to perfectly thread the needle.

One scary chart shouldn’t keep you from investing in an asset which has merit just like one beautiful chart shouldn’t nudge you into putting all of your money into a single asset.

My point in writing about these topics was to show there are no assets which exist without some form of risk. The reason I enjoy looking back at market history is that it reveals the many risks we face as investors.

Maybe the biggest risk for most people is assuming they know exactly what happens next.

I don’t attempt to predict the future but I do believe you can create probabilities based on the past to analyze the present. That means accepting that I don’t know what’s going to happen, but being informed sufficiently to build a diversified portfolio that’s durable enough to withstand a wide range of outcomes.

Further Reading:

The Worst Kind of Bear Market

The Case For Bonds

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- The ETF disease (Mullooly)

- That time an astronaut lost a wedding ring in space (Wired)

- The future of In-and-Out Burger (Forbes)

- Why big companies squander brilliant ideas (Tim Harford)

- Haste makes waste (Collaborative Fund)

- Peter Bernstein on the hidden variety in averages (Novel Investor)

- The allure of private (Belle Curve)