In Gary Shteyngart’s new novel Lake Success, the protagonist is a wealthy hedge fund manager named Barry who has a complete lack of self-awareness.

Shteyngart’s storytelling in this book is wonderful but when you read it the theme of wealth inequality slaps you in the face throughout.

At one point in the story, Barry and his wife are having dinner with a married couple in their building. To impress their neighbors, Barry pulls out a $23,000 bottle of Japanese whiskey called Karuizawa. He goes out of his way to ensure his dinner hosts know the price tag for effect.

After cracking open the bottle the subject of wealth comes up and Barry is on the receiving end of judgment from everyone at the table because of the obscene amount of money he makes in the hedge fund world:

“But do you know what to do with your money? We’re drinking two Hyundai Sonatas’ worth of whiskey tonight. But the only reason this whiskey has that price tag attached is that men like you can afford it.”

“And who does that hurt?” Barry said. “Who doesn’t win from this situation? The Japanese distillery? The whiskey merchant? You?”

“I just worry that the new signorial class distorts the picture for the rest of us. You create a world where anything but the utmost in wealth is seen as a moral failing.”

I was reminded of this exchange when I saw a story this week about a pair of sneakers for sale at Nordstrom:

You’ll notice the shoes are distressed to the point of looking like they should’ve been thrown away a long time ago. They retail for the bargain basement price of just…$1,645!? My only response to seeing this was: but why?

Fortune’s Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt by Arthur Vanderbilt tells a similar story of excess wealth during a different time. The Gilded Age of the late-19th century came about because of the Industrial Revolution. It saw a small group of families build massive amounts of wealth in a relatively short period of time.

Some stats from the book shed some light on this:

Before the Civil War, there were fewer than a dozen millionaires in the United States. In 1892, the New York Tribune published a list of 4,047 millionaires, over 100 of them having fortunes that exceeded $10 million. It was estimated that 9 percent of the nation’s families controlled 71 percent of the national wealth. As the self-indulgent old rich and new rich flaunted their wealth, paying on average $300,000 a year to maintain their city mansions and Newport cottages, $50,000 to keep their yachts afloat, and $12,000 each time they wanted to give a little party, hundreds of thousands of immigrants were jammed into tenements not far from the fabulous Millionaires’ Row. Thousands of child laborers worked in sweatshops for $161 a year. Common laborers made $2 to $3 a day, with the average worker earning $495 a year. Two-thirds of the nation’s families had incomes of less than $900; only one family in twenty had an income of more than $3,000.

In 1929, right before the crash, at the height of the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties, only 2 percent of all American families had had incomes of more than $10,000; 60 percent had had incomes of less than $2,000. In the Depression years, the disparity between the haves and the have-nots was magnified. As families slept in tar-paper shacks heated by fires in grease barrels, and fed their children a broth of dandelion greens, the rich worried about their incomes falling from $3 million to $800,000.

The craziest anecdote was a fancy party where cigarettes were wrapped in one hundred dollar bills. People were literally lighting their money on fire.

These numbers are even more insane when converted into today’s dollars ($300,000 would be the equivalent of $8 million today).

The disparity isn’t quite so wide today but when looking at the wealth statistics you get the sense that the difference between the haves and have-nots is creating our own mini-Gilded Age these days.

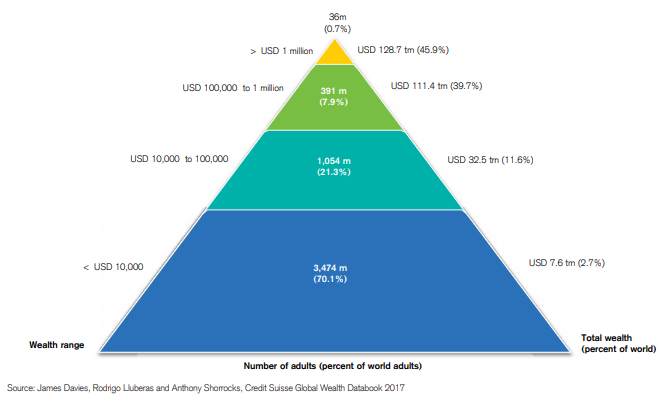

This wealth pyramid from the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report shows 36 million millionaires, less than 1% of the adult population, hold 46% of household wealth worldwide:

The good news is there is something like $280 trillion in wealth on the planet. The bad news is, that wealth is concentrated at the top of the pyramid.

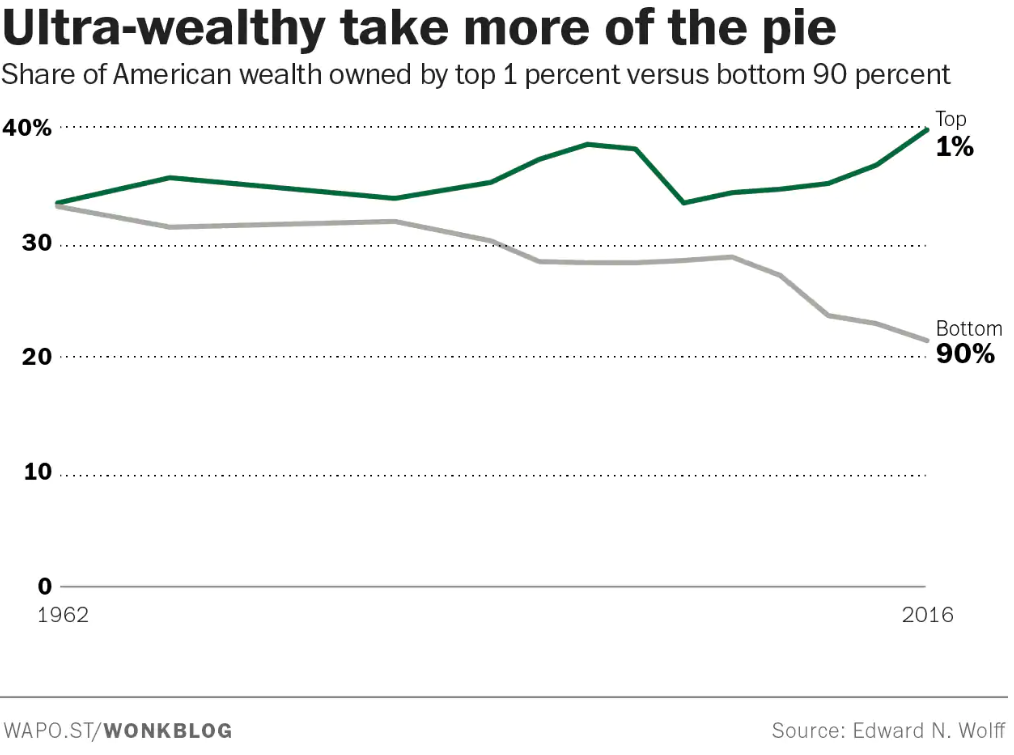

Things are even more concentrated in the U.S. as the top 1% now owns more wealth than the bottom 90% than at any time over the past 50 years:

A big reason for the growing inequality is the fact that the wealthy hold the majority of financial assets. The top 10% of American households own 84% of all stocks. And if you haven’t noticed, financial assets have been going up. If you missed the boat on the stock or real estate markets you’ve likely seen your wealth stagnate.

The one big difference between now and the late-19th/early 20th century is the fact that poverty has been improved by leaps and bounds.

The Wall Street Journal reported this week the global population living in extreme poverty has fallen below 750 million people for the first time since 1990, which is when the World Bank began collecting this data. That’s a decline of more than 1 billion people over the past 25 years. The wealth profile of the world is far from perfect but it is seeing improvements for the poorest in society.

If I had to place a bet on how things will look going out a few decades into the future I would expect to see a continuation of this trend. The wealthy will likely continue to get wealthier but the poor will see massive improvements in things like healthcare, education, and technology.

It took The Great Depression, two world wars, and much higher tax rates on the wealthy to eventually even things out a bit following the original Gilded Age.

But the biggest difference between these two time periods is the industrial revolution was really the spark that led to the growth of a middle class in this country while today it seems to be the middle class that’s being left behind.

Anything is possible but I don’t see this trend reversing anytime soon.

Further Reading:

Inequality in the Stock Market