After reading one of my pieces someone recently commented that my whole schtick is simply pointing out how hard it is to invest successfully. This was meant to be a put-down but in some ways it’s true.

I write a lot about how hard investing can be because it is hard. Anyone who tells you it’s easy is delusional or trying to sell you something. One of the biggest first steps you need to take as an investor on the road to success is admitting that it’s hard.

On an episode of The Curious Investor, AQR’s Gabe Feghali and Dan Villalon discussed one of the hardest aspects of investing — market timing.

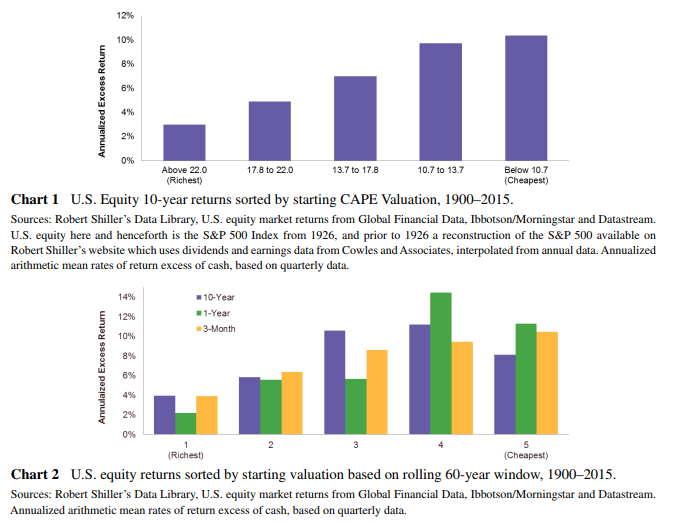

First, they looked at the firm’s research on valuations. Not surprisingly, AQR has found when valuations were high in the past, returns over the next 5-10 years tended to be lower. And when valuations were low, returns over the next 5-10 years tended to be higher.

This shows the excess return of stocks over cash historically by CAPE ratio:

But when they tried to translate this research into a market timing tool, the results proved disappointing for anyone looking for a silver bullet. This is Feghali and Villalon discussing the research with their colleague Antti Ilmanen:

People use data to justify market timing. But it’s hindsight bias, right? If you know ahead of time when the biggest peaks and troughs were through history, you can make any strategy look good.

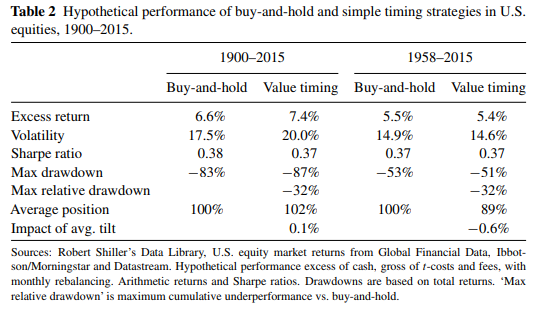

So Antti and his co-authors made a more realistic and testable market timing strategy. And here’s the key difference — instead of having all hundred years of history, Antti’s strategy used only the information that was available at the time. So, say for example it’s 1996, early tech bubble. We know after the fact that the U.S. stock market would get even more expensive for a few years before it crashed. But in 1996 you wouldn’t actually know that. So by doing their study this way, Antti could get a more realistic test of value-based market timing.

The interesting and troubling result was when we did this market timing analysis the bottom line was very disappointing. It was not just underwhelming, it basically showed in the last 50-60 years, in our lifetimes, you didn’t make any money using this information.

I looked up the paper referenced in the podcast and found the results:

The valuation timing model they used overweights stocks when they’re cheap and underweights them when expensive. You can see the timing tool hasn’t added value over the past 60 years or so and this is before accounting for fees or taxes triggered from sales.

I’m sure AQR (and everyone else for that matter) would love to figure out a way to time the market using valuation as an indicator. And I’m sure people can torture the data to find a strategy using valuation that would have worked perfectly in the past but you have to be realistic with your expectations about these things when thinking about the future.

AQR did find trend-following can add value since price tends to incorporate more of the short-term emotions in the markets than valuations but even that’s not perfect. You’re never going to be able to perfectly time market cycles in terms of adding or reducing risk in your portfolio. Even successful investing requires being uncomfortable and wrong much of the time.

Investors would love to find an easy way to tell them when to get out of the market to avoid an oncoming train on the tracks, especially at today’s elevated valuation levels.

Unfortunately, valuation is not going to do that for you because expensive markets can always get more expensive, fundamentals can change, and no one really knows what level of valuations will cause investors to change their perception of risk until after the fact.

Valuations are useful for setting expectations but not timing the market.

Source:

Market Timing: Sin a Little

Podcast:

Taking Stock of Stock Myths

Now here’s what I’ve been reading this week:

- Don’t drink the financial Gatorade (A Teachable Moment)

- Dear future me (Above the Market)

- Burning money is a dumb metaphor (Rad Reads)

- The curious case for emerging markets (Bps and Pieces)

- The invisible doctor, and rewarding incompetence (Dan Egan)

- The 4 laws of personal finance (Humble Dollar)