Marc Andreessen wrote one of the more prescient pieces of this century in the Summer of 2011 called Why Software is Eating the World. He laid out his reasoning behind the idea that technology is fundamentally changing the way we do business, likely for good:

My own theory is that we are in the middle of a dramatic and broad technological and economic shift in which software companies are poised to take over large swathes of the economy.

More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense. Many of the winners are Silicon Valley-style entrepreneurial technology companies that are invading and overturning established industry structures. Over the next 10 years, I expect many more industries to be disrupted by software, with new world-beating Silicon Valley companies doing the disruption in more cases than not.

He listed a number of reasons for his theory:

- Technology can be delivered around the globe at scale.

- Billions of people use the Internet and own smartphones.

- These tools make it easier than ever to launch new businesses without huge upfront costs.

This new business climate has caused many in the investment management world to call into question their strongly held beliefs about the efficacy of fundamental analysis when valuing businesses. I’m not sure what probability I would place on this being true but it’s quite possible this new world could completely change the way investors are forced to evaluate corporations and their financial statements.

This puts traditional value investing squarely in the crosshairs of the technological revolution, which has caused many within the asset management industry to rethink how they go about building portfolios.

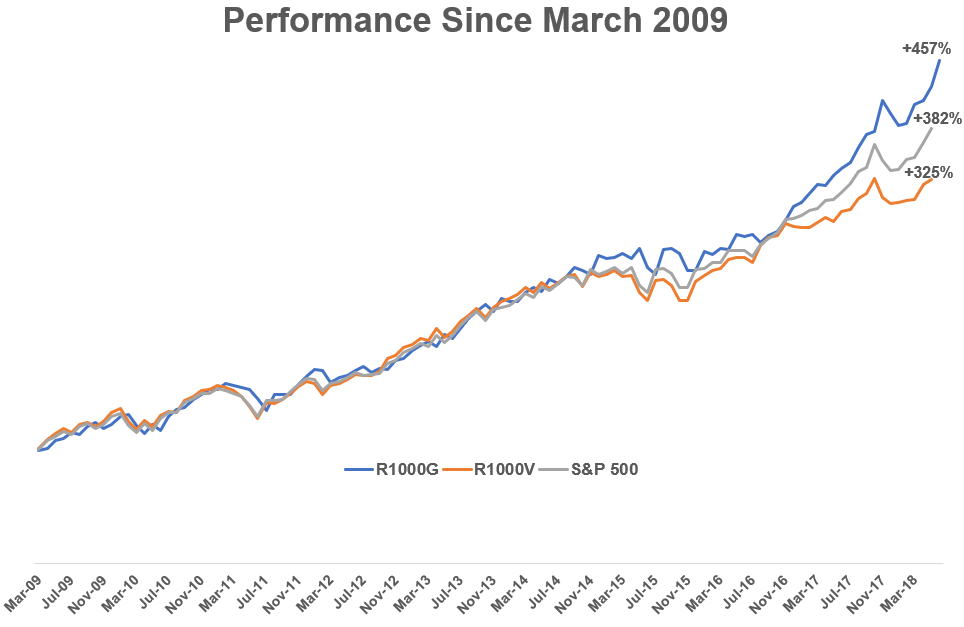

Its possible people are calling value investing into question simply because it’s underperformed growth investing by a wide margin for quite some time. This is the scorecard from March of 2009 using simple measures of value1 and growth:

It’s much easier to call for a paradigm shift when things are going poorly than when they’re going swimmingly. But it’s hard to argue things haven’t fundamentally changed in the make-up of corporations because of technological innovation. This is not your grandfather’s stock market.

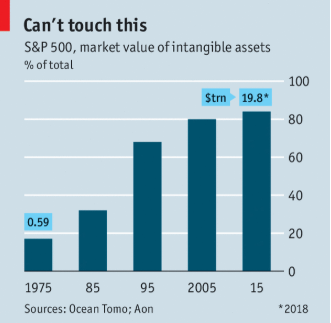

This chart courtesy of The Economist shows the enormous growth in intangible assets — things like patents, copyrights, franchises, goodwill, trademarks, etc. — since the 1970s in S&P 500 companies:

My friends at O’Shaughnessy Asset Management did a deep dive into how these balance sheet changes have impacted the stock market.

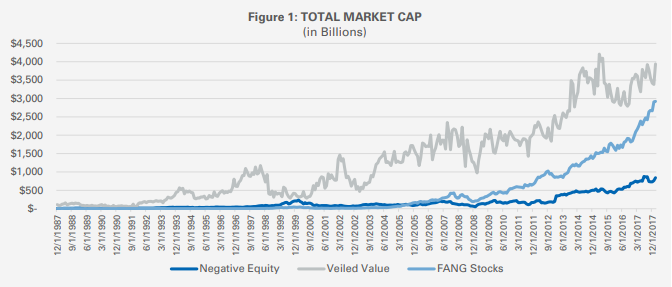

They broke the market into two groups:

(1) “Veiled value” stocks, which are companies that were in the most expensive third of all stocks ranked by price-to-book value but the cheapest third of all stocks by other valuation metrics (this group has grown from 60 companies worth $91 billion in 1988 to 258 companies worth $3.9 trillion today) and

(2) Companies with negative equity (which have grown from 13 companies worth $15 billion in 1988 to 118 companies worth $843 billion today)

This regime shift is relatively new as you can see from their chart in the growth of these groups:

The “veiled value” stocks are now worth more than the combined market cap of the FANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix & Google).

Add it all up and it feels like I’ve been reading lengthy quarterly letters from value investing shops for the past couple of years who have completely called into question the usefulness of utilizing the income statement and balance sheet as investors have done in the past.

I have a bunch of random thoughts on this topic, so here goes:

- It’s really hard to tell which one is worse — those fundamental investors who have stuck with their traditional investing metrics and gotten slaughtered or those who have completely abandoned their old way of valuing businesses to talk themselves into investing in Amazon and the like. Time will tell I suppose but right now I’m sure it feels much better to be in the latter group.

- Distinguishing the difference between discipline and flexibility within any investment strategy is one of the hardest things to do as an investor so I don’t really blame either group here. With the increased rollout of quantitative investment strategies at a low cost, I can see why many dyed-in-the-wool discretionary value investors have changed stripes in recent years. They almost had no choice in the matter to stay relevant while trying to hold onto assets. I’m just not sure how many of these asset managers have the ability to continually shift investment styles and understand the difference between cyclicality in the markets and paradigm shifts. Once you take that leap it becomes tempting to fall in love with style drift, which will eventually catch up with you. No one is good enough to pull that switch on a consistent basis.

- I don’t buy the idea that value investing is dead. If I had to guess, at some point over the next decade or so even the simplest forms of value will once again outperform, making everyone who gave up on them look like an idiot. That’s typically how these things work. Once they’ve been left for dead, investing strategies have a tendency for the meanest of reversions.

- My favorite value investing conspiracy theory, courtesy of Twitter, is that value stocks were overlooked in the past because it was so much easier to trade on insider information so people didn’t need to own value stocks. I don’t necessarily believe this but I love the effort in the concoction of the theory.

- FANG stocks and their ilk may have broken value investing for good but I still believe buying unpopular stocks will turn out to be a satisfactory investment approach over the long-term. How you define the horizon of that long-term will have a lot to do with your own definition of success in the matter, but I still think there’s room for a contrarian style of investing, even if it’s painful at times.

- It’s hard to say there’s a right or wrong way to approach the fundamental analysis of stocks. The “best” value factors are just the ones that have outperformed using the same historical data that every quant on earth uses to test their models. So there is something to be said for having the conviction to stick with whatever model you choose, as long as there is a reasonable rationale behind it.

- Value and growth aren’t mutually exclusive. As Warren Buffett suggests, “Growth is always a component in the calculation of value, constituting a variable whose importance can range from negligible to enormous and whose impact can be negative as well as positive.”

- Technology may have altered fundamental analysis for good but it’s also possible the markets are getting better at taking away easy profit opportunities.

- Value investing has changed shape before and will likely change again. Ben Graham used to invest in net-nets, which were stocks that traded for less than the value of their current assets. Those opportunities basically don’t exist anymore as they did in his day. So it goes.

No one has the answers to all of the questions I’ve brought up here which is why the best approach for me is to avoid thinking or acting in extremes when it comes to my portfolio. There are no rules that say you can’t have competing styles in your portfolio or your factor investing strategy. Relying on a single variable for performance purposes is an unnecessary and avoidable risk. One of the biggest benefits of being diversified is the ability to see the outperforming parts of your portfolio pick up the slack for the underperforming parts.

I don’t know if Amazon killed value investing but it seems like betting heavily, either way, would be a mistake.

Further Reading:

Is the Value Premium Disappearing?

1It’s worth noting that although value has underperformed both growth and the overall market, holding onto this style of investing would’ve still given any investor a much better outcome than sitting in cash for this entire recovery. This is why asset allocation will almost always be more important than security or strategy selection. And almost all of this outperformance has come since 2014. From March 2009 through the end of 2013, growth was +188% vs. +182% for value. Since the start of 2014, it’s been growth +94% vs. value +51%.