Investors have spent a lot of time and energy since the financial crisis in search of non-correlated assets.

Most of their efforts have led to disappointing results, mainly because stocks are up huge since then but also because liquid alt and hedge fund strategies have left much to be desired in terms of performance.

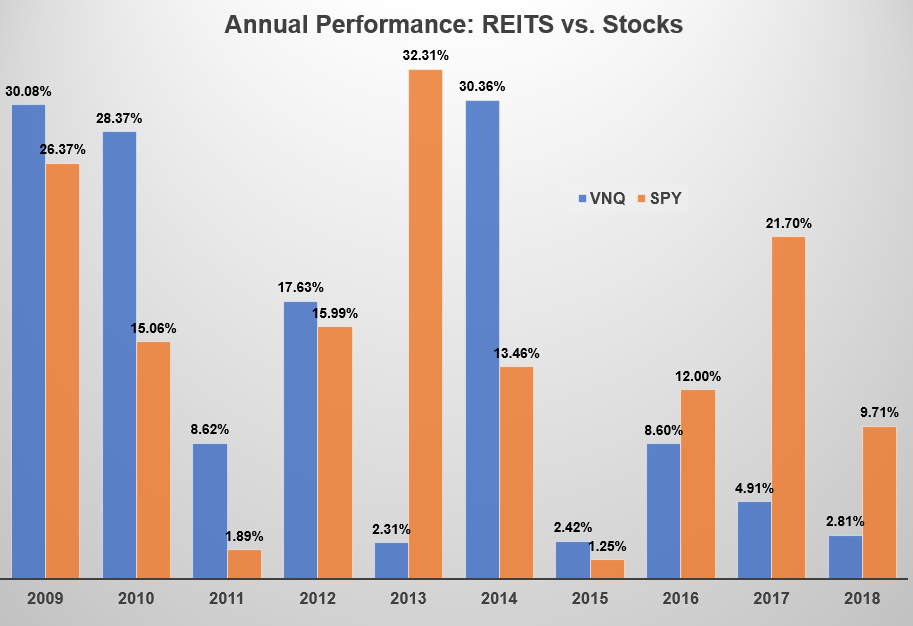

Real estate has actually had a fairly uncorrelated return stream with U.S. stocks since 2009. Here are the annual returns for the Vanguard REIT ETF (VNQ) set against the annual returns for the S&P 500 ETF (SPY) every year since 2009 (through this past week):

The annual returns in this time were 15.1% for stocks and 13.5% for REITs. But the correlation between the annual returns was just 0.20, which is a nice diversification benefit.

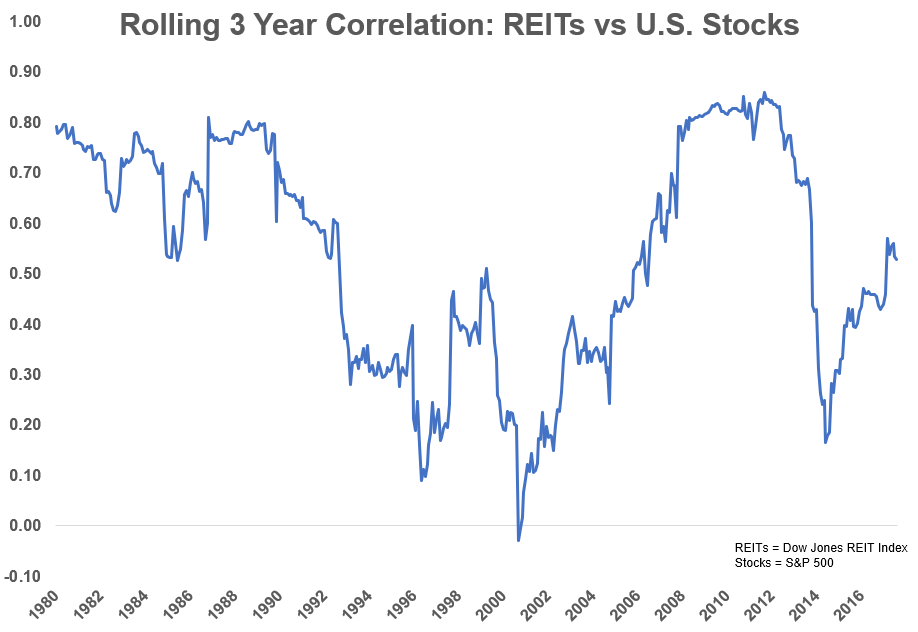

Correlations are far from constant in the markets so it makes sense to look at how these relationships can evolve over time when comparing asset classes. This is the rolling 3-year correlation between the S&P 500 and the Dow Jones REIT Index going back to 1978:

The relationship is far from stable but this is actually a good thing from a portfolio management perspective because correlations are never going to be stable between asset classes. The fact that the correlations can and will change can actually benefit investors from a diversification standpoint.

Any long-term asset class should generally have expected returns above the rate of inflation along with the ability to perform out of lockstep with the other pieces in the portfolio depending on the environment.

From 1978 through July of this year the Dow Jones U.S. REIT Index showed returns of 12.02% with a standard deviation of 18.25%. The S&P 500 saw returns of 11.74% with volatility of 14.77%. But if you were to use a mix of 75% in the S&P 500 and 25% in the REIT index, rebalanced annually, the return would be 12.11% with volatility of 14.18%.

This is not an enormous improvement by any means but combining the two assets saw higher returns than the REIT index and lower volatility than the S&P. That’s the beauty of diversification over the long-term.

There are, of course, caveats when assessing any asset class or strategy:

- REITs have tax implications since, by law, they must pay out 90% of their taxable income in the form of dividends to investors. The new tax laws have made things less onerous from a tax perspective but this should certainly be a consideration when thinking about adding REITs to a portfolio.

- Investors say they want non-correlated assets but what they really want is non-correlated assets that don’t get crushed when stocks fall. REITs aren’t going to offer that type of protection because they are equity-like in terms of risk, volatility, and drawdown profile. If you’re looking for downside protection in real estate because it has higher yields, look elsewhere. From February 2007 through the end of February 2009 the Dow Jones REIT Index fell more than 70%. This tends to happen to risk assets when no one wants to take risk.

- The longest dataset I could find on REITs went back to 1978. Interest rates rose from there until the early-1980s but have been more or less falling ever since. Because yield is such a huge component of returns for REITs, they can be sensitive to changes in interest rates. If there is a sustained rise in rates, REITs could have a difficult time if investors decide there are better yield alternatives elsewhere.

- There’s no handbook that says every investor needs additional exposure to REITs. REITs already make up roughly 4% of the entire U.S. stock market. REITs also make up around 9% of mid cap stocks and 8% of small caps. So if you own a diversified portfolio of funds, you likely already have an allocation to REITs whether you know it or not.

It’s always a good idea to understand how the different asset classes and strategies could potentially help or hurt a portfolio. REITs are a somewhat misunderstood and not very widely followed asset class.

I would venture to guess most investors all but gave up on real estate following the market crash.

The commercial real estate market is roughly the same size as the U.S. stock market. According to MSCI, almost $3 trillion of commercial real estate is professionally managed in the U.S. (worldwide that number is closer to $9 trillion).

So while real estate makes up only a small part of the stock market, it makes up a much larger portion of the overall economy.

Many wealthy investors are enamored with investing in real estate but do so through private means. I’m guessing many of these investors would find REITs offer better diversification, less time and effort, and better returns. The only problem is no one likes to brag about owning a piece of commercial real estate through a mutual fund or ETF.

I’m not sure how REITs will perform in the future because I have no idea what cap rates or interest rates will do from here but it’s always helpful to understand the historical characteristics of the various asset classes to set baseline expectations and a range of outcomes.

Further Reading:

Will Rising Rates Hurt REIT Performance?