The fund I used to work for was invested in an investment manager that performed very well in 2008 when the majority of asset classes and portfolio managers were getting destroyed by the financial crisis and stock market collapse.

This particular strategy was up double digits in a year when stocks fell close to 40%. This fund had billions in AUM but it had been closed to new investors for a number of years (a good sign in my book). Following their good fortune they decided to open things up to new investors because they said they thought they finally had enough capacity to accept more outside money (a bad sign in my book).

And wouldn’t you know it, following a string of outperformance and tons of fresh new capital, they went on to badly underperform in the ensuing 5 year period. Persistent outperformance is nearly impossible, but it’s made harder still when funds get too large to outperform as size is the enemy of alpha.

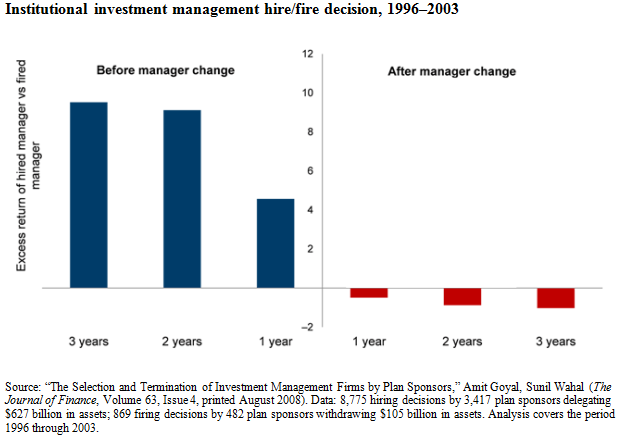

In some ways you can’t even blame this fund for cashing in on their financial crisis success. They struck while the iron was hot. Institutional investors are more than happy to chase performance — to their detriment — again and again. Take a look at this chart from a recent Vanguard blog post on the perils of institutional investors chasing performance:

This chart shows how institutional investment committees continually make their investment manager decisions based on past performance, only to be disappointed by the subsequent returns once they invest. They hired managers that outperformed and fired managers that underperformed only to see those roles reverse after their investment moves were made.

The “smart” money has a nasty habit of buying winning funds after they’ve just won and selling losing funds after they’ve just lost. It’s something of an anti-value, anti-momentum approach where these large funds are always one step behind and fighting the last war.

There are plenty of great portfolio managers out there. But there probably aren’t enough asset allocators or organizations who can discern when to invest with a great portfolio manager and when it’s time to move on. This process is made even more difficult when a large committee has to come together to make group decisions.

It’s not simply that markets are hard. There are many external factors that cause the performance chase to continue. When you manage large sums of money — like a pension, endowment, foundation or family office — there’s never a shortage of funds looking to pitch you. New investment opportunities are seemingly endless. The temptation is always there to make changes to your portfolio. There’s always a new shiny object to draw your attention.

Investment officers and consultants also have to justify the fees they’re being paid. Doing nothing, even when it’s the right thing to do, isn’t easy when others expect to see short-term results. Often times the best thing you can do as a fiduciary is stand between your decision-makers and a huge mistake at the wrong time. Easier said than done during a period of poor relative or absolute performance. Career risk can be deadly to a solid investment plan. Hiring and firing managers is also a nice way to find someone else to blame for poor performance.

A lack of constraints that most individuals deal with also plays a role here. There are little or no taxes paid on the majority of institutional portfolios. The time horizons for many of these funds is technically forever. Plenty of endowments have rich benefactors that continue to make large contributions every year. Take away the constraints of taxes, a defined time horizon and the need for new sources of capital and some of these funds go overboard.

The result can be a huge mismatch between the long time horizon these funds share and the short time horizon used to make investments.

***

Learn more about our institutional practice here.

Source:

The Returns Rollercoaster (Vanguard)

Further Reading:

Consulting & The Smart Money Herd Mentality

I agree with what you wrote, but another reason for why the smart money chases performance that you did not mention is that institutions often employ ‘Window Dressing’ which is where portfolio managers near the quarter or year end invest with a recent outperformer to improve the appearance of their portfolio, before presenting it to clients or shareholders. By buying the great performer after the fact they can imply that they are investing with the best, even if they missed the entire period of outperformance.

It’s insane that this practice still exists, right? Hard to believe investors fall for it but it shows you how little due diligence is performed by many organizations and funds.

Not sure why they call it Smart Money? My personal opinion is to invest for Income, not past performance (or even trying to match market performance). Usually if your stocks continue to increase the income, growth will follow.