The investing cycle of good ideas goes something like this:

Early adopters find an anomaly and exploit it for huge gains. More and more smart money begins to figure out this apparent loophole and competition means lower profits to go around. Next come the academics with their research papers that get published in the trade journals and such. Finally, Wall Street picks up on the trend and does their part to create more products than are needed to help everyone else finally jump in on the fad, usually just as the cycle is about to turn.

John Gabriel at Morningstar wrote a terrific piece last week on commodities, which basically follows this exact pattern:

The holy grail of portfolio diversification: an asset class that provides long-term risk-adjusted returns similar to equities but is negatively correlated with the returns of stocks and bonds. That is what professors Gary Gorton and Geert Rouwenhorst (hereafter G&R) appeared to have identified in their seminal study, “Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures”1.

The paper looked at the period from July 1959 through December 2004 and concluded that the risk premium earned from investing in a broadly diversified basket of fully collateralized commodity futures is very similar to the historical equity risk premium. Moreover, the authors found that the volatility of commodity futures (as measured by standard deviation) was less than that of stocks. According to the study, not only were these superior risk-adjusted returns negatively correlated with stocks and bonds, but they were also positively correlated with unexpected inflation.

This paper coincided with the start of an enormous rally in commodities, which made for a perfect narrative for investors who had been burned by the dot-com crash in stocks. In the markets if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is, as investors in commodities products have figured out in recent years.

Gabriel next goes through a detailed explanation as to why commodities haven’t lived up to their billing as they were described in the research. Depending on the vehicle you’re looking at, a basket of commodities are down anywhere from 40-50% over the past five years. You’ll have to read his entire piece to fully grasp how things have changed in the commodities futures markets, but here’s the kicker:

Over the past 15 years, an allocation to commodities has generally resulted in lower returns and greater risk. Whereas G&R’s influential academic research was based on a period characterized by positive roll yields and high collateral returns, the situation today is much different. Roll yields have turned sharply negative in recent years, and collateral returns are basically nil thanks to near-zero interest rates. Further, rising correlations over the past several years have damped the potential diversification benefits. As a result, barring a return to a persistent state of “normal backwardation,” commodity futures may not be as attractive an asset class as it was once thought to be.

Commodities will almost certainly get to the point where they have an enormous snap-back rally. It’s a boom-bust type of investment. The point here is not to necessarily disparage commodities as an asset class. Some people still like them for their correlation benefits, warts and all. To each their own.

The point is that there are certain times when we see a regime shift in the markets that makes historical numbers irrelevant to a certain extent.

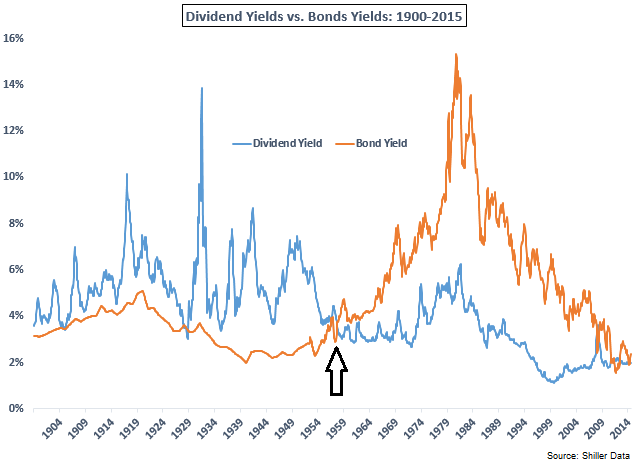

In the early 1900s, stocks used to pay much higher dividend yields than they do today. Part of the reason for this is because they didn’t really buyback their own shares back then. But stocks were not as widely owned as they are today, so to entice equity investors, corporations generally paid out a high dividend yield. In fact, stocks almost always yielded more than bonds. This was such a widely held belief that it turned into something of a market timing signal whenever the two yields would converge.

When dividend yields dropped below bond yields it was time to get out of stocks, after they had risen enough to lower their payout. This worked…until it stopped working. You can see where bond yields crossed stock yields in the late-1950s and never looked back (until recently). Had you continued to use that historical signal and waited to get back into stocks you would have been sitting out for decades and decades.

It’s not enough to look back on history and pick out the strategies that would have worked in the past. Anyone can show you strategies that would have worked brilliantly in the past. That’s the easy part. What matters is looking back at past data and figuring out why something will continue to work in the future (or not work anymore).

That’s where the real money is made in this business.

Source:

Rethinking Commodities (Morningstar)

Further Reading:

Are Commodities For Trading or Investing?

[…] heroes? Even with perfect hindsight hedge funds still disappoint (FT) • When Evidence Fails (Wealth of Common Sense) • Why Twitter’s Dying (And What You Can Learn From It) (Medium) see also Jack Dorsey’s […]

Nice post. Good example of why even very long term trends, which would appear to be good, credible information for portfolio construction, may have nothing at all to do with future performance. Cause and effect can be very, very mysterious.

To summarize, past performance does not guarantee future results. 🙂

As always, when the herd reaches a tipping point of belief or behavior, it may be time to change course. In the post dot-com era, hedge funds were getting a lot of attention and my employer decided to offer a fund of funds to our clients. The reasons given all made sense: low correlation to equities, bond-like yields with lower volatility, etc. Who would not want that? Problem was, every other financial institution jumped on the same band wagon, which ultimately reduced yields (but not costs, surprise! surprise!) and as the 2008-2009 crash revealed, relatively correlations can quickly converge in certain markets. Long-short, the actual benefits of this fund fell short of what had been promised, not because it was a bad idea, but because no investment idea works forever. Unfortunately, this is a concept that is hard to sell to clients who want to believe that everything in their portfolios will succeed all of the time.

Yes. This is exactly why it’s so hard to establish a stable portfolio. I think a lot of people do so by default, at least in their 401K, but also with the sum total of their wealth. No matter how you slice the data, there will be uncertainty, and a lot of people struggle with that.

A site called hardassetsinvestor.com publishes a monthly contango report. Link:

http://tinyurl.com/q2crary

USCI, a fund advised by Geert Rouwenhorst, puts half of its allocation into seven most-backwardated (or least-contangoed) commodities. The other seven are those with greatest trailing 12-month price momentum.

What macro-level asset class investors need is a broad-based contango index. This being the Golden Age of Indexing, doubtless one will emerge soon.

Thanks for another thought provoking post Ben. Why have you stopped mentioning the other stuff you’ve been reading during the week. Please start that again.

[…] When Evidence Fails (awealthofcommonsense) […]

Thanks for the insightful article. A corollary is that economists–especially conjurers of mathematical models– understand much less than they’re presented as knowing.

[…] Wenn der Beweis fehlschlägt (Englisch, awealthofcommonsense) […]

[…] When Evidence Fails “It’s not enough to look back on history and pick out the strategies that would have worked in the past. Anyone can show you strategies that would have worked brilliantly in the past. That’s the easy part. What matters is looking back at past data and figuring out why something will continue to work in the future (or not work anymore).” […]