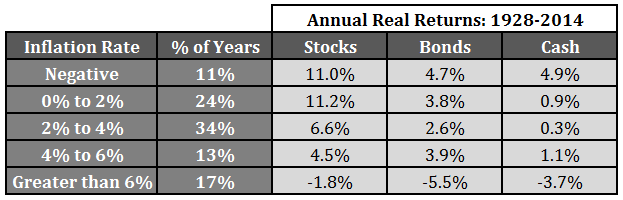

Earlier this week I took a look at how inflation has affected market returns over the years. As you can see from the chart below, inflation has historically run in excess of 4% one out of every three years while it has been 2% or higher two-thirds of the time:

The next logical question — which is one I received from a few different readers — is how to protect your portfolio against inflation. The majority of the usual suspects have been covered here and elsewhere — TIPS, commodities, precious metals equities and real estate to name a few. All of these different investments could protect investors from an inflationary environment, depending on how the cycle plays out.

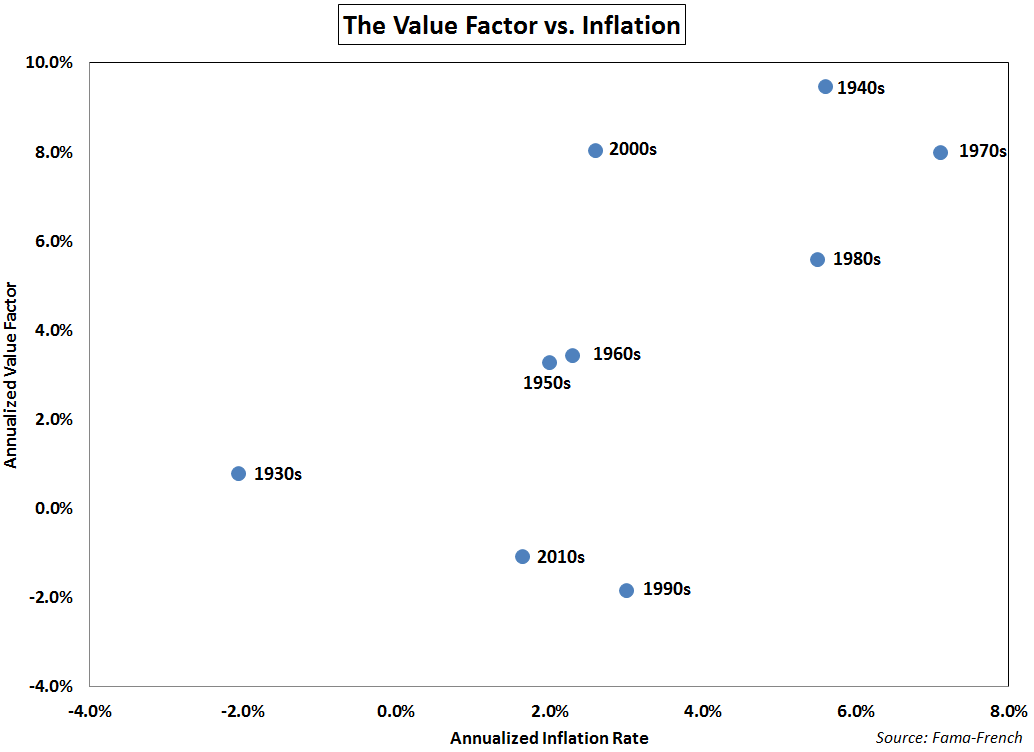

But there are a couple other options that not too many investors think about when trying to plan for an unexpected rise in inflation or rates — value stocks and international stocks. Here is a graph showing the value factor (courtesy of the Fama-French database) over the decades set against the annual inflation rate:

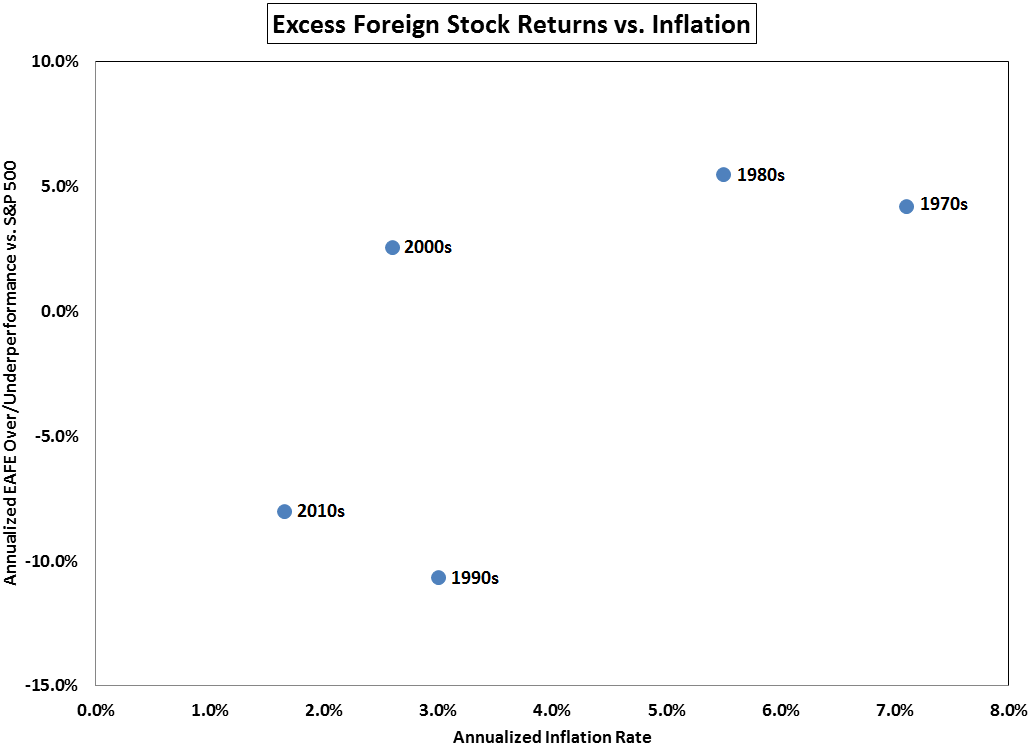

There’s not quite as much historical data, but I ran a similar graph on U.S. (S&P 500) vs. international (MSCI EAFE) stocks, showing the annual over or under-performance by foreign stocks over the decades:

In both graphs you can see the relationship between inflation and outperformance of value and foreign developed market stocks. Higher inflation has tended to result in higher excess returns for both. Growth outperformed value in the 1990s and the current decade right along side of S&P 500 outperformance of the EAFE in lower inflationary times.

The idea for these graphs came from an old William Bernstein post on his Efficient Frontier blog from the early 2000s called Who Killed Value? It was a well-timed post that explained why value had been underperforming growth in the 1990s and why the value premium would eventually come back to life. Here Bernstein explains the reasons for the occasional divergence between value and growth stocks (remember HmL equals cheap minus expensive):

The original Fama-French paper covered a period of very high inflation, the years 1963-1990, and consequently showed a robust value effect. Towards the end of that period, interest rates and inflation commenced a long and powerful decline, which continues to this day—just the sort of environment expected to favor growth stocks. […]

Thus, if inflation stays at 2% to 3%, we can expect an HmL of similar size. And not coincidentally, the HmL for the full 74 years from July 1926 to June 2000 was 3.36%, while inflation was 3.12%. As long as there is fiat currency, there will be inflation; in the long-run, the value premium seems assured.

The most interesting feature of these data is that HmL is much more dependent on the absolute level of inflation than its rate of change. Why, in an efficient market, does a statically high (or low) rate of inflation produce high (or low) HmL? After all, one would assume that a static high or low inflation rate would be discounted into prices. This gets to the heart of the value premium. For if markets are truly efficient, this premium can only be compensation for some sort of risk. An alternative explanation is that markets are not efficient in the value dimension; that in fact, investors overestimate the magnitude and persistence of earnings increases for growth stocks, thereby overpricing them, and underpricing value stocks.

There is obviously a lot more to it than this and there could certainly be some correlation vs. causation issues going on here, but there is some logic behind this theory.

Investors tend to bid up growth stocks in a low interest rate, low inflation rate world because these times are typically associated with slower economic growth. Growth stocks rule in this part of the cycle because investors crave revenue and earnings growth any way they can get it in a slower moving economic backdrop. The cycle eventually turns when lofty expectations aren’t met. If you add in higher levels of inflation to the mix, it becomes a double whammy of unmet expectations and even lower company earnings numbers on a real basis.

Many investors have decided in recent years that international diversification doesn’t work anymore and value investing is dead because both have underperformed. This mindset ignores the cyclical nature of the markets. I’m not sure if or when inflation will pick up in the future. But I like the idea of structuring a portfolio to take into account a wide range of potential outcomes.

Source:

Who Killed Value? (Efficient Frontier)

Further Reading:

How Inflation Affects Market Returns

Why Value Investing Works

I think you miss an important point, which is where Bernstein wrote “The most interesting feature of these data is that HmL is much more dependent on the absolute level of inflation than its rate of change.” This means that when inflation is low (like now), one can avoid international stocks, but when it is high, international diversification is superior, and most importantly, you do NOT need to act in advance, since rate of change of inflation is not so important and you can wait to act until the absolute level of inflation is higher. You write “I’m not sure if or when inflation will pick up in the future” but the beauty of Bernstein’s data is that you don’t have to know, you can wait until inflation has already picked up to make the change. His data supports NOT investing in international stocks when inflation is low, like it is now, and waiting until inflation data shows that inflation is higher, which tells you it is time to make a change.

That’s fair. And I think the other piece that ties this all together is how it all affects the USD. When the dollar is rising int’l stocks will likely underperform.

Exactly. To tie it back into inflation, when US inflation is high, the dollar is likely to be weak, boosting the relative performance of international stocks.

One could investigate whether inflation or the dollar index has the better correlation with foreign stocks, and which one leads.

Really interesting post. The first thing that comes to mind though is how would you explain the success of Value stocks in Japan over the last few decades given their lack of inflation during that period? Any idea why Japan would be different?

That’s a really great question. Not something I’ve looked into, but for some reason it seems like Japan is the place to go to find long-term anomolies (basically everyone uses them as an example about why buy and hold doesn’t work). Do you have the numbers on this?

Cliff Asness wrote a paper called “Momentum in Japan: The Exception that Proves the Rule” in 2011 where he finds Value in Japan generated annual returns of 10.5% and a Sharpe Ratio of 0.71 between 1981-2010. If you can get access to that paper it’s worth a read

Thanks I found it. I just wish he would have shown a long-only value strategy as well. The value used in this is the Fama-French long/short version where you go long the top 30% of cheap stocks and short the bottom 30% of expensive stocks. But it is very interesting to see that value in Japan crushed the results seen everywhere else.

Understood. There is a long only MSCI Japan Value Index if you’re interested. Link below:

https://www.msci.com/resources/factsheets/index_fact_sheet/msci-japan-value-index.pdf

What do the charts show when the data is not aggregated by decade? The 1990s and 2010s on the value chart hurt the assertion that value does better with high inflation. It would be valuable to see the annual data points.

True looking at the decade-long performance makes these numbers much more generalized. But click through to the Bernstein post. He says that looking at shorter time frames actually makes the correlation higher.

[…] Unexpected Sources of Protection Against Inflation (awealthofcommonsense) […]

Producing alpha through investment in the value universe depends on the time of year that value exposure is put into play, and the reduction of equity exposure via the identification of high risk years. Study of investment process spanning 30 years ( here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1XxnEl6aAsU56Afkp_lXAKb8xGWq65wiY8iw3RGTtyuU/edit?usp=sharing ) covers performance during varying periods of inflation with the process’s returns and alpha premia being uniform throughout.

Good stuff. Thanks

[…] Inflation protection and stocks https://awealthofcommonsense.com/protection-against-rising-rates-inflation/ […]

[…] Inflation protection and stocks https://awealthofcommonsense.com/protection-against-rising-rates-inflation/ […]