Fusion’s Felix Salmon got the dreaded pundit call-out this week for making a video telling people to sell their stocks in the after-math of the flash crash in 2010, as seen here:

He was kind enough to pen a response for getting this call wrong, but I still think Salmon has the wrong idea when taking volatility into account with asset allocation decisions:

When volatility spikes, it makes sense to scale back your stocks, and when volatility is low, as it is now, then you can have a riskier asset allocation with more stocks in it. My main error was that I looked at a market-structure artifact, the flash crash, and saw volatility, rather than a one-off event.

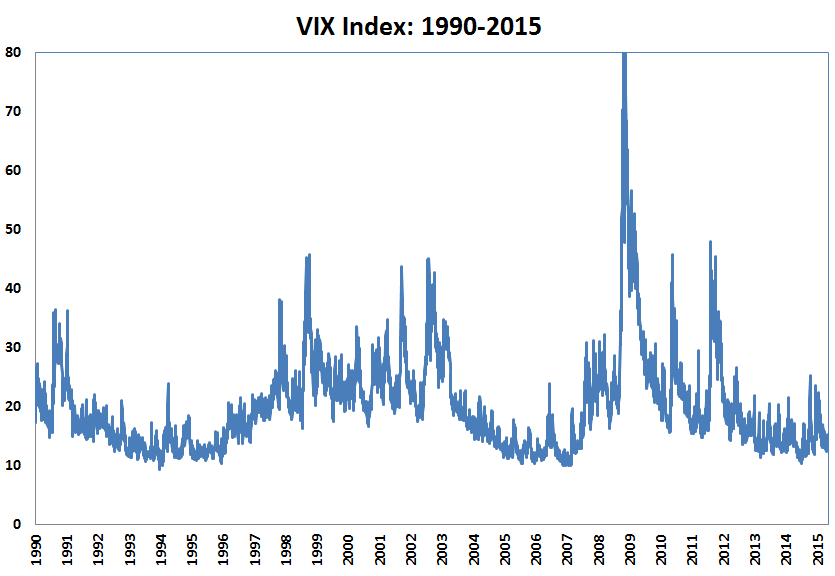

The problem is that it’s fairly difficult to know ahead of time if you’re taking your stock market allocation up or down based on a one-off event or the next major market melt-down. One of the most well-known market volatility indicators is the VIX, which you can see here:

Your timing on these spikes mattered a great deal if you were trying to time game volatilty as some made for great buying opportunities while others could have been great selling opportunities. The majority of the time if you were to wait for volatility to subside you missed your opportunity to buy in at lower prices.

One of the other most cited measures of volatility in the finance industry is standard deviation, which is simply the variation of results around the average. Ken Fisher shared some great stats on the monthly standard deviation of returns in his book The Little Book of Market Myths. For instance, 1932 was the most volatile year ever, with a standard deviation of 65.4%, but stocks fell just -8.9%. The next year volatility was again way above average, 53.9% to be exact, but stocks rose almost 54%.

Volatility was below average at 9.0% in 1977, but stocks were down -7.4%. In 2005, standard deviation was just 7.6%, but stocks were up 4.9%. In 1998 volatility was elevated at 20.6%, yet stocks rose 28.6%. Even when volatility is close to its long-term median (12% to 14%), it doesn’t tell you much. In 1973 stocks fell -14.8% with a standard deviation of 13.7%. In 1951, volatility was 12.1% but stocks were up 24.6%.

All of which is to say volatility does a great job of telling you what’s already happened but not what’s going to happen. At times, increased volatility is a sign of more to come. Other times it’s a one-off event. Successful investing is often counter-intuitive. Usually the best results will come in times when you’re investing during periods of increased volatility. One person’s risk is another’s opportunity.

Following the crash, individual and professional investors alike decided it was necessary to focus their strategy on minimizing volatility and drawdowns. The ironic part about this de-risking is that the market would have taken care of it for them over the following five or six years. Volatility has fell off a cliff during the recovery.

But even more important than trying to pile in when volatility strikes is to be able to come up with a plan of attack for how to handle it regardless of the outcome. Volatility is not a form of risk unless you make it one through your actions and reactions to market movements.

Sources:

The Little Book of Market Myths

I told you to sell your stocks, and then stocks went up. Was I wrong? (Fusion)

Further Reading:

Why Does the Cycle of Fear and Greed Persist

Subscribe to receive email updates and my quarterly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Felix has a huge misunderstanding about portfolio theory.

In MPT your allocation should be based on expected (aka future) volatility, not recent volatility. Since volatility spikes in down markets his advice is analogous to “buy on highs and sell on lows”.

Inferring future volatility is obviously a challenge. Most experts recommend long term historic averages. Some academics might look at option implied vol but I’m not sure if that has predictive power.

Agreed that it’s a buy high, sell low strategy. Your point about future vol is true — not an easy thing to forecast, but I actually think risk is easier to forecast than returns. Instead of always thinking in terms of just volatility, though, you can also frame it in terms of potential losses.

As with everything about the future, you’re shooting for a high probability of success, not precision.

[…] Using volatility to make investing decisions: https://awealthofcommonsense.com/should-you-use-volatility-to-make-asset-allocation-decisions/ […]

[…] On the use of volatility in making asset allocation decisions. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

http://www.wallstreetrant.com/2015/01/doubleline-data-fail-stock-market-has.html?showComment=1431606361532#c8216553714086281780

http://www.wallstreetrant.com/2015/01/doubleline-data-fail-stock-market-has.html?showComment=1431606361532#c8216553714086281780

[…] Volatility: Should You Reduce Investment Allocation When Volatility Rises (Ben Carlson at A Wealth of Common Sense) […]