Interest rate risk has been THE big worry for bond investors for a number of years now. It seems that everyone has been predicting a rise in interest rates, but it just hasn’t happened quite yet.

This has caused many investors to shift their bond allocation in anticipation of a rate increase and price losses in bonds. The problem when making wholesale portfolio changes based on these fears is the timing, as always.

When rates do finally rise bond prices will fall as they’re inversely related to interest rates, but the losses need to be put into perspective. Last year Vanguard performed a study on the effects of an unexpected 3% rise in rates on the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index over five years:

In this example, the initial rise would lead to a steep loss in the near-term (almost 13% in the first year). But as newer bond holdings would get added to the index at the now higher interest rates as older bonds matured the performance would play catch-up. In this scenario, the bond market ends up being positive within 4 years.

Also, it’s worth noting that even under this more than doubling of rates from their current levels, these losses are a fraction of the 50% declines that investors have experienced in stocks over the past two decades. A terrible year in high-quality bonds is a bad week in the stock market.

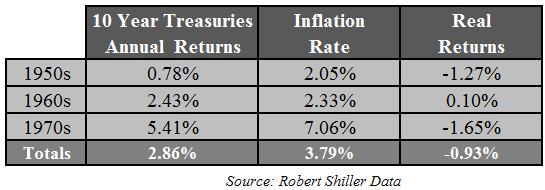

In fact, if you go back to the last period of a sustained rising rate environment from the early 1950s to the early 1980s the annual losses in 10-year treasuries were never really that significant:

Annual losses in the 1950s: -0.30%, -1.34%, -2.26%, -2.10%, -2.65%

Annual losses in the 1960s: -1.58%, -5.01%

Annual losses in the 1970s: -0.78%

The reason there were never any huge losses is that rates slowly crept up over time. In 1950 the 10-year yield was 2.3% while it finished the decade at 4.7%. In the 1960s rates went from 4.7% to 7.8% and by 1980 rates were at 10.8% before finally topping out at 15.3% in 1981.

This slow churn higher until the very end meant that there were never any shocks that led to large drawdowns in bonds.

Yet even with a quick spike higher in yields, as the Vanguard study showed, bond investors can recover from interest rate risk over time. There are a number of other risks to consider when investing in bonds that are potentially more harmful than rising rates.

Inflation Risk: Bond returns weren’t terrible on a nominal basis in the previous rising rate environment referenced above. It was the after-inflation real returns that hurt investors. In fact, from 1950-1981 inflation led to nearly 40% losses in real terms for 10-year treasuries. But it was more of a death by a thousand cuts than a crash like we see in the stock market.

Generally, the longer the holding period for bonds the higher the inflation risk.

Credit Risk: Investors that are chasing yield in lower quality bonds are doing so by increasing their credit or default risk. Higher-yielding fixed income offers those higher yields because the issuers of the bonds have a better chance of defaulting on their debt.

Credit risk doesn’t only concern defaults either. A downgrade in the credit rating of a bond by the credit agencies can affect bond performance as well if institutional investors are forced to sell because of restrictions on the credit quality of the bonds they’re able to hold.

Liquidity Risk: Bonds aren’t as liquid as stocks for trading purposes. This can lead to short-term selling pressure in bond ETFs and mutual funds. There can be a mismatch between the liquidity of the individual holdings and the overall funds.

When everyone heads for the exits all at once it could accelerate the losses in these funds beyond their net asset value. The prescription for this risk is to never be in the position to have to liquidate an entire position just because it’s getting killed in the short-term.

Duration Risk: If interest rates do ever decide to rise, duration will be the most important statistic for bond investors to pay attention to. In the Vanguard study, the 5.5-year duration of the fund meant that for a 1% increase in yields you would expect the price to fall by roughly 5.5%. Longer maturity bonds have higher durations along with higher yields.

The higher the duration of a bond or fund the higher the potential for volatility in both directions when rates move.

It’s worth noting that many of these risks are related. You can’t simply hedge one of these risks without affecting the others. There’s no such thing as ‘all else equal’ in the financial markets as nothing occurs in a vacuum.

We have to consider why interest rates could rise and how each risk factor would be affected. When it happens it will likely be for a number of different reasons including a combination of higher economic growth, higher inflation, lower risk aversion or a pullback in bond purchases by the Fed.

The only thing we can say with any certainty is that bond returns will be much lower going forward than they’ve been since the early 1980s. They have to be because interest rates can only fall so much further and lower yields mean less interest income.

Therefore the biggest risk bond investors face is misaligning expectations with this reality.

Source:

Risk of loss: Should the prospect of rising rates push investors from high-quality bonds? (Vanguard)

I’d say this doesn’t bother me as I don’t invest in bonds. But this will have an effect on the stocks too. Now people are running away from bonds relocating to dividend stocks where they can get better yield now, but when the rates rise and if done slowly they realize the panic was not necessary and we will see outflow from the stocks. All we need to know when is this going to happen and have time to react. Piece of cake.

Good point. It’s also and asset allocation decision. I’ll let you know when I have the specifics on how everyone’s going to react…could be a while.

[…] Looking Beyond Rate Risk […]

I realize many bond investors are willing and anxious to endure losses over a period of 4 years to get back to even…but that’s not me.

In my portfolio, bond must carry their own weight (just like my dividend-paying equities). Therefore, when the 10-yr note’s normalized rate crosses 4.5%, I’ll initiate a small bond position, continue adding as rates advance, and collect the capital gains as rates decline as the cycle next turns.

Impossible to say if/when that’s going to happen but it’s good to know that you have a plan in place instead of simply guessing about the possibility of a rate rise like many others have been doing.

[…] Ben Carlson, “The only thing we can say with any certainty is that bond returns will be much lower going forward than they’ve been since the early 1980s…Therefore the biggest risk bond investors face is misaligning expectations with this reality.” (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

[…] Looking Beyond Interest Rate Risk in Bonds – A Wealth of Common Sense […]

[…] Bonds: Looking beyond interest rate risk – A Wealth of Common Sense […]

[…] Risk. Inflation is the biggest risk to lower interest rates, as I’ve detailed in the past. The historical record of bonds in rising interest rate and highly inflationary environment […]

[…] Reading: What’s an investor to do about bonds? Looking beyond interest rate risk in bonds Back-testing the Tony Robbins All-Weather […]