From 1928 to 2014, stocks earned 4.6% per year more than 10 Year U.S. treasury bonds — 9.6% vs. 5.0%. In finance-speak, this is called the risk premium that stocks earn over bonds.

Academics have tried to explain why the risk premium in stocks exists — they carry more risk, the returns are more erratic and equity owners are at the bottom of the capital structure for repayment. No one really knows the answer. It probably comes down to the fact that equity holders require a higher return on their capital than debt-holders.

Because interest rates around the globe are currently so low (and negative in some cases), many investors have come to the conclusion that stock returns should also be lower in the future. In theory, this makes sense because the long-term returns on bonds will certainly be lower than average based on the current yields. The risk premium is far from stable over time, but it’s reasonable to assume that lower interest rates should lead to lower equity returns.

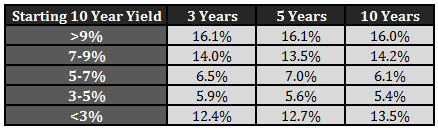

Turning theory into reality can be tricky when you add in the human element of the markets. Let’s test this one out to see if it holds water. I looked back at the starting 10 year treasury yield at the beginning of each year going back to 1928. Next I calculated the subsequent 3, 5, and 10 year annual returns on the S&P 500 and separated each by their initial interest rate level. Here are the results showing the average annual returns for the S&P 500:

Starting with the highest yields at the top and working your way down it appears that the risk premium theory holds. As the starting interest rate deceases the future stock market returns also fall. That is, until you move under the 3% level. At that point average annual returns jump back up again.

I’m not sure exactly why this is the case, but my guess is that most of these low rate periods came after economic crises, so the low yields came about because Fed lowered rates. The returns are above average because they likely came after sharp stock market sell-offs. So even though it doesn’t make sense from a risk premium perspective, it makes sense from a common sense perspective that low interest rates would lead to higher returns based on the timing of those low rates.

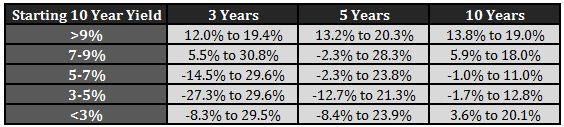

The 10 year yield started out in 2015 at just above 2.1%. Does that mean investors should expect similar above average performance going forward? If it were only that easy. Market averages are never quite as clean as they appear. You always have to consider the range of outcomes that caused the averages you’re looking at. Here are the minimum and maximum annual returns for the averages from above:

By far the narrowest ranges have come from the highest interest rate environments. It’s counterintuitive to invest in stocks when bonds yields are double digits, which is exactly why the returns have been higher from those starting yields. Investors gave up on stocks when interest rates were so high, which pushed down valuations and increased future stock returns.

You can see that once the interest rates were closer to average levels the range of returns were fairly wide for nearly every period, although they do narrow as the time horizon is extended. So while low interest rate environments have led to above average returns in the past, there are always going to be outliers and a wide range of possible outcomes.

As with most historical data, there are scenarios that can work for both bullish and bearish arguments. Stocks have already given investors strong gains from the extended period of low interest rates since the financial crisis, but based on historical performance stocks don’t have to be doomed simply because of low interest rates.

Further Reading:

What the Risk Premium Can Tell Us About Future Returns

Here’s the stuff I’ve been reading this week:

- The only basic financial advice you’ll every need (Prag Cap)

- The surprising investment experts who use index funds (Monevator)

- Benjamin Graham’s greatest gift (The Sova Group)

- Yes stocks will crash eventually, but historically they’re up 20% a year 40% of the time (Irrelevant Investor)

- Is diversification really worth it? (Asset Builder)

- A new kind of investment outlook (Above the Market)

- Most of the research we see isn’t as beautiful as it appears (Research Puzzle)

- Kahneman: “Hindsight induces us to believe we understand the world because we understand the past.” (Think Advisor)

- Everyone is bad at this so work on improving yourself (Fat Pitch)

- It’s impossible to compare investments without considering costs (Malice for All)

- Cry me a river that leads to Omaha (Micheal Santoli)

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Is there a way to couple this insight with Bogle’s method of forecasting stock returns in Common Sense on Mutual Funds? He uses the current & expected PE to add in a valuation component to expected returns.

I haven’t seen that one before. Is it outlined in a paper anywhere? Be happy to take a look.

Gentlemen see my post. I’ve written about a similar model from Research Affiliates:

http://marketfox.org/2014/10/29/what-returns-can-we-expect-from-us-shares-over-the-next-10-years/

The Bogle model is explained in a series of papers from the 1990s. It uses 3 inputs:

1 Current dividend yield

2 Expected earnings growth (Bogle bases his estimate on a historical average)

3 Change in P/E required to get current P/E back to its long-term average

There are links to Bogle’s papers at the bottom of this blog post:

http://marketfox.org/2014/10/29/what-returns-can-we-expect-from-us-shares-over-the-next-10-years/

GMO also uses a similar model.

Nice. Thanks, I’ll take a look.

Part of the difficulty of interpreting your interest rate data set is that it is cyclical data, therefore one data set is not independent of the other, and because rate changes broadly are cyclical, your analysis mixes together when rates are in an uptrend (e.g. 7% going to 9%) with when they were in a downtrend (e.g.. rates going from 9% to 7%). This means that you are incorrectly treating this data as if the interest rate trend direction has no impact on market performance, but the market likely behaves differently depending on whether rates are, over the longer term, going up or going down. I think your analysis would be much more valuable if you separated the same data set into uptrend and downtrend interest data sets, especially since we are in the final stages of a long term downtrend, and will soon(?) enter a long term uptrend. It would be very useful to know how the level AND DIRECTION of rates correlate with market performance and ranges (to indicate volatility).

That’s true but this also assumes that investors can predict the future direction of interest rates and that those trends will continue into the future. Sure you could look as recent trends but those last until they don’t.

[…] What low interest rates mean for the stock market. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

Hi Ben,

Thanks for your work on this article, interesting to see your breakdown of market performance of S&P 500 performance under different interest rate regimes.

I have two suggestions that might make interesting topics for further research:

1. It might be interesting to see if small caps respond differently to large caps.

2. Try categorizing the regimes in the sample using the direction of change (i.e. interest rates rising or falling) rather than the absolute level of interest rates.

Finally It’s interesting to see what implied return models – similar to those used by GMO, Jack Bogle of Vanguard and Research Affiliates – predict for US equity returns.

http://marketfox.org/2014/10/29/what-returns-can-we-expect-from-us-shares-over-the-next-10-years/

Thanks. You’re the second person to suggest looking at the trend in rates. Good point on the small caps, although the data doesn’t go back quite as far it still might be interesting to see. Good stuff.

Alternatively, stay invested in equities regardless of any rate on anything.

That works too. Sometimes the simplest solution is the best one.

[…] a Wealth of Common Sense, some research on subsequent stock returns based upon interest rates in the beginning of the […]

[…] Ben Carlson shows that rising interest rates are consistent with higher stock prices, using the table (below) of average annual returns. I explained the reason for this in 2010, charting the curvilinear relationship between interest rates and stocks. Basically, extremely low rates are associated with intense skepticism about earnings and the economy. The move to normalize rates is positive for stocks. […]

Maybe it’s not so much about the level of rates, but the direction. With short term rates at zero there is only one direction they can go from here.

That’s an excellent observation.

Kind of. From the late 30s to the late 50s rate basically went sideways. Not saying that’s going to happen again but it’s a possibility.

The late 30s had a massive capital destroying event,WWII, that set up for the recovery of the late 40s and 50s. It seems to me future equity returns are more a function of the direction of interest rates, corporate profits and the valuation assigned the profits, than of the starting level of interest rates. Rates are low, corporate profit margins are near record highs and valuations are full…anything more than modest equity returns in the intermediate term will be a challenge. I enjoy reading your posts Ben, please keep up the good work.

Yeah no two periods are ever quite the same. I like to say it’s different every time. It makes sense to me that future returns should be lower from here. Another reason is the fact that there’s so many smart people out there competing for returns with a thorough appreciation of market history. The risk premium could very well be compressed from historical levels.

[…] a $9 Trillion Question (Bloomberg) • What Do Low Interest Rates Mean for Stock Market Returns? (A Wealth of Common Sense) • Tech Leads the Way as Nasdaq Climbs (WSJ) • 25 Ways to Get Smarter About Money Right Now […]

[…] 8) A Wealth of Common Sense : Que signifient les taux bas pour le marché des actions […]

[…] Low Interest Rates: Are They Always Good for Stocks (Ben Carlson at A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

Where you invest matters as much as how much you invest in

the stock market. For the safest investments only choose trusted partners and

stocks to put your hard earned money into. OTC Bully has an amazing range of

affiliates who have been with us for the longest time, helping new traders find

their feet in the stock market. Check our affiliates here http://otcbully.com/affiliates/

This is very interesting. I want to learn more about bonds. Their drab nature cloaks a potential dynamo or the opposite. Most people don’t understand bonds very well, so their potential for harm or benefit is obviously under-appreciated as well. Thanks for your blog. Clear concise and accessible to even the most financially challenged, it seems.

If you’re a glutton for punishment and would like to read up more on bonds take a look at this section of my site that has everything I’ve ever written about bonds:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/category/bonds/

Thanks Ben,

I look forward to reading your articles!

[…] Further Reading: Portfolio Management & Decision Fatigue What Do Low Interest Rates Mean for Stock Market Returns? […]

[…] What Do Low Interest Rates Mean for Stock Market Returns? […]