A reader asks:

I have a fairly large sum of money to invest, but I’m nervous about current stock market levels. What are my options to put this money to work in the markets?

I’ve actually been getting this question or some variation of it from quite a few people for the past few years. There are no easy answers when you have a large sum of money to put to work, but things become even more nerve-wracking after large market gains. People are always worried that they’re going to put their money to work right before the market takes a dive.

The two most common options most people consider are: (1) pick a long-term allocation and put the entire lump sum to work or (2) dollar cost average (DCA) a set amount periodically over a set amount of time. The first makes the most sense from a historical perspective because stocks are up roughly 70-75% of the time a year after you invest. But those probabilities offer little consolation after the S&P 500 has risen every single year since 2009. And DCA is a slow and steady strategy that could force you to miss out on future gains. Both can be psychologically challenging.

There is a third option that not as many people consider — value averaging. Developed by Harvard professor Michael Edleson, value averaging (VA) is a systematic strategy that is a variation on DCA that takes into account market movements for future contributions. Whereas DCA invests a set amount each time, VA seeks to put more money to work when markets have fallen and less when it has risen.

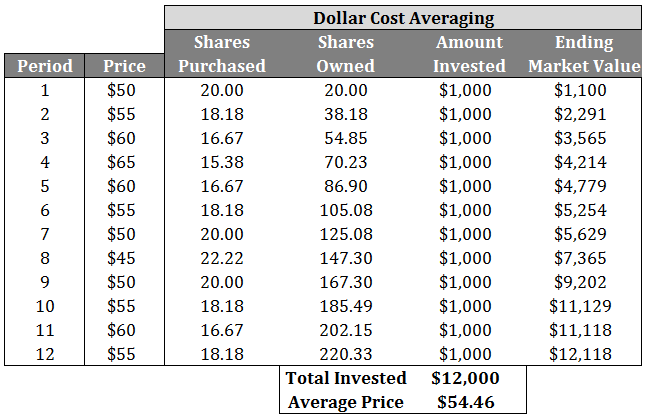

I created a simple example to show the difference between the two. Here is the DCA version with a $1,000 investment made on the first day of each period:

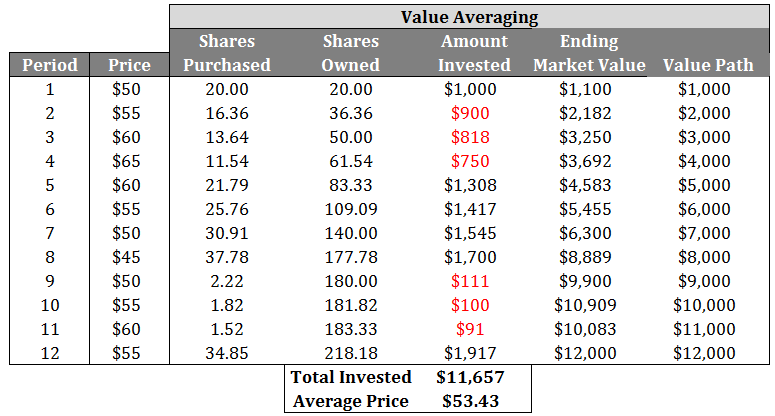

With DCA you buy more shares when markets fall and fewer when they rise, but it’s the same amount invested each time. Now here’s value averaging:

In a VA strategy, you set a certain amount you’d like to hit each period ahead of time, called the value path. If the market pushes your portfolio’s market value higher than your value path, you put less money to work (highlighted in red). With a long enough contribution period, you could even sell some shares to stay on the value path track if markets rise enough (or you could simply hold tight and not put any new money to work). If the market drops your portfolio’s value below the value path, you put more money to work.

In this example, there were fewer total shares purchased in the VA strategy, but you would have bought those shares at a lower average cost. That’s what happens in a rising market. In a down-trending market, you would be investing more money in the VA strategy than the DCA. The hope is this helps assure investors they aren’t completely piling in right before a market peak.

Here’s a quick breakdown of value averaging:

Pros: It’s a formulaic, rules-based strategy. There’s no guessing as long as you set the strategy in advance. The system forces you to put more money to work when markets are falling and less to work when they’re rising, so it’s a disciplined way to force yourself to buy more at lower prices. Edleson has back-tested both strategies back to the 1920s and his work shows VA offers better outcomes the majority of the time when compared to DCA.

Cons: As with all strategies it’s not going to work in all environments. In a hard charging bull market, like the one that we’re currently in, a lump sum investment would turn out to be the better option from a performance perspective. And even though it’s rules-based, it’s difficult to automate. You have to calculate the investment amount every single period you plan to invest. While the calculations are fairly straightforward, inertia and second guessing can set in when you have to force yourself to take action with your savings and investment contributions. If you can’t make yourself follow the plan it’s never going to work.

It’s easy to Monday morning quarterback these types of decisions and you’ll never perfectly stick the landing when making a move with a lump sum of money. It would be great if the markets would just crash very quickly and make it easy for people in this situation to buy in at lower prices, but even that requires courage to act in the face of panic. The point is to have a plan in place that guides your actions instead of making things up as you go.

For those who would like to get a little more advanced than a simple DCA strategy, value averaging is an interesting option. Edleson wrote an entire book on his approach. There’s more than enough information on the historical results in the book if you’re interested in learning more:

Value Averaging: The Safe and Easy Strategy For Higher Investment Returns

Further Reading:

Diversifying Across Time

In 2007, on a non-profit board, we faced the problem of investing a lump sum. Our compromise was to invest 25% at the end of four successive years (2007, 8, 9, 10), while holding the uninvested balance in T-notes that matured when the investment was due to be made.

The 2007 tranche got hit hard. But the 2008 tranche was invested at good prices. The account was reaching new equity highs by 2010.

Faced with the same issue today, with stocks similarly overvalued, I would do exactly the same thing.

I like it. Very simple and spreads out your chances of regret minimization. I’m impressed they/you were able to be so patient. Many funds in that position would put the money to work for fear of benchmark tracking error.

I wish I was that patient… I think?

So few managers and investors have the knowledge, patience, and strength to do something like this. Maybe when the third correction in 15 years happens it will sink in?

Jim, I’m sure you realize you were lucky – investing across the biggest drawdown since the Depression. Most of the time you would be better off investing it all once. I think if I were investing a lump some now, I’d go with the stats and invest it all at once.

Yes, most of the time you WOULD be better off investing it all at once.

However, at the time of our board’s discussions in Summer 2007, Shiller’s CAPE was at 27.40, well into the top decile of historical values (as it is again today).

My claim is that when CAPE is in the top decile, a 4-year averaging process will beat a lump sum commitment. This claim can be tested over the next four years: lump sum invested today, vs. 25% tranches invested in Aug 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018 (and held in T-notes of corresponding maturities until investment).

Good luck! Let’s roll.

Ok, let’s roll! Good luck!!

You would invest everything in stocks right away after a tripling of stock prices in the broader market, a 5-bagger in the Naz, and every historical indication that this market is tremendously overvalued right now?

Yes. I’m agnostic about direction of the market. It is not all together clear that the CAPE is necessarily that high due to a number of factors, and it is not useful for short term market timing. The P/e of the market now is not that high. I think we’re in about the 3rd innings, but I don’t invest that way.

The article written here reminds me of Sylvia Porter’s Money Book…

I’m not familar with that one. Worth a read?

Sylvia Porter was the Suze Orman of the 80’s.

Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

[…] – And here’s the latest from that blog: Investing a lump sum at all-time highs – A Wealth of Common Sense […]

Not trying to be a prophet here, but the markets will experience a 20% correction and then flatline for 5 years until 2020. Secular bull will begin in 2020.

I would wait till mid 2016 for the 20% correction, then DCA till 2020.

Anything’s possible. The big thing the 2020s has going for it will be Millennials hitting peak earnings years so spending, household formation and all that should kick in big time.

I remember running some figures on DCA vs Valuing Averaging under various scenarios a few years ago. The common result I came up with was that VA usually gave a better return rate for the money invested. But what was also apparent was that there was often less money invested under VA and for less long. If you account properly for the opportunity cost of money sitting idly out of the market then VA didn’t really maximise returns of the total ‘money pot’.

As others have noted the strategy that has the highest chance of maximising returns is to lump-sum invest when you have it. DCA should be seen as a risk management strategy. The maximum average future return is sacrificed to reduce the downside of a big early loss which could be wealth damaging and psychologically distressing (losses generally cause more psychological hurt than gains cause psychological pleasure). William Bernstein has an old but very good analysis on his Efficient Frontier Blog – from memory 6 months to a year is the best period to DCA over

That’s the sense I get too. Better IRRs but less money invested. I actually checked this book out on Bernstein’s recommendation from another article so I’ll have to check out his piece. Thanks.

I DCA into a index an only watch CNBC for analyst corrections,sorry I mean aftertiming

[…] Carlsen at A Wealth of Common Sense discusses Value Averaging as an alternative to lump sum […]

Another timely article Ben!

This one made me think of the Level III material that dealt with Constant Proportion Portfolio Insurance rebalancing. Have you ever seen any work on it?

I kind of forgot about that. Never seen any research on it but I’ll take a look. Makes sense

Hey Ben, great article! Can you provide some rationale behind the following though:

“In a hard charging bull market, like the one that we’re currently in, a lump sum investment would turn out to be the better option from a performance perspective.”

Thanks!

Sure, for instance, if you would have simply invested a lump sum a few years ago instead of slowly averaging into the markets you would be better off today with a lump sum over the DCA because markets have mostly risen in that time. There weren’t a ton of opportunities to buy in at lower prices so the environment dictated the outcomes.

Yes, that is in hindsight though and is definitely true for the past few years. But would it be better to invest in lump-sum as opposed to value averaging, given that we don’t know what the future holds? In other words, is it a statistically better approach than VA or DCA?

Here are some past studies for you:

http://www.efficientfrontier.com/ef/997/dca.htm

http://www.businessinsider.com/lump-sum-vs-dollar-cost-averaging-2014-12

This post had awesome timing 🙂

Just goes to show you can never know, eh?

Pure luck. Helps to have a plan of attack because a lot of people probably freaked out yesterday morning.

[…] The pros and cons of investing a lump sum using dollar cost averaging. (awealthofcommonsense) […]