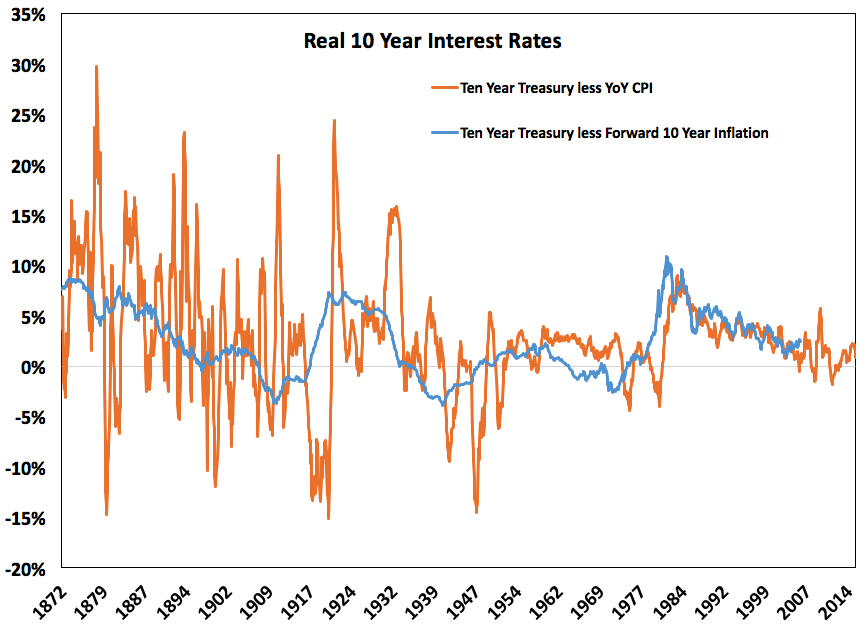

Neil Irwin had a really great write-up at The Upshot this week about the history of interest rates. He made the case that low interest rates may be here to stay if history is any guide. Take a look at the graph he used in the story:

Here’s Irwin with the takeaway:

Very low rates have often persisted for decades upon decades, pretty much whenever inflation is quiescent, as it is now. The interest rate on a 10-year Treasury note was below 4 percent every year from 1876 to 1919, then again from 1924 to 1958. The record is even clearer in Britain, where long-term rates were under 4 percent for nearly a century straight, from 1820 until the onset of World War I.

The real aberration looks like the 7.3 percent average experienced in the United States from 1970 to 2007.

Just eye-balling that chart it would seem to be fairly obvious that Irwin is correct about the historical nature of interest rates. They were low for well over one hundred years, then the period from the 1950s to the 1980s saw a huge spike that was then remedied over the following 30+ years to get us where we are today.

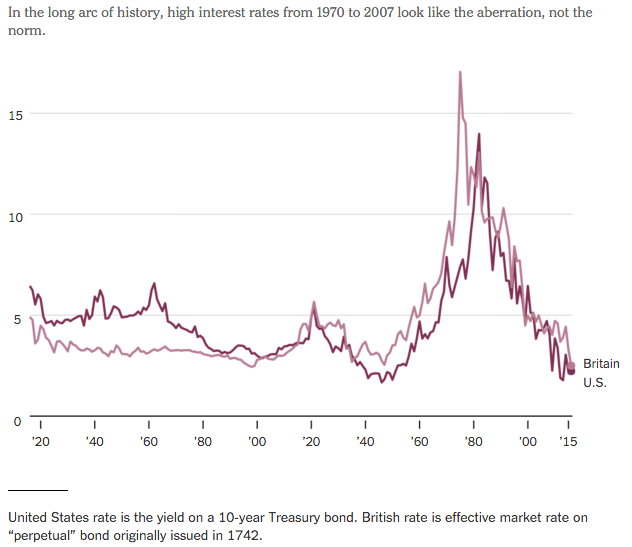

As with most economic indicators, there’s more to the story than this one chart.

While interest rates looked fairly stable during those periods, inflation was anything but. Using historical data from Robert Shiller I calculated the real interest rates on the 10 year Treasury bond over this same period. As you can see, real rates were not quite so stable or low:

The orange line in this chart shows the 10 year Treasury less the annual inflation rate. The blue line tries to take some of the noise out of the year-to-year changes in the CPI and smooth out the data by subtracting the following ten years’ worth of inflation. While the nominal rates have always been positive (save for the current rates in some European countries), the real rates went negative on a number of different occasions because of extreme inflation. And deflationary periods actually led to much higher real rates in some instances as you can see from the spike in the early data.

Real rates in the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century were all over the place. Far from being stable, this was an economic period full of booms and busts. Part of this was because the U.S. was still coming into its own as an economic powerhouse, but a big reason for the wild fluctuations is because we were still on the gold standard.

From 1836-1928 the U.S. averaged a recession every 2.1 years, which included seven depressions that led to an average contraction of 29% in economic activity. People often talk about how the gold standard could help with price stability, but just look at those huge swings on the left side of the chart going back and forth between inflation to deflation.

The huge peak in rates in the early 1980s is also knocked down a peg when you look at them on an inflation-adjusted basis. There’s a reason nominal interest rates were so high back then — inflation was out of control.

It’s impossible to make an exact apples-to-apples comparisons when looking back this far because there are simply far too many variables to control for. Every economic environment and time frame is unique in its own way. But the reason it makes sense to look at the markets using inflation-adjusted data is because it does a much better job of allowing for comparisons across different economic cycles.

It’s certainly possible that interest rates could stay subdued for some time as Irwin alluded to. But rates are only half of the equation here. Inflation will play a large role in determining that path that rates take from here.

Source:

Why Very Low Interest Rates May Stick Around (Upshot)

Further Reading:

Inflation is a Relatively New Phenomenon

Now for the stuff I’ve been reading this week:

- Bonds are usually fine during a rate hike (Bason)

- Reminder: “The stock market is a giant distraction to the business of investing.” (Irrelevant Investor)

- How to be a 21st century dad (FT)

- A house is an asset, not an investment (Abnormal Returns)

- Patrick with a deep dive into the momentum factor (Investor’s Field Guide)

- A Christmas letter from the fund industry (Evidence-Based Investor)

- Financial backtesting: A cautionary tale (Philosophical Economics)

- Using history as a guide for expected stock market returns (Reformed Broker)

- Where have all the sales gone? (Gordian Advisors)

- How to lose money in 2016 (Monevator)