“Unless you can watch your stock holdings decline by 50% without becoming panic-stricken, you should not be in the stock market.” – Warren Buffett

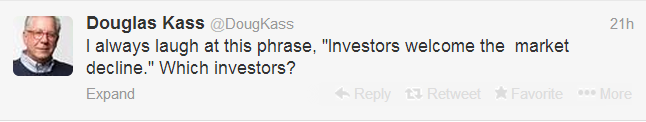

Doug Kass posed a fair question on Twitter this week:

The first thing that popped into my head was ‘younger investors should welcome regular market declines.’

I’ve been working in the investment industry for about a decade at this point. That means I still have multiple decades ahead of me to save and invest. Plus there’s the fact that my biggest asset is not my current portfolio, but my future earnings power.

That means I still have savings to deploy in the market over many years and a long time horizon to grow those savings.

You don’t necessarily have to enjoy market downturns, but you shouldn’t assume they are terrible for your wealth. If you are dollar cost averaging into the market on a periodic basis, losses lower your entry points and increase future returns and dividend yields.

In fact, higher volatility should be welcomed by younger investors because it gives you many more opportunities to buy stocks on sale.

Anyone that is a contrarian or long-term investor has to at least become comfortable with stock losses because they are a part of the market whether we like it or not.

No one likes to see their current stock holdings go down in price because of the fact that losses hurt much more than gains by a rough factor of 2 to 1. Loss aversion has been proven in test after test over the years by Daniel Kahneman.

We also prefer a certain reward today to an uncertain one tomorrow. This risk aversion means it’s difficult for people to trade short-term losses for long-term gains. We all want riskless rewards, even though they don’t exist.

Unfortunately, it usually takes going through several market crashes to build up the correct tolerance and perspective on the wild swings that can occur in stocks.

It takes patience to see your investments through a number of up and down cycles.

This helps explain why experience matters a great deal and more seasoned investors that have lived through multiple cycles are usually more immune to periodic market losses.

Those investors that held off and didn’t sell all of their stocks during the panicked days of late 2008 and early 2009 were rewarded handsomely.

I would imagine most are prepared to handle further disruptions in the future (at least that’s the hope).

Of course, not all investors learn their lessons with stock losses. Just this past week the USA Today ran a story with the headline Big Stock Drops Rock Wall Street.

On Monday the market fell over 1% (not a huge drop by any means). Many individual stocks dropped much more than that, which also happens all the time.

The article went on to give three reasons that the decline in prices made investors nervous:

- The tendency to assume the worst.

- Evidence of investor’s low tolerance for disappointment.

- Investor’s sensitivity to news.

Investors with funds in the market or individual names need to understand it’s a two way street. You can’t participate in the upside and miss the downside. It doesn’t work that way.

Losses are an inevitable aspect of risky markets. It’s also these periodic losses that lead to your biggest opportunities.

One of my favorite Warren Buffett lines was during the terrible bear market of 1973-74 when stocks fell 50% or so. Buffett was asked how he felt about the stock market at the time.

He responded, “Like an oversexed guy in a haram. Now is the time to start investing.”

Here’s further thoughts from Buffett on stock losses:

“If you expect to be a net saver during the next 5 years, should you hope for a higher or lower stock market during that period? Many investors get this one wrong. Even though they are going to be net buyers of stocks for many years to come, they are elated when stock prices rise and depressed when they fall. This reaction makes no sense. Only those who will be sellers of equities in the near future should be happy at seeing stocks rise. Prospective purchasers should much prefer sinking prices.”

It’s a counterintuitive line of thinking but it’s the right way to view the markets if you are building your wealth over decades instead or trying to do it overnight.

(The point here is not to debate Doug Kass on this issue. I understand where he was coming from. I have a great deal of respect for Kass and have been reading his TheStreet.com musings on the markets for a number of years now. His thoughts and analysis before, during and after the financial crisis helped me understand the crash and subsequent recovery in much greater detail. I’m simply using this as a way to share my thoughts on the subject. In fact, if you’re on Twitter, you should follow him for his insights on the markets: @DougKass)

Source:

Big stock drops rock Wall Street (USA Today)

[…] aspects of the investing equation. At the end of the day, most investors worry about losing money. Loss aversion has a powerful hold on our […]

It’s true that lower stock markets are the time to buy–but you don’t want to hold back on the sidelines too long because you can miss a year or more while you wait. That’s why we invest a lot of our money on a steady basis into “capture the entire stock market” funds. While I’m sure we’re paying too much right now, there’s been times when we’ve bought low, too.

But it’s fun to invest some of our “play money” when an unexpected pullback occurs. Last year in Canada Telecomm stocks had a sharp decline when it was believed Verizon might be moving in from the US. I’m quite pleased with the profit we got when we bought on that pullback and watched it bounce back up when the rumour turned out to be untrue. (We’d planned to increase our Telecomm holdings when an opportunity arose; it wasn’t an impulse buy into a stock we didn’t understand.)

Right, I have a similar attitude. For the funds I dollar cost average I just think about where markets will be in 30-40 years and try not to worry about where we stand right now.

We agree on the fun money account as well. That’s where you pick and choose your spots.

[…] Further Reading: The difference between a correction and a crash How I think about stock losses […]

[…] Read More: How I Think About Stock Losses […]

[…] but on designing systems to reduce behavioral biases such as overconfidence, decision fatigue, loss aversion, framing, fear and greed and the recency […]